Christopher Soghoian, ACLU’s Principal Technologist, presents his study at Defcon highlighting the past and the present of the privacy and cryptography realm.

Good morning or good afternoon, my name is Chris Soghoian, I am the Principal Technologist for the Speech, Privacy and Technology Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). I started last September, I am the first ever technologist that the ACLU has had who has focused specifically on surveillance and privacy. I finished the Ph.D. last year, specifically focused on the role the Internet and phone companies play in spying on their customers for the government. It’s an extremely timely topic.

Good morning or good afternoon, my name is Chris Soghoian, I am the Principal Technologist for the Speech, Privacy and Technology Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). I started last September, I am the first ever technologist that the ACLU has had who has focused specifically on surveillance and privacy. I finished the Ph.D. last year, specifically focused on the role the Internet and phone companies play in spying on their customers for the government. It’s an extremely timely topic.

I started last September, the ACLU has been very busy in the last year on surveillance issues. Shortly after the Snowden revelations, we were the first organization to file suit against the National Security Agency, although we are not the last. Several other great organizations have also sued the NSA, and hopefully those will keep coming.

Today I am going to be telling a story of how law enforcement and the government have responded to technical change. This will be a story in, I guess, three acts, and really delves into the relationship between the companies and the governments and the different kinds of relationships, because not all companies are the same, some are friendlier than others to the government.

The first crypto wars

So, the first crypto wars – those of you who are a little bit older may remember there was a time when you couldn’t export strong cryptography from the United States. In the mid-90s, then FBI Director Louis Freeh went before Congress on numerous occasions and warned Congress about the threat of encryption: “The widespread use of robust non-key recovery encryption ultimately will devastate our ability to fight crime and to prevent terrorism.” Freeh said this at a congressional hearing in 1997. He added: “Uncrackable encryption will allow drug lords, spies, terrorists and even violent gangs to communicate about their crimes and their conspiracies with impunity.”

In the mid-90s, encryption was a technology that the government sought to demonize, they sought to control the spread of encryption and ultimately to pressure companies to modify their products.

So, Freeh also said: “The only acceptable answer … is … “socially-responsible” encryption products … that … permit timely law enforcement and national security access and decryption pursuant to court order or as otherwise authorized by law.”

The “socially-responsible” crypto that the FBI backed in the mid-90s looked like this (see left-hand image). This is called the Clipper chip. Thankfully, the Clipper chip failed. Professor Matt Blaze found several significant security vulnerabilities in the Clipper chip that meant that it actually wasn’t even good at protecting people from everyone other than the NSA.

So, ultimately the first wave of the crypto wars failed. Congress and the Executive Branch ultimately did away with the crypto export control rules. In 1996 President Clinton signed an executive order reclassifying cryptography and in the years that followed the rules were further relaxed.

Ultimately, companies like PGP were allowed to export their technology around the world. Web browser vendors like Microsoft and Netscape were allowed to export full 128-bit crypto to anyone except people in Cuba and Iran and a couple other countries.

And so, really, the FBI’s initial attempts – and the FBI and the NSA were sort of collaborating there – their initial attempts to control crypto failed. Their previous strategy was: “Let’s stop everyone else other than Americans from getting this stuff. If we make it difficult for them to get the technology, they won’t use it and then we will be able to easily monitor their communications and get their data.”

But even after the crypto export control rules were weakened, and you could download PGP no matter in which country you were, it didn’t actually lead to the widespread use of PGP. Hands up everyone who uses PGP on a daily basis; and for this audience that’s not really that good. I’ll confess I only use it with a handful of colleagues and journalists. Most people who contact me don’t know how to use it. And the reason is PGP is really difficult to use. There is a major important study by Alma Whitten (see left-hand image), who is actually now at Google, ten years ago, pointing out the usability failure of PGP.

Turns out that when a tool is ridiculously difficult to understand how to use, people either don’t use it or they use it wrong. They think they are encrypting when they are not encrypting, which is actually worse because then they will say things that they might not have said if they thought their emails were going through the clear.

And so the widespread availably of encryption really didn’t frustrate the FBI in the way that they though it would – terrorists, pedophiles and drug dealers didn’t suddenly rush out and start using PGP because it turns out that terrorists and pedophiles and drug dealers are like the rest of us. They are lazy and they are not experts at difficult-to-use obscure technology. And so PGP wasn’t the threat that they though it would be.

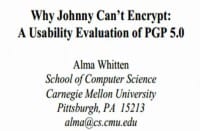

HTTPS, the lock icon that we see in our browsers (see left-hand image), is easier to use because it doesn’t really involve anything from the user side, but even that wasn’t widely deployed. Where SSL was widely used was in e-commerce, online banking. If you were sending your credit card over the web, your communication would be encrypted, but if you were sending your emails, social networking messages, private photos, backing up files, very few of these things would be protected with SSL.

And so, again, the government had a good time, they didn’t have to worry too hard. Although the technologies existed, no one was using them; or at least they were not using them for the things the FBI cared about.

This (see right-hand image) is a slide that the Guardian published lately; it’s from the latest deck that Snowden provided them. This is a deck from XKeyscore, which is the program they have, or the intelligence platform that allows them to monitor vast amounts of communications and then search for it later.

Now, this deck is from 2007-2008, so it’s a little bit old, but you can see clearly, outside of law enforcement and the intelligence space, these folks appreciated that communications were going over the network in the clear. Whether it was Yahoo! or Facebook or Twitter or your emails, they’re easily available for the government to grab with the assistance of their friends at the background Internet providers.

Going Dark

And so, things were good for a while. It didn’t really matter that your browser could do strong crypto. It didn’t really matter that you could download tools from a website and configure them and then have a key signing party, because no one was doing that. But that didn’t stop the FBI from worrying because down the road they saw that things were going to get bad. And it wasn’t going to be because people could download tools, but it was going to be because companies were going to start building crypto into their products by default.

This is Valerie Caproni (see right-hand image), she was until I think a year ago the General Counsel for the FBI, the top FBI lawyer. She’s testified before Congress on numerous occasions. And in 2011 at a congressional hearing, she warned Congress about what the FBI was calling the “Going Dark” problem. “Going Dark” is the FBI’s term for what happens when everyone uses encrypted communications. The FBI has coined this term and spent lots of money researching this issue because they are worried about a day in which all of the communications that users are sending are going to be off limits to the FBI.

This is a quote from 2011: “The FBI and other government agencies are facing a potentially widening gap between our legal authority to intercept electronic communications pursuant to court order and our practical ability to actually intercept those communications.” The FBI says they can get a court order, but when they actually try and get the communications, either the company doesn’t have the capability because they haven’t built wiretapping systems into their networks, or the company cannot provide the data.

She added: “Encryption is a problem. It is a problem we see for certain providers.” And so, what she was describing there was the fact that over a couple of years starting in 2010, companies in Silicon Valley started rolling out SSL encryption by default.

In a Washington Post story, a former FBI official described this to the Post: “Officials say that the challenge was exacerbated in 2010, when Google began end-to-end encryption. That made it more difficult for the FBI to intercept email by serving a court order on the ISP, whose pipes would carry the encrypted traffic.”

In 2010 Google was the first of the big free webmail providers to turn on SSL by default. Google had always offered SSL as an option, but it was an option deep in several layers of configuration screens. I think it was the last of 13 options, after the vacation, auto away message, after Unicode. There was nothing less important in the Google configuration screen than SSL, and so of course no one used it. When the option was hidden and disabled by default, no one’s emails were secure between the user and Google.

But in January 2010 Google flipped the switch and enabled SSL by default. And in the years that followed, several other Silicon Valley companies did the same. It was Twitter, then Microsoft – they renamed Hotmail to Outlook and they turned on SSL at the same time. Facebook started doing it last year, started rolling out, and I think just this week announced that all Facebook communications will be SSL encrypted from the user to Facebook servers.

In addition to that, several companies started rolling out perfect for its secrecy and improved algorithm that makes it much more difficult for government agencies to go to companies and demand private keys. They are upping their key sizes. These Silicon Valley companies are making passive interception much more difficult.

Now, of course that doesn’t mean that the Government can’t get things from Google. Your communications between your computer and Google servers are encrypted, but once the files actually arrive at Google, whether it’s your emails or your private photographs or your instant messages, they are sitting there in plain text.

This is Vint Cerf (see right-hand image), he is Google’s Chief Internet Evangelist; he is also sort of the father of TCP/IP. I was on a panel with him in 2011 in Nairobi. We started talking about Google’s lack of stored encryption. And he said: “We couldn’t run our system if everything in it were encrypted because then we wouldn’t know which ads to show you. This is a system that was designed around a particular business model.”

This is a very honest statement from a Google executive, and I don’t begrudge Google. They offer a fantastic easy-to-use service and they don’t charge people for it. Neither does Twitter, neither does Facebook. These companies all offer one and only one product. There is no way to pay for Facebook, there is no way to pay for Twitter, there is no way to upgrade your Gmail account to a corporate account, a Google Apps account. They have the accounts for users and then the accounts for businesses. And when the only accounts they offer are free ones that are supported by ads, then it makes sense why they are not encrypting your data in the cloud with a key that only you have, because it would be very difficult to monetize that.

Now, what if the companies could, and maybe will at some point, switch to a business model where you give them money and they give you a secure service? That isn’t the business that they are in right now though.

And so, what this means then is that the companies can and do receive requests from law enforcement agencies and intelligence agencies. Even before the PRISM revelations, we have known that Google gets thousands of requests a year from law enforcement and intelligence agencies. This isn’t a surprise.

Silicon Valley vs. telco surveillance

What we have seen in the last few years is a transition. We’ve seen a migration away from telecommunications companies to Silicon Valley companies. In years past, your private messages, your metadata, would be accessible through a backbone provider, through a telephone company, through one of the Ma Bells. And, like it or not, the telephone companies have been providing wiretapping assistance to the U.S. Government for more than a hundred years. The first wiretaps were around 1895 in New York City. For a hundred years these companies have been providing interception assistance to the U.S. Government, and it’s a relationship that everyone is sort of comfortable with, everyone, and by that I mean the companies and the government. And so, these companies don’t just provide targeted access. They don’t just provide access to an individual user’s data; they provide, when the government asks, access to all users’ data.

The assistance of the phone companies is what enables dragnet surveillance. When the government wants to search through every email or search through every phone record, that is only possible because the phone companies provide access to everything.

If you take the Internet companies at their word, the Silicon Valley companies, they only provide targeted access. If the government goes to Google and has a court order with my name on it, Google will hand over my data. But if you take Google at their word, they will not provide access to everyone’s information. And so, what’s happened over the last few years is that consumers have started to migrate their data from the old telecommunications carriers to Silicon Valley companies.

I mean, in many ways the telco’s haven’t had people’s emails for a while – no one is using a Verizon or Comcast email anymore really. But when those email messages were going over the network in the clear it meant the government could still go to the backbone providers. It meant they could go to the AT&T’s and the Verizon’s of the world even if you were using Yahoo! or Google or Hotmail.

But as these Silicon Valley companies have enabled encryption, you can no longer spy on someone’s emails, you can no longer collect bulk information with the assistance of Verizon or AT&T.

I think a great example of this is what Apple did with iOS version 5. In one day they just flipped the switch and suddenly a new version of iMessage was rolled out to users, and if you were an iOS user and you were sending a text message to another iOS user, your messages would go through Apple servers instead of the phone companies. And overnight millions and then billions of messages started flowing through Apple servers, and those were messages that the government cannot get with the assistance of Verizon, AT&T and Sprint.

Now, again, this was a document that was leaked to Declan McCullagh, CNET suggesting that the government can never get messages sent through iMessage. I actually don’t think that is the case. I think that Apple provides access on a targeted basis but I don’t think they are providing wholesale access in the way that the phone companies do.

I think what’s happened here is that there is a difference in culture between the companies. It’s not that Google is trying to make the government go dark. It’s that Google has 350 people doing security and only security. It’s that Apple has a dedicated security team. It’s that Facebook has a dedicated security team. And before you can launch a product at one of these Silicon Valley firms, particularly if it is storing sensitive user data, you have to have crypto. There is no way to secure your users’ data against hackers without crypto.

So, in these companies it’s a corporate policy to encrypt data, not because they want the government to go dark but because that’s what the security teams at the companies demand of them. Realistically, the phone companies don’t have a tradition of security. Your voice mail isn’t secure; you are not getting OS updates to your smartphone if you are using Android, which is by the way something that we have filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission about earlier this year. The phone companies just aren’t interested in security. And so, what’s happening is consumers are giving their data to companies that finally invest some resources in security, and that’s making it tougher for the government.

So, what is the solution? How does the government respond to a world in which they can only get selective data from companies? In some cases they cannot get data at all if the companies are using end-to-end crypto. The answer is backdoors, the answer is compelled access forcing companies to modify their products and provide the government with a way of getting data.

Starting in sort of 2010, we began seeing leaks to the press suggesting that the FBI and others in the law enforcement community were floating these ideas. They were floating legislative proposals expanding CALEA, which is a law mandating backdoors in communications networks and expanding that to Internet companies, to websites and apps and other providers.

We saw sort of these trial balloons floated in 2010 and then ultimately there was a congressional hearing in the spring of 2011 where our friend Valerie Caproni from the FBI testified: “No one should be promising their customers that they will thumb their nose at a U.S. court order…They can promise strong encryption. They just need to figure out how they can provide us plain text, too.”

And this is what the FBI wants, they want the power to go to a company secretly and force the company to quietly insert a backdoor in their own product. As recent as this year, it looked like proposals were coming. It looked like there was a multi-agency working group in Washington, and they were getting ready to drop a bill that would empower the Department of Justice to fine

Silicon Valley companies that refuse to provide the assistance demanded of them.

And then something happened. CALEA 2, which is the D.C. nickname for this backdoor proposal, for now is dead. It is dead in the water, no politician wants to touch that kind of surveillance for now; so thank you very much Edward Snowden.

Government Hacking

Alright, so if they can’t force Google to put a backdoor in Android OS, and if they can’t force Apple to put a backdoor in their software, what are they going to do? How is the Government going to get your communications? What about when they want to listen in to a conversation you are having in your living room, where you are not even using your device? Are they supposed to break in in the middle of the night and install a microphone like they did in the 1970’s? No, they want other ways to access data.

Particularly as consumers have started using services like Skype, and we will talk about Skype later, but services like Skype that have some form of encryption, governments have been having problems, and remember the government isn’t one big beast. The FBI or NSA may have tools to access certain applications but that doesn’t mean they share those toys with local law enforcement agencies. The NSA doesn’t share their secret backdoors with the likes of local cops in Arizona or Nevada. Those folks have to do things the hard way.

It’s also important to note that not all governments are the same. Google has an office, in fact its main office, in California; and Microsoft’s headquarters is in Seattle. Google and Microsoft have to take orders from the U.S. Government. When there is a valid court order, the companies have to provide access to the U.S. Government. But Google doesn’t have an office in Iran. Microsoft doesn’t have an office in Libya, and so if those governments want to get their citizens’ communications, now that Google and Microsoft and others are starting to use SSL, those other governments are really going dark.

In the countries where Google and Facebook and Microsoft don’t have offices and don’t respond to requests, those governments are having a really tough time because of the use of services like Skype, like Twitter, like Facebook. They used to be able to get access through their local, in many cases nationalized telephone company, and now they are going dark, and so those governments are turning to hacking tools too.

What we are seeing is an emergence of the private sector helping companies that are helping governments. The ones that have gotten the most press, the first is a company called Gamma, they make a software suite called FinFisher. FinFisher has gotten a lot of press in the last couple of years starting with a dump of documents by WikiLeaks, and then the excellent work of The Citizen Lab in Canada which exposed the use of this software. They have a really cheesy sales video online that I recommend you look at, so this is the target using iTunes and then getting a malicious man-in-the-middle to update through iTunes. And then the police officer sitting at the remote operating center can spy on the calls and text messages and emails of the user (see right-hand image).

This is the CEO of Gamma, his name is Martin Muench (see left-hand image). You may not know Martin’s name but you probably know Martin’s work. Before he was in the government surveillance business, Martin created a Linux distribution called BackTrack, which is very popular with this community, and so Martin pivoted from providing open-source security tools to providing closed-source government interception tools.

This is my favorite photo of Martin. He is a German guy, without any shame he sells his software to governments around the world. And one of the things his software can do is to remotely activate webcams without the targets’ knowledge. And you can see that he is concerned about this capability because if you zoom in on his laptop you can see he has a little post-it note over his webcam. He clearly knows what his own software can do.

So, because of the work of the folks at Citizen Lab, we know that Gamma software has been exported to Mexico, Ethiopia. It has been used by seriously oppressive regimes in the Middle East and in South-East Asia (see right-hand image). Now, the company says that it’s used for lawful interception and targeting of terrorists and pedophiles and criminals, but from what we know it has been frequently used to target journalists and human rights activists and dissidents. And so, Gamma is one of these companies providing off-the-shelf tools to governments. The police don’t have the resources to develop this stuff in-house, so they just buy this off-the-shelf spyware from companies like Gamma.

Through the last couple of years newspapers have covered this, The Times and Bloomberg have described the spread of this stuff. And the sale of this technology is really unregulated, basically any governments, except for the ones on international blacklists, can buy it.

The other big company is a company called Hacking Team. They’re an Italian company, they make something called the Remote Control System, otherwise known as Da Vinci (see left-hand image). They have a sales video, too, that appears to be targeted to 13-year-old boys. Their marketing stuff says: “Defeat encryption. Total control over your targets. Log everything you need. Thousands of encrypted communications per day guaranteed. Get them, in the clear.” And this software, really, is sold to law enforcement agencies who are trying to deal with things like Skype.

If you are the government of Turkmenistan and there are journalists in your country who are using Skype to communicate, how do you get the contents of their calls when you need them? The phone company in town can’t help, you go to Gamma or Hacking Team and they provide you these tools. This is, again, from Hacking Team’s literature; they say they can get encrypted voice, location, audio and video spying, web browsing activities, relationships. They get anything that is on a computer without the knowledge of the target.

Hacking Team in recent years has expanded into the U.S. market. I believe in the spring of this year they hired this man, his name is Eric (see right-hand photo), he used to be a spokesperson for Verizon and now he is the U.S. counsel for Hacking Team. They have an office in Annapolis, Maryland, just an hour outside of D.C.

We don’t know whether Hacking Team has successfully sold any products to the domestic U.S. law enforcement market, but they are showing up at conferences that are only open to law enforcement and intelligence agencies in Washington, D.C. (see left-hand image). They also went to a conference in Chicago this April, the Law Enforcement Intelligence Units Association (see image below).

Not only did Hacking Team give a talk at this conference – this is a conference targeting local cops around the country – but they also sponsored the coffee break in the afternoon.

And so, if Hacking Team hasn’t sold a product to a local law enforcement agency yet, it’s not because they haven’t been trying. Alright, they have been showing up at these conferences for several years. They are actively targeting the law enforcement market, and I think if they haven’t succeeded already they will succeed soon and get a sale in a small town.

Now, Hacking Team and Gamma Software is the kind of stuff that local cops and governments without too much money use. You know, this is a couple hundred thousand or maybe a million dollars. It’s the kind of thing you buy with a DHS grant. This is not what you use if you are a sophisticated law enforcement agency with big bucks.

What about the Feds?

The feds have the big bucks, federal law enforcement agencies in the United States have enough money to use bespoke custom malware. They don’t need to use the same stuff that the Egyptian and the Turkmenistan governments are using. They can use their own custom spyware and they can buy zero days if they need them.

Again, our friend Valerie Caproni: “There will always be very sophisticated criminals … that are virtually impossible to intercept through traditional means. The government understands that it must develop individually tailored solutions for those sorts of targets.” And when Valerie says “individually tailored solutions”, what she means is hacking. She didn’t use the word “hacking” when she spoke to Congress, but what she means is hacking and malware.

In 2009 or so, I think EFF filed one of their many Freedom of Information Act requests to look into the FBI’s claims that they were going dark. A couple of years later they got hundreds of pages of documents, most of them heavily redacted.

This is one that I found, I read a lot of the documents that groups like EFF produce and documents that the ACLU obtains, and this was one in several hundred pages that the EFF obtained. And most of it was redacted, as you can see (right-hand image), but there was one line that stuck out to me. This is their Remote Operations Unit, so that sounded really interesting, I didn’t really know what the Remote Operations Unit was but it was in a document about going dark. This was a document sort of describing each unit checking in and saying what their progress was. So I thought: “Let me see what else I can find about the Remote Operations Unit.” And so I spent the last six months researching this unit, mainly using open-source intelligence, basically just googling and using LinkedIn. And what I found is that the FBI is in the hacking business too.

So I found the materials for a law enforcement conference that happened in April of this year (see left-hand image). This was a training seminar for prosecutors around the country. And in the list of attendees and speakers at this conference I found information for this guy, Eric Chuang, who is the Unit Chief of the Remote Operations Unit.

I searched a bit more and I found a ZoomInfo page, this is a data mining company that collects information from elsewhere on the web. And Eric Chuang’s ZoomInfo page mentioned that he was the Unit Chief of the Remote Operations Unit, and it said that the Unit “provides lawful computer collection capabilities in support of FBI investigations” (see right-hand image).

Well, that sounded interesting. Then I turned to LinkedIn and I started researching the Remote Operations Unit. What I found is that there are a couple of contracting companies, a couple of contractors who supply people to the ROU. And contractors, like everyone else, want to keep their resume up to date in case they get a new job. So they list things in their resume, maybe things that they shouldn’t be listing, revealing what they did at their old job.

I have not included the names of the low-level contractors but I will be quoting from the LinkedIn pages of several of these contractors because I think what they describe is fascinating. So this (see left-hand image) is a deployment operations analyst at a company called James Bimen Associates, they are a small boutique contracting company in Northern Virginia. So this person “performed testing on … software used as a critical function for counter terrorism and counter intelligence cases.” Okay, that sounds interesting.

He “worked with FBI Case Agents … with our surveillance / imagery software … that is currently installed on criminal subject machines in the field.” Okay, that’s even more interesting. They test “case specific implants against various OS’s and platforms,” – good to know; if you are using Windows or Mac or whatever, they have a tool for you. And then they create “documentation for the … various technologies and methods” that were used to gain access to subject machines.

Alright, so it’s clear from this profile what the Remote Operations Unit is doing. I also found another person, this is a Remote Operations deployment analyst, also at James Bimen Associates. Her profile was fascinating, I thought this was good. She “created policies, guidance and training materials to protect the Deployment Operations tools from being discovered by adversaries,” – those are us. We are the adversaries.

So, Bimen Associates is one of two companies that provide hackers to the FBI. It is my belief and understanding that the contracting companies actually supply the people who sit at the keyboard and are launching the tools. There hasn’t been a debate in Congress about the FBI getting into the hacking business. There hasn’t been any legislation giving them this power, this just sort of happened out of nowhere. And had it not been for the sloppy actions of a few contractors eagerly updating their LinkedIn profiles, we would have never known about this.

The president of James Bimen Associates is a guy named Jerry Menchhoff, he used to work at Booz Allen Hamilton, which is also the same place that Edward Snowden used to work. And so, this is the president of the company, his LinkedIn profile was pretty bare but it did describe one of his interests, and so he is a member of the Metasploit Framework Users Group, thought you guys would get a chuckle out of that.

So I gave Jerry a phone call a few weeks ago and asked him some questions, I of course told him who I was and I said I work for the ACLU, and he wasn’t very nice, he didn’t want to answer any of my questions.

So I gave some of this information to The Wall Street Journal and last night they published a story on this Unit. The nice part about giving these documents to a newspaper is that once they have a bit of information then they can go and report it and get other stuff too.

And so The Wall Street Journal reporter was able to find former law enforcement officials who would be willing to talk on background about this practice. One former law enforcement official she spoke to said: “The bureau can remotely activate the microphones in phones … [and] laptops without the user knowing.” That’s pretty interesting, but she also added: “The [FBI] is loathe to use these tools when investigating hackers, out of fear the suspect will discover and publicize the technique.” So I guess that means that you are all safe from FBI malware.

Meanwhile

The FBI has this team of agents who are doing nothing but delivering malware to the computers of surveillance targets. We only have a couple of cases where these tools have come to light. There was a case in Texas this summer where the FBI sought a search warrant allowing them to target a computer and remotely enable the webcam, collect location data, collect emails.

In this case they went to what you could probably say is the most pro-privacy judge in the country in Texas, and he said “No,” he said they should get a wiretap and they only wanted to get a warrant. What’s clear is that if you have this capability, if you build this team that does nothing but developing malware, the first time you attempt to use the team you don’t go to the most pro-privacy judge in the country.

And so, presumably, they have had this team for a while and they regularly use it to deploy malware.

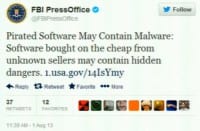

So, on one hand we have the FBI basically being in the hacking business, and then yesterday I noticed that the FBI’s official Twitter account issued a warning saying: “Pirated software may contain malware, beware.” And so I guess we only have to worry about the malware made by other people, not the FBI’s malware.

The next crypto wars

Alright, so the government is using hacking tools, the government is trying to penetrate into people’s computers. They have tried and have up until now been unsuccessful in their attempts to obtain legislation allowing them to force tech companies to put backdoors in their products.

What are they going to do in the future? …Because hacking doesn’t scale. You can break into one person’s computer, you can break into a thousand people’s computers, but you cannot break into a billion computers without getting caught. You can do it temporarily but you will get caught, and the government doesn’t want their tools to get out.

So, what are they going to do in the future? What are they going to do when Silicon Valley companies actually start delivering end-to-end crypto. Not Google, not Facebook, but companies that actually sell services to users.

Well, Microsoft owned one of those companies. For some time Skype was advertising itself as a service that didn’t have backdoors. They were advertising Skype as a service that couldn’t provide access to law enforcement agencies. But we learned last month that the government was able to go to Skype before Microsoft bought them and convince them to modify their products and provide access to the government. Quote from the Guardian story: “[Skype] was served with a directive to comply by the Attorney General.”

Now, we don’t know what kind of directive this was, we don’t know if they went to court, if Skype said “No” and they fought it, or if they did this because they could negotiate some better deal. We really know very little about the ins and outs of how companies can be compelled under existing law. But even so, Skype stopped bragging about their security several years ago. By the time Microsoft bought them all their claims of being wiretap proof had disappeared. Skype was no longer a service, even if it ever was, that advertised itself as the way to securely talk to your friends and family. Instead, Skype was a service that you used to talk to your friends and family to free.

Skype is not the only company offering VoIP services or video. There are now companies that are selling services to users. One of them is a company called Silent Circle, co-founded by Phil Zimmermann, the guy behind PGP. And they charge 10-20 bucks a month for encrypted VoIP and text messages and video. Now, I am not telling you to go and use this company’s services, but they clearly said in their marketing materials: “We have no government-mandated backdoors.” I’ve spoken to the CEO of this company and he said: “If the government comes to us and tries to force us to put a backdoor on our product, we will close up and move to a different country.” The only reason you use their products is for the security. You are not using Silent Circle because it’s crystal clear audio or because it’s cheap and easy to use, you are using them because they are secure.

Likewise, SpiderOak, which is a competitor to Dropbox – you only use SpiderOak and you only pay for their service because they provide encrypted backups with a key only known to the user. And, again, SpiderOak makes clear statements to users: “We’ve created a system that makes it impossible for us to reveal your data to anyone.” That’s it, the only reason you use these companies is to protect your data. And this is the only reason they are in business.

And so the question right now is, and I don’t have the answer to this: can the government force these companies to modify their products? Because if SpiderOak were forced to have a backdoor and it became known – they’d go bankrupt. The only reason you are using them is for the security.

CALEA

There is this law, CALEA, and it’s normally thought of as a bad law; it’s called the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act. CALEA is the law that forces telecommunications companies to put law enforcement interception interfaces into their networks. The reason that AT&T has very easy-to-use and fast wiretapping capabilities is because CALEA forced them to buy a bunch of equipment.

But CALEA has a provision in it that most folks don’t know about. And I am going to read it to you, it’s very short: “A telecommunications carrier shall not be responsible for decrypting, or ensuring the government’s ability to decrypt, any communication encrypted by a subscriber or customer, unless the encryption was provided by the carrier and the carrier possesses the information necessary to decrypt the communication.”

This little feature in CALEA, I think, and I am not a lawyer, is the thing that is standing between these companies and the government. This section of CALEA protects the right of companies that want to offer encrypted end-to-end services, with the key only known to the user, to the general public. And it is my belief that when the next crypto wars come, if they do come, and when they come, that this section of the law will be the thing that the government targets. I think that down the road we are going to see consumers using services that offer end-to-end crypto. I think we will see people paying for these services, and I do think that the government is going to target these, because without it they cannot engage in dragnet surveillance.

Thank you very much!