Prominent security expert Bruce Schneier takes the floor at NZITF to present his book “Liars and Outliers”, providing in-depth analysis of how the concepts of trust and security overlap in the present-day society.

Hey there! What I want to talk about today is trust and security. Basically, what I really want to talk about is the work I’ve been doing the last year that culminated in a book called “Liars and Outliers” which I published about 2 months ago, and the book is really part of my endless series of generalizations trying to figure out how security works and why it exists. Sort of an interesting question to ask: why security exists? You know, we can say security exists because there are bad guys, but, you know, that really doesn’t answer the question. Rocks don’t have security, what is it about people, what is it about life, that requires security? And in the book I attempt to answer that. And throughout the work I came to realize that that the reason we have security is to facilitate trust. The book is about security, trust, and society.

Hey there! What I want to talk about today is trust and security. Basically, what I really want to talk about is the work I’ve been doing the last year that culminated in a book called “Liars and Outliers” which I published about 2 months ago, and the book is really part of my endless series of generalizations trying to figure out how security works and why it exists. Sort of an interesting question to ask: why security exists? You know, we can say security exists because there are bad guys, but, you know, that really doesn’t answer the question. Rocks don’t have security, what is it about people, what is it about life, that requires security? And in the book I attempt to answer that. And throughout the work I came to realize that that the reason we have security is to facilitate trust. The book is about security, trust, and society.

Trust is sort of an interesting concept. This morning I woke up in a hotel trusting quite a number of people who had keys to my room. I went and had breakfast trusting not only the people who cooked the food, I had eggs, but the people who made it, produced it, shipped it. I got into a taxi – another huge trust situation, there are other cars, other drivers, I’m walking down the street, passing people none of whom were attacking me. You may laugh, but if we were a race of chimpanzees, we couldn’t do this. I probably trusted tens, hundreds of thousands people, and it’s 10:30 in the morning and the day hasn’t even started yet.

Our trust is essential to society; now, trust is how society works and we, as a species, are very trusting. We are all sitting in this room, mostly strangers, sure that the person next to us won’t turn and attack us. If this turns out not to be true, society doesn’t function. And the fact that we don’t even think about it – I mean, all the things I’ve just mentioned, it never occurs to us, I’m trusting my food suppliers when I’m cooking dinner tonight – again, the fact that we don’t even think about it, the fact that we can sit here and not worry about the ceiling going to collapse on us, trusting the architects, the designers, the builders, the municipal building codes here in New Zealand, and we trust them to such a degree that it never occurs to us that we are in fact trusting them.

Our trust is essential to society; now, trust is how society works and we, as a species, are very trusting. We are all sitting in this room, mostly strangers, sure that the person next to us won’t turn and attack us. If this turns out not to be true, society doesn’t function. And the fact that we don’t even think about it – I mean, all the things I’ve just mentioned, it never occurs to us, I’m trusting my food suppliers when I’m cooking dinner tonight – again, the fact that we don’t even think about it, the fact that we can sit here and not worry about the ceiling going to collapse on us, trusting the architects, the designers, the builders, the municipal building codes here in New Zealand, and we trust them to such a degree that it never occurs to us that we are in fact trusting them.

So, what I present really is not only a way of thinking about security, but a way of thinking about society and society’s problems. I think the lens of security is a valuable one, and looking at some of the issues in society in terms of security and trust is valuable. So, what I’m writing about and talking about is security’s role in enabling society. There’s a lot written about why trust is important, there’s a whole lot of really good writings, on the values of high-trust societies, the problems of low-trust societies, why it’s important to have trust – I’m not really about that, I’m more of how society enables it.

It’s a good thing that’s given, we are security people, how do we enforce it, how do we make sure that people behave in a trustworthy manner? And it’s also essentially a look at group interest vs. self interest, and how society enforces the group interest, whatever that happens to be.

So trust is a complicated concept. You know, if you work in security, specifically if you write about security, you quickly realize that the word ‘security’ has lots of different meanings, and depending on what you are writing about, the flavor of the word is different.

The word ‘trust’ is even worse. It’s a very overloaded term in our language, it means a lot of different things. There’s a sort of personal intimate trust, when you trust your partner, when you trust a close friend – that’s a very specific kind of trust. It’s interesting, it’s not really about their actions, it’s about who they are as a person. When I say, “I trust my wife”, it’s not because I know she is compliant, it’s because I know her as a person and I trust that her actions, whatever they’ll be, will be informed by that person who I know, and I trust that. I’m trusting their intentions, I’m trusting who they are.

There’s also a much less personal and intimate form of trust. When I say, “I trusted the taxi driver to drive me here”, there’s no intimacy, I don’t know who that driver was, I know nothing about him as a person, I know nothing about his intentions, he could be a burglar on the weekends. I don’t know and I don’t care. I’m trusting his actions within the context of our relationship, which is ‘he’s a taxi driver and I’m a passenger for the 5 minutes that occurred.’ I’m trusting that he won’t run me off the road, drive me north to Auckland, I’m trusting just that piece.

There’s also a much less personal and intimate form of trust. When I say, “I trusted the taxi driver to drive me here”, there’s no intimacy, I don’t know who that driver was, I know nothing about him as a person, I know nothing about his intentions, he could be a burglar on the weekends. I don’t know and I don’t care. I’m trusting his actions within the context of our relationship, which is ‘he’s a taxi driver and I’m a passenger for the 5 minutes that occurred.’ I’m trusting that he won’t run me off the road, drive me north to Auckland, I’m trusting just that piece.

It’s an odd type of trust; I mean, we can, maybe, call it ‘confidence’, I have confidence in what he’s doing, and it’s less that he’s being trustworthy, maybe it’s more that he’s being compliant, but this is the sort of trust that makes the world go round, that is the sort of the trust that we have in the strangers sitting next to us in this room – not who they are, but that they will behave according to social norms which would be sit quietly, don’t make noise, and don’t pick each other’s pockets.

So, when people are trustworthy in that way, the term I use, it’s from game theory, is ‘cooperative’. In today’s society we trust people in this way, but we also trust institutions and systems. It’s not that I trusted the particular front-desk clerk that took my credit card and checked me in yesterday, it’s that I trusted the company that produced him. It’s not that I trusted the taxi driver, but the whole system that produced the taxi driver, the hotel calling the company and the car appearing with the company logo.

And there’s all those trappings that help me trust these strangers, so we trust people, we trust corporations, government institutions, we trust systems. Yesterday I put my credit card into an ATM machine and I got out local currency which I trust is valid, I hadn’t seen it in a couple of decades, and I also trusted, by some magical process I don’t even understand, that a similar amount would be debited from my account back in the United States. I’m not really trusting the bank even, or my bank, I’m just trusting this amorphous international interbank transfer system.

And there’s all those trappings that help me trust these strangers, so we trust people, we trust corporations, government institutions, we trust systems. Yesterday I put my credit card into an ATM machine and I got out local currency which I trust is valid, I hadn’t seen it in a couple of decades, and I also trusted, by some magical process I don’t even understand, that a similar amount would be debited from my account back in the United States. I’m not really trusting the bank even, or my bank, I’m just trusting this amorphous international interbank transfer system.

All complex systems require cooperation. All eco-systems require cooperation. This is true for biological systems, it’s true for social systems, and, important in our world, it’s true for socio-technical systems. They are all fundamentally cooperative. Also, in any cooperative system, there exists an alternative uncooperative strategy – basically, a parasitical strategy. And this holds true for tapeworms in your digestive tract, it holds true for thieves in a market, it holds true for spammers in e-mail, it holds true for companies that take their profits overseas to avoid taxes.

In any cooperative system there’s an uncooperative strategy. And also using game theory, I’m calling those uncooperatives, those parasites ‘defectors’, defectors in the system where we are looking at. These defectors, these parasites, the uncooperatives can only survive if they are not too successful, this is important. If the parasites in your digestive tract get too greedy, you die, and then they die. If the thieves in a marketplace get too greedy, the market closes down, and the thieves starve. Too much spam in your e-mail – we all stop reading e-mail, everyone stops reading spam. If everyone pulls their profits overseas and doesn’t pay taxes, society collapses. There’s this fundamental tension in all systems between cooperating and defecting.

It also can be looked at as a tension between us as individuals and us collectively as society: individuals here, society here. Of course, the individuals and society are the same people, but it’s about how we view ourselves.

Take stealing as an example: we’re each individually better off if we steal each other’s stuff, but we’re all better off if we live in a society where no one steals. We’re each better off if we don’t pay our taxes, but we’re all better off if everyone does. As a country, each of our countries is better off if we do what we want, but the world is better off if countries follow international treaties. That’s that tension. And one other point is we’re all better off if everyone is cooperative and nobody else is, and I’m better off if I’m stealing, but I’m much better off living in the society where no one steals; but I’m even better off, if I’m the only one who’s stealing, because I get the benefit of living in a society where no one steals and I get all your stuff. But of course, if everyone acts that way, society collapses.

Take stealing as an example: we’re each individually better off if we steal each other’s stuff, but we’re all better off if we live in a society where no one steals. We’re each better off if we don’t pay our taxes, but we’re all better off if everyone does. As a country, each of our countries is better off if we do what we want, but the world is better off if countries follow international treaties. That’s that tension. And one other point is we’re all better off if everyone is cooperative and nobody else is, and I’m better off if I’m stealing, but I’m much better off living in the society where no one steals; but I’m even better off, if I’m the only one who’s stealing, because I get the benefit of living in a society where no one steals and I get all your stuff. But of course, if everyone acts that way, society collapses.

Now, most of us realize that it’s our long-term interest not to succumb to our short-term interest and not to steal, or not to pay our taxes, or not to be a greedy tapeworm. But not everyone acts that way, and that’s why we need security. Security is how we keep the number of defectors down to an acceptable minimum, it’s how we induce cooperation, which induces trustworthiness, which, in turn, induces trust. This is the mechanism by which society functions in the face of uncooperative parasites.

Now, most of us realize that it’s our long-term interest not to succumb to our short-term interest and not to steal, or not to pay our taxes, or not to be a greedy tapeworm. But not everyone acts that way, and that’s why we need security. Security is how we keep the number of defectors down to an acceptable minimum, it’s how we induce cooperation, which induces trustworthiness, which, in turn, induces trust. This is the mechanism by which society functions in the face of uncooperative parasites.

So, how does this mechanism work? And that’s really what I’m writing about, because, I think, that’s where it gets interesting. The term I use to describe the measures by which we as society induce cooperation is called ‘societal pressures’ and I like the term because it is a pressure, it’s an inducement, it’s a way not to eliminate defectors, but to minimize them, to keep them down to a manageable level. We are never going to reduce stealing in our society to zero, but it has to be low enough that we all can basically ignore the problem, that we can basically live in a high-trust society, even though there is stealing.

– Morals

– Reputation

– Institutional pressures

– Security systems

And these things can be seen in all societies, actually you can even see them in other primates, you can see other basic aspects of human morality in, actually, some other mammals as well. And so a lot of societal pressure comes from inside our own heads, a lot of cooperation comes from within us. There’s part of it that’s innate, part of it that’s cultural, a lot of it is taught by society about what it means to be a moral member of society, and that’s changed over the centuries – what the social norms are that we should cooperate in, really different now than in a slave-holding society, and they will be different hundreds of years from now. That’s the first, morals.

2 The second is what I call ‘reputation’. In this, again, I mean something very general. By reputation I mean any societal pressure that’s based on what other people do and think. There’s quite a lot of compliance cooperation that we do because we want to be seen by others as a cooperative member of society, as a trusted individual. We, as a social species, rightfully so, put a very high value into what others think about us, and we react to others, we praise for good behavior, we snub for bad behavior, the extreme case of snubbing is ostracism which, in primitive societies, is basically fatal, because as a social species we survive together.And we do a lot of this today. I mean, if a friend steals my sweater, I’m not going to call the police, I’m just not going to invite him over anymore. I will make decisions based on his reputation. Reputation is extremely important to us, there are a lot of great psychological studies on how much people value reputation, what others think, there’s a good theory that language developed as a mechanism for managing reputation. Now, we’re not the only species that uses reputation, lots of other primates will watch each other and make decisions based on what they know about other primates, I mean other people of their species. We are the only species that can transfer reputation information. I can tell you about him, and no one else can do that, it is a fundamental thing language does, it allows us to transfer reputation information.

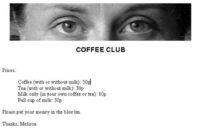

So I can give you one experiment which shows the value of reputation, or it shows how sensitive we are to being watched. This is done in a psychology lab: in the academic department in the university there’s a coffee machine with an honesty box – you get a cup of coffee and you drop a quarter in the box, we’ve all seen these machines. What the researcher found is when he put a photograph of a pair of eyes next to the box – it drastically increased the percentage of people who paid for their coffee. So I mean, even being primed that you might be watched makes people more honest. That’s a really interesting result.

These two societal pressures, morals and reputation, are very old. They are as old as human society. A gossip, the traditional definition of gossip, information about other people, is how we transfer reputation information. And this is, basically, our primitive societal security toolkit. And it works for small societies, works for informal societies, it’s how you and your friends manage trust, it’s how you and your family manages trust, it’s basically how trust is managed in informal groups, or even within companies, within departments. But it doesn’t scale very well, so we invented two more types of societal pressure, we invented laws, and then we use technologies.

3 So laws I call ‘institutional pressures’ because it’s not just legal entities, it’s any formal institution. Any formal institution establishes some sort of formal rules. I mean, think about what these rules are, they are societal norms that are codified, like ‘stealing is illegal’ – we went from ‘stealing is wrong’, which is morals, to ‘if you steal, other people will treat you badly’, to ‘stealing is illegal and there’s a formal punishment process’. We as society delegate some subset of us to enforce the laws, to enforce those social norms. And that’s really where laws came from, they impose formal sanctions. 4 And the 4th mechanism is our security systems. And a security system is basically a mechanism that induces cooperation, prevents defection, induces trust, compels compliance; so you are going to get a door lock, or a tall fence, burglar alarm, guards, forensic and auditing systems, mitigation recovery systems – so a lot here, some of them work before the fact, some after the fact, some during, and they all work together. Go back to stealing. Most of us don’t steal because we know it’s wrong; the rest of us don’t steal because of what other people will think; the rest of us don’t steal because it’s illegal and we’ll get trouble, we’ll get arrested; and for the few people that none of those 3 things have deterred, we lock our doors. We can’t do just one, you have to do all of them, to different degrees, depending on the issue. But what I want you all to go away with is that, as technologist, I think our security toolbox has been woefully inadequate, that we focus quite a lot on the technological systems and very little on the other systems. And it’s important that they all work together.

Go back to stealing. Most of us don’t steal because we know it’s wrong; the rest of us don’t steal because of what other people will think; the rest of us don’t steal because it’s illegal and we’ll get trouble, we’ll get arrested; and for the few people that none of those 3 things have deterred, we lock our doors. We can’t do just one, you have to do all of them, to different degrees, depending on the issue. But what I want you all to go away with is that, as technologist, I think our security toolbox has been woefully inadequate, that we focus quite a lot on the technological systems and very little on the other systems. And it’s important that they all work together.

So think of this as an individual, I mean, there’s a person who is going to make some cooperative defect decision: “Should I steal or should I not?” He’s going to weigh the costs and benefits. These societal pressures are ways for society to put its finger on the scales, for us to change the equation that the person is going to make, it changes the evaluation.

And of course, this depends on context, because a lot of these things are subjective, people will value things in different ways, and that’s why we have defectors even though we have all of these things. We as society use these pressures to find some optimal balance between cooperating and defecting, because more security isn’t always better. If we have too much societal pressure, it gets too expensive. If we have too little societal pressure, it’s too damaging. There are some sweet spots, there’s some murder rate in New Zealand, and it’s not zero. It’s very small, it’s small enough that, you know, pretty much all of us don’t worry about it. But getting it to zero is too expensive. And society has a natural barometer here. If the murder rate gets too high, people start saying: “We need to spend more money on police.” If the murder rate gets too low, people start saying: “Why are we spending lots of money on police? We have other problems we need to solve.”

And depending what the system is, we have a natural level. And that’s also cultural, that’s changed over the centuries, over the millennia. That’s really our tolerance for risk: how much crime in society is enough, how much tax evasion is okay. We’d like it to be zero, but we’ll never get there, because that’s too expensive.

And what societal pressures do is allow society to scale, and scales are a really important concept here. A lot of those primitive systems were good enough for small communities, good enough for primitive societies, good enough for informal ad hoc communities today. But larger communities require more societal pressures, more formalism.

Today we have global systems that need some sort of global laws, or global rules, and global security technologies, and, in some cases, global moralism.

So I think this way of looking at society has some pretty broad explanatory powers, that there’s value in looking at societal issues through this lens. In the book I talk about terrorism, the 2008 global financial crisis, organized crime, Internet crime – sort of a lot of different issues. And you quickly realize that it all gets very complicated very quickly. And the various pressures are interrelated, you can’t make a simple formula of what the right thing to do is, that it’s very situational both who society is, and what the defectors and cooperators are.

And there are a lot of directions to take this research. One of the problems I had writing this book is that very quickly the topic became unbounded. There are so many things you could talk about that you have to put a box around what you’re saying and decide that some things are in the box and out. And the toil of this talk is actually much worse to have that much less time. So here are sort of some of the issues that I do talk about.

And there are a lot of directions to take this research. One of the problems I had writing this book is that very quickly the topic became unbounded. There are so many things you could talk about that you have to put a box around what you’re saying and decide that some things are in the box and out. And the toil of this talk is actually much worse to have that much less time. So here are sort of some of the issues that I do talk about.

I’ve been saying that it’s group interest vs. self interest, but actually that’s really very simplistic. It is often not, often there are several different competing interests in operation at any one time, we are often members of several different groups, and each group will use its own societal pressure to get the individual to comply, to be cooperative within that group.

Let’s take an example of a group being an organized crime syndicate. So in a group of criminals, a criminal organization, being cooperative means sticking up for your fellow criminal, not ratting on him to the police. And being a police informant is being a defector, being a parasite within the criminal community. But in the larger community of society as a whole, cooperating with the police is being cooperative. And the person who rats on his fellow criminals to the police is being a cooperator, and it’s the criminals who are the defectors.

There are a lot of examples about it. A less stark example might be a person who is employed by a corporation, who has to choose between cooperating with the corporation and cooperating with the society, cooperating with one community he’s a part of, or another community he’s a part of. And people are good at this, but it gets very complicated.

There’s a lot of interactions between different societal pressures – how morals interact with reputation, how morality and the law interact. And we see that in the Internet age trying to pass laws against movie and music pirating – the real problem there is that the community has a community norm where sharing music and movies is being cooperative, that’s what you do on the Internet, you share digital files, and a law that goes against that societal norm is very hard to enforce. You see the same dynamic played out in some countries on drug laws, where the social norm is one thing, and the law is exactly the opposite. So that’s sort of how those interact, interactions are interesting.

How each type of societal pressures scales is really interesting. Morals tend to be very close, and this is rightfully so, we’re more morally protective of out intimates, our friends, our communities, our country, people who look like us, people who speak our language, all of humanity. As those circles get bigger, morality tends to fade. There’s an exception, we do have universal human morals, again, unlike any other species. But a lot of morality is in-group vs. out-group, and where you draw that in-group / out-group line will determine how well morals set a pressure scale.

And reputation doesn’t scale very well. The reputational pressures that work in small communities fail in large anonymous cities. Laws also have a different scaling mechanism. In a lot of ways the natural scaling mechanisms of laws determine how big our political units are, can we have a country the size of the United States or the size of the European Union, or are smaller kingdoms the norm, city-states, or even tribes?

How technology helps these scale is also really interesting. We have a lot on the Internet of technological enhanced reputational societal security systems. When you think of eBay feedback, it’s really interesting; it’s fundamentally a reputational-based system. If you as a merchant cheat me, I’ll write something bad about you in public. And it was interesting to watch over the years eBay having to refine that system as people figured out how to cheat it, how to game it. But it’s a reputational system.

We see that in some of the recommender systems. I assume Yelp is here. There are a number of sites on the Internet where you can rate businesses, you can rate restaurants and all sorts of other businesses. I use it pretty regularly. If I’m going to a city, I want to know where to eat dinner, I’ll go to Yelp and look for recommendations, look at reviews. That’s actually spawning an extortion racket. There are people who will go to businesses and say: “Give me a discount or I will bad mouth you on Yelp”.

How technology affects these reputational systems both in allowing them to scale and offering new ways to attack them is really interesting.

The effects of group decision-making – I think, it’s really important here. I’ve been talking about these cooperation defect decisions as made by individuals, but very often it’s groups who make them, and a company decides whether to pay its taxes or not, or to overfish or not. How this plays out within common groups is interesting, within organizations. I have an entire chapter where I talk about how this works within corporations, another chapter about how it works within government institutions.

Back to scale, looking at how this scaling of society gets larger and more complex. Then lastly, what happens when the defectors are in the right? I mentioned the criminal organization issue, and that’s really interesting because being within a criminal organization, being the parasite means being a police informant, that’s what a defector does, but in an abstract moral sense he’s doing the right thing. Think of any type of conscientious defector, civil disobedience. In the United States in the 1800s slavery was ended, as that was happening the abolitionists who helped free the slaves were the defectors, they were breaking the law. Similarly, in the United States, in Europe, the ‘Occupy movement’ are defectors in society.

I don’t have time to sort of just go into all of those complications, although they’re really interesting.

The one I do want to talk about, because I think it matters most to the people in this room, are the effects of technology. Technology gets back to scale, technology allows society to scale, and scale affects societal pressures, it affects it in a bunch of ways: more people, I’ve already mentioned how anonymity affects reputation, but more people affect societal pressures in a lot of different ways increase complexity; more complex systems; new social systems, the fact that Facebook exists and Yelp exists; new security systems, technology will invent security systems.

Increased intensity, this is an odd one – this is basically what I’m trying to say here, that technology allows defectors to do more damage.

Think about my balance again, we have some balance of, I don’t know, banking fraud, some amount of banking fraud that society deems acceptable, we’ve instituted societal pressures to maintain that level. Someone invents Internet banking, the Internet banking criminals realize that there are new ways to commit a fraud – and the balance changes. The same number of bank fraudsters can do more damage because they can automate their crimes on the Internet. That’s what I mean by ‘intensity’. This is the entire debate about terrorism and weapons of mass destruction right here. We as society are worried that the same very few number of terrorists that exist can do much more damage with these modern weapons. Technology increases frequency, it increases distance – you can have the bad actors operating from a longer distance.

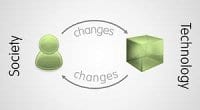

Technology results in the balance changing. We have this balance in cooperation defectors, technology changes it somehow, and society has to respond to restore that balance with some sort of new societal pressures, maybe some new laws, maybe some new technology, maybe some new group norms, maybe some new reputational systems.

Technology results in the balance changing. We have this balance in cooperation defectors, technology changes it somehow, and society has to respond to restore that balance with some sort of new societal pressures, maybe some new laws, maybe some new technology, maybe some new group norms, maybe some new reputational systems.

This is an iterative process, I mean, this is not deterministic, and it is hard to get it right, but, you know, we do more or less, and stability is mostly the norm. The problem here is that attackers tend to have a natural advantage. In these systems, the attacker tends to do better and faster. Some of it is just a first mover advantage, but some of it actually is that the bad guys tend to make use of innovations faster.

Think of someone who invents the automobile, and the police say: “Wow! An automobile!” They have meetings to determine if they need one, they come up with some kind of RFP document, they go out for bids, they evaluate the bids, they buy an automobile, they set up a training program, and they train their officers, and they figure out how they are going to use it. Meanwhile, the bank robber says: “Oh, look, a new getaway vehicle! I can use it instantly.”

We saw the same thing in Internet crime. The possibility of fraud in e-commerce happens on the Net, and pretty much instantly we had a new breed of Internet fraudster that started attacking these systems. Meanwhile, the police who basically trained on Agatha Christie novels had to reinvent themselves, and it took about 7 or so years before the police were able to go after these criminals, and we still have problems because of the scale, the international nature, the inability to collect good evidence.

That’s the delay, and I call that ‘the security gap’, there is a sort of a gap between the good guys and the bad guys, and it’s caused by the delay in restoring the balance after technology imbalances things. And this gap, if you think about it, is, one – greater when there’s more technology; and two – greater in times of rapid technological change, actually, greater in times of greater social change due to rapid technological change. And today we’re living in a society where, one – there’s more technology than ever before; and two – there’s more technological change and resulting social change than ever before, which means the security gap is greater than ever before and, and probably going to remain big for a long time.

I think this is why we’re starting to see in our community different security paradigms that try to take this into account, I’ve seen it called lean security, or agile security, or reactive security; the idea here is that we’re not going to get ahead of the bad guys, we need to be able to respond faster, that’s really about closing the security gap. On the other hand, technology does help societal pressures scale, too.

Technology helps the good guys as well, just not as often and not as much. What are some examples of that in policing: fingerprint technology, the radio. Radio is probably the biggest change in law enforcement ever, because what it did is it no longer was a policeman a lone agent in the community, he could call for backup; that change, you know, happened over a hundred years ago, but the change was remarkable.

What are some examples of scaling? The credit scoring system – I assume, this one is going to be similar here, in New Zealand. In the Unites States there’s a credit scoring system: everybody has a credit score, and it’s a number. And it used to be when you wanted a loan, you would go to the bank, and the bankers would know you, and would give you a loan based on who you were – a reputation-based security system. The problem with that is it doesn’t scale very well, a bank officer has to know you. We’ve replaced that in the United States with a credit scoring system, and you can go virtually, probably online to any bank in the country, apply for a loan, that bank will pull your scoring system, and give you a loan based on that number. And if you think about it, that’s also a reputational-based system, because that number is generated by your past behavior. There is a massive database that has information about you, your income, and your past loans, and your payment history, and makes the decision based on that. It’s probably not as good, but the value of scaling that system is so enormous that it’s worth it.

What are some examples of scaling? The credit scoring system – I assume, this one is going to be similar here, in New Zealand. In the Unites States there’s a credit scoring system: everybody has a credit score, and it’s a number. And it used to be when you wanted a loan, you would go to the bank, and the bankers would know you, and would give you a loan based on who you were – a reputation-based security system. The problem with that is it doesn’t scale very well, a bank officer has to know you. We’ve replaced that in the United States with a credit scoring system, and you can go virtually, probably online to any bank in the country, apply for a loan, that bank will pull your scoring system, and give you a loan based on that number. And if you think about it, that’s also a reputational-based system, because that number is generated by your past behavior. There is a massive database that has information about you, your income, and your past loans, and your payment history, and makes the decision based on that. It’s probably not as good, but the value of scaling that system is so enormous that it’s worth it.

Going back into history, writing allowed moral systems to scale, writing is a technology that allows you to transfer your moral codes, you can write them down in books, and that was a big deal for humanity. All sorts of technologies help laws scale. And of course technologies themselves act as security mechanisms: better door locks, better burglar alarms, better credit scoring algorithms, better fraud detection algorithms for credit cards.

1. Actually, let me do it this way: let me make a bunch of final points and then I’ll take questions. So, I guess this is a sum up. No matter how much societal pressure you deploy, there always will be defectors, and you can never get the defection rate down to zero. The basic reason is, as you get the defection rate lower and lower, the value of switching strategies becomes greater and greater, so somebody will switch.

2. Increasing societal pressure isn’t always worth it. There’s diminishing returns here, if you double the security budget, you don’t get twice the security, so there’s some optimal level.

3. Societal pressures can also prevent cooperation. As you increase the amount of pressure, the greater the chance that you mistakenly punish an innocent. The more draconian you make your anticrime laws, the more non-criminals get caught by accident. And that has an effect on cooperation. A totalitarian state, even one without a lot of street crime, is not considered a high-trust society, because there’s other mistrust that comes out besides.

We all defect in some things at some times, no one is 100% cooperative in all things. We are human and, occasionally, we do put our self-interest ahead of group interest. I’m not convinced this is bad, because there are good defectors and there are bad defectors, and society can’t always tell the difference. Cooperation is about following the social norm. It doesn’t mean the social norm is in some ways moral, there have been a lot of immoral social norms in our civilization’s past, slave-owning is an obvious one, and, presumably, if you fast forward two hundred years there are things that we do in our society that will be looked at as barbaric, primitive, and something no moral society would do any more. Sometimes it takes history to determine who’s in the right.

And this is why society needs defectors. The group actually benefits from the fact that some people don’t follow the social norms, because that’s where you get the incubation for social change, that’s how society progresses.

I’m happy to take questions on sort of any of this, and then after that on sort of greater topics, since I know there’s a lot of things I didn’t talk about.

Q: Thank you! What you are pretty well known for is bringing the issues that we face in computer security outside of computer security. I know you’ve been pushing this message for a long time, do you think that this message has been really picked up globally and that we are, actually, starting to see a transition to seeing computer security in the wider context of an environment and a society?

A: You know, I do think so. Maybe not as formally as I’ve written here, but I think more computer security people are working within their larger context, and that’s because the stuff we’re doing is affecting more and more people, it’s not just securing a bank vault or an Internet website, it’s things like Facebook, where we do have hundreds of millions of people using it, and we have to think more broadly. The people who are doing user interface are looking at how we can trigger different mental processes by our technological mechanisms. So I do see that there’s a couple of conferences that try to put these things together, so I am seeing more of this, I want to see a lot more, because I think we would be much more effective as a community if we understood the greater context and not just looked at the technological aspects of what we’re doing, because as we embed them, I think we get a lot more power and there’s value there. Also, a lot more of our social problems have a technological aspect to them because everything we do these days has a technological aspect, which, again, makes us integrate them more. So, I think, the answer is ‘yes’, but not nearly to the degree that I want.

Q: A lot of what you’ve spoken about has been scaling issues, and you’ve talked also about the positive benefits that come to the enforcers from technology. A lot of those are about security gap being around, institutions not reacting fast enough in your example of the police and the automobile, but we have institutions to do what we can’t do as individuals, and while you speak of the threat of the small number of defectors amplified by technology, isn’t there also a growth in the degree to which we can protect ourselves using those same technologies and, perhaps, in some sense, the institutions will become less significant?

A: I think the opposite is true. That whole, you know, ‘every man’s an island’ – I think it’s total nonsense, especially today. If we sort of think about the global nature of everything we do… You can’t test your own food for poison, you just can’t. You can’t be an expert in your car. I flew here on an airplane, I have no choice but to trust the institutions, the corporations, the systems. So no, I don’t think technology is allowing us to take this into our own hands, more and more we have to trust people, we have to trust people half a planet away that we didn’t 50 years ago, because they are in our supply chains. And as we become more global and more technological, the number of people increases even more, so I think the exact opposite is true.

Q: Thank you for your analysis of the different kinds of defectors, and I was interested by your observation, true observation obviously, that some of today’s heroes were defectors in their times – civil rights movement, for instance. I wonder if there’s some way to tell ex-ante between the defectors who are merely the ones we would still regard as common criminals and those who actually will generate some societal good in the long run.

A: Yes, I think in some cases we can, we have a good intuition about it. We know the bank robber will pretty much never be heralded as the vanguard of the social change of no banks, that just seems implausible; or the mugger; or the person who beats his spouse. And some stuff we know is a little more ambiguous. Are the vegetarians of today going to be the social norm of tomorrow, who knows? I mean this goes really far afield, now we’re nowhere near my expertise, and I’m not even willing to speculate. So there’s a lot of philosophy here that I think is relevant, and again, you know, this is me sort of putting a boundary on what I can talk about.

Q: Is there too much trust in some areas? Some of the bad stuff happens because of the low level of awareness, and people don’t take sufficient precautions to defend themselves.

A: But I think that’s good, in a lot of cases that’s good. There’ll always be some level of bad things happening. It doesn’t mean that society’s better off preventing them. If you are a herd of a hundred thousand gazelles, there’re going to be about two hundred lions circling your herd, picking off the weak ones. It doesn’t mean the gazelles are doing it wrong, it just means there are so many gazelles that this is okay. Of course, the individuals who get eaten are, you know, kind of out of luck, but the value of living in a trusted, in a high-trust society is really great. So we are here and there’s some possibility there’s going to be a pickpocket upstairs, and there are some in New Zealand, and they do make a living. We’re okay, and we’re going to have a fine time at tea; now, we could all take precautions, but we’d have so much less good a time that it’s not worth it. Security’s always a tradeoff, so you have to look at what you’re getting versus what you’re giving up. And I think in a lot of cases humans, we, have a really good trust barometer, we have a good feeling for when we can trust a situation and when we can’t, we get it wrong occasionally, but usually we’re pretty good.

Q: Hi there! Given the massive international nature of a lot of security attacks these days, do you have any comments on how things are working, or changing, improving or not improving internationally as regards enhancing trust for us as a society?

A: International’s hard on Internet systems, there aren’t good international enforcement mechanisms. There are some, and some countries share information, but there always are countries where criminals can operate with relative impunity, and we know where they are, it’s South-East Asia, it’s Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Eastern Europe, parts of South America. I mean, this is where the Internet fraud comes from, because there’s lax computer crime laws, and bribal police forces, and no good extradition treaties.

So I think there are serious issues, and the result is you see a lot of sort of fortress mentality, the institutional systems are failing, so you have to rely more on the technologies, you have to rely more on your firewall. It’s like a low-trust society run by warlords, each warlord maintaining their own security, because you can’t trust the greater society. That’s working pretty well. Internet crime is a huge area of crime, but most of us are on the Net not worrying about it, most of us engage in commerce, most of us do Internet banking, and we do so safely.

It’s hard for us in the industry to remember that we deal with the exceptions, we deal with the few cases, we are the ones who have to worry about the defectors even though they are in a great minority. But in general I think we’re doing okay on the Net, but yes, the international challenges are very hard, we’re doing better, but we’re doing better very slowly. I think it’s going to take a lot to do a lot better because ‘rogue’ countries can do so much damage.

I think the security gap has been getting wider because of more technology and rapid technological change. My guess is those two trends aren’t going to change, which will make the gap get even wider, although I’m heartened by some of the mechanisms that are reacting to this, things like agile security, those sorts of things are a new way of thinking about security that has a potential to close that, and that would be neat to see. I think the jury is still out on whether that will work or not, but at least people are thinking differently, so we have a chance.

Q: Hi! I’m interested in the difference between defectors who defected out of their own self-interest as opposed to defectors who might have been defecting in the interest of a group of people, because I think that might be answering the question of the gentleman at the front, as to who are the ones who might be affecting positive social change.

A: Or defecting because of a higher moral cause, which you can argue is the group interest of a society as a whole. And yes, that is an important distinction to make; I spend a good chapter on that in the book – why someone is defecting matters a lot. And you’re right, that is one way to look at, how you can separate the greedy from the differently moral, for lack of a better term. Although you can claim greed is a moral good, we do have philosophies that try to make that point; then it gets sloppier. But yeah, it does seem obvious that the sociopath and the philosopher are not similar, they are so fundamentally different in their motivations. And you’d think there would be some test to disambiguate them.

Q: You’ve been very outspoken about the US transport security administration as an example of a failed security system, huge overreaction to a minor threat. How can your model of trust and defectors shed light on that, on why that huge reaction has happened and how we can do better in future?

A: Well, I do talk about them in the book, and one of the points I make is it’s really an issue about institutions, and the delegation problem. So we as society delegate (in the United States, it’s the TSA, I don’t know who it is in this country) an organization that will be effectively our proxy to implement societal pressures to deal with whatever this risk is. We among us pick a few of us to go over there and do that. Once we do that, this organization now becomes a separate group, and they have their own group interests, and some of that is maintaining their organization, making sure it gets funded, making sure it looks good. And once you do that you have a separation now between our interests as a society and this group’s interest. And that difference fundamentally causes the problems we’re seeing in things like airport security, and that’s a fundamental problem of the delegation process. In economics this is called the ‘principal-agent problem’: if I hire you to do a job for me, how do I ensure that you’ll do the job for me and not the job for you? But in fact, it’s not really in your interest to do the job for me, it is in your interest to do the job for you, mostly.

That’s the problem. So I do talk about it, it does get really complicated, and that’s the basic flavor of where the answer comes from.

Alright. Thank you very much!