This entry is based on the Defcon talk “Life Inside a Skinner Box*: Confronting our Future of Automated Law Enforcement” by researchers Lisa Shay, Greg Conti and Woody Hartzog about downsides of automated surveillance and law enforcement.

Lisa Shay: Good afternoon. I’m Lisa Shay, I teach Electrical Engineering at West Point. I’m here with my colleague Greg Conti, who teaches Computer Science at West Point, and our friend Woody Hartzog, who is a lawyer. He’s an assistant professor at the Cumberland School of Law, which is part of Samford University. He’s also an affiliate scholar at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, and he’s worked at the Electronic Privacy Information Center as well.

Lisa Shay: Good afternoon. I’m Lisa Shay, I teach Electrical Engineering at West Point. I’m here with my colleague Greg Conti, who teaches Computer Science at West Point, and our friend Woody Hartzog, who is a lawyer. He’s an assistant professor at the Cumberland School of Law, which is part of Samford University. He’s also an affiliate scholar at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, and he’s worked at the Electronic Privacy Information Center as well.

So, we are going to talk about confronting automated law enforcement, which is any use of automation, computer analysis within the law enforcement process. These are our own ideas, our own thoughts, not those of our employers.

So, we are going to talk about confronting automated law enforcement, which is any use of automation, computer analysis within the law enforcement process. These are our own ideas, our own thoughts, not those of our employers.

The whole idea is: we like living in a free society, and we don’t want to live in a police state.

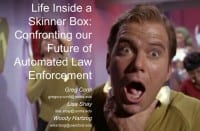

You think about: “It’s always good to obey the law, that’s part of our value system, that’s part of what makes society work.” But think about what happens if everyone obeys every law rigidly all the time. This is a video that many of you have seen where a group of students at Georgia Tech tried an experiment: they drove around the beltway around Atlanta at exactly the speed limit, and they got a bunch of friends together and drove right across the entire highway at exactly the speed limit (see right-hand image). And you can see they’ve got awful traffic jam that’s building up behind them. And the people behind them, you can imagine, were just thrilled to be going exactly the speed limit. It actually could have been a very dangerous experiment: there were people driving on the side of the road to try and get around this.

You think about: “It’s always good to obey the law, that’s part of our value system, that’s part of what makes society work.” But think about what happens if everyone obeys every law rigidly all the time. This is a video that many of you have seen where a group of students at Georgia Tech tried an experiment: they drove around the beltway around Atlanta at exactly the speed limit, and they got a bunch of friends together and drove right across the entire highway at exactly the speed limit (see right-hand image). And you can see they’ve got awful traffic jam that’s building up behind them. And the people behind them, you can imagine, were just thrilled to be going exactly the speed limit. It actually could have been a very dangerous experiment: there were people driving on the side of the road to try and get around this.

So, as I said, automated law enforcement is any computer-based system that is going to use input from unattended sensors that we have all around us to algorithmically determine whether or not a law has been broken and then to take some kind of action. So, really, what we want you to take away from this talk is three things:

1. The networked technologies exist right now.

2. If we aren’t careful in paying attention to how these systems are emplaced, really disastrous consequences could ensue. We could end up living in that police state we showed earlier.

3. You all in this audience are in a unique position to help prevent this. You have the technical knowledge, you have the networks, you’ve got the skills and abilities to see what’s going on and to ask the right questions of people who are trying to implement these systems. So, over to you, Greg.

Greg Conti: So, what leads us to this conclusion? Well, we argue the precursors are in place for this now and it’s a natural extension to what we can see what’s going on now and look into the very near future to see where it’s all heading, and hence to the motivation for our talk to try and generate some interest in deflecting the trajectory of this.

Just imagine the sensors in your home, the sensors on your body, the sensors in your body, the sensors in your car, the sensors in your community; they are proliferating at a massive rate, and that creates data and data flows at enormous amount increasing views on our lives from every angle that can be sampled by a sensor.

Just imagine the sensors in your home, the sensors on your body, the sensors in your body, the sensors in your car, the sensors in your community; they are proliferating at a massive rate, and that creates data and data flows at enormous amount increasing views on our lives from every angle that can be sampled by a sensor.

And we’re seeing increased diversity and sensitivity of sensors. This is an example of someone who had a medical test that injected a radioactive compound into the body for a medical reason: driving home sets off a radioactivity sensor in a police car and gets pulled over (see left-hand image). And this is actually true. But that’s the type of things we’re seeing – the increased diversity of sensors.

And we’re seeing increased diversity and sensitivity of sensors. This is an example of someone who had a medical test that injected a radioactive compound into the body for a medical reason: driving home sets off a radioactivity sensor in a police car and gets pulled over (see left-hand image). And this is actually true. But that’s the type of things we’re seeing – the increased diversity of sensors.

We’re seeing sensors becoming mandatory, as in the United States, this trend toward mandatory black boxes in cars to track. We see increased mobility of sensors (see right-hand image). In the long sight we see the transfer of military technology such as drones into law enforcement roles.

We’re seeing sensors becoming mandatory, as in the United States, this trend toward mandatory black boxes in cars to track. We see increased mobility of sensors (see right-hand image). In the long sight we see the transfer of military technology such as drones into law enforcement roles.

Probably one of the largest areas of concern is the mobile device that we carry on our pocket that discloses our location (see left-hand image). It’s replete with sensors and high-speed network connectivity.

Probably one of the largest areas of concern is the mobile device that we carry on our pocket that discloses our location (see left-hand image). It’s replete with sensors and high-speed network connectivity.

So what I’m trying to paint here is a portrait of where we are now; all these precursors are in place. If you examine them individually – ok, maybe you don’t see so much, but if you put them all together, something larger and more concerning emerges.

The idea of connected cars in OnStar: sometimes you can’t get the car, and particularly in a rental, without it – discloses your location on this full-time connection (see right-hand image). If they can start your car remotely, presumably they can turn it off remotely as well.

The idea of connected cars in OnStar: sometimes you can’t get the car, and particularly in a rental, without it – discloses your location on this full-time connection (see right-hand image). If they can start your car remotely, presumably they can turn it off remotely as well.

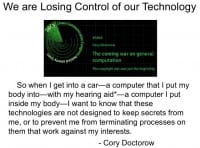

We’re losing control of our technology, and there is a great quote here from Cory Doctorow (left-hand image), but the idea is more and more we’re having closed-source technologies where it’s illegal to lift the lid and look inside the firmware or the software. So, general-purpose computing is under attack, and Cory has a great talk on that; I highly recommend it.

We’re losing control of our technology, and there is a great quote here from Cory Doctorow (left-hand image), but the idea is more and more we’re having closed-source technologies where it’s illegal to lift the lid and look inside the firmware or the software. So, general-purpose computing is under attack, and Cory has a great talk on that; I highly recommend it.

So, we got these data flows. But once you have this data, what’s the key component to identifying the people that are potentially the subjects of this law enforcement system? Obviously, there’re current advances in facial recognition systems.

So, we got these data flows. But once you have this data, what’s the key component to identifying the people that are potentially the subjects of this law enforcement system? Obviously, there’re current advances in facial recognition systems.

In the long sight mandatory biometric databases at the nation state level being constructed, such as in India, where there’s over a billion people being enrolled in such a system.

I think we’ll all admit that facial recognition isn’t there yet, it has its flaws, but hybrid systems are emerging to allow identification of individuals. And this is from identifyrioters.com (see left-hand image). It’s a great time to be alive when there is a website called identifyrioters.com, but this is from the Vancouver riots, where they are trying to solicit crowdsourced

I think we’ll all admit that facial recognition isn’t there yet, it has its flaws, but hybrid systems are emerging to allow identification of individuals. And this is from identifyrioters.com (see left-hand image). It’s a great time to be alive when there is a website called identifyrioters.com, but this is from the Vancouver riots, where they are trying to solicit crowdsourced  identification of people who were allegedly involved in the riots.

identification of people who were allegedly involved in the riots.

There are even business models, like, say, convenience store camera monitoring is being crowdsourced, and then they give small rewards to the citizens. So, what can’t be automated, can be combined in a human-machine hybrid system.

Greg Conti: As we look to the future, has anyone seen Google’s Project Glass video? Even better, have you seen the parodies where they’re wearing the glasses and get text messages while crossing the street and get run over in the crosswalk? You should definitely go to YouTube and look up the parodies that are better than the original. But the bottom line is: if this actually comes to pass, there will be millions of people wearing always-on sensors looking around, every facet of your life on the street being collected. And it’s a matter of then getting access to that data by Corporate America or law enforcement.

Greg Conti: As we look to the future, has anyone seen Google’s Project Glass video? Even better, have you seen the parodies where they’re wearing the glasses and get text messages while crossing the street and get run over in the crosswalk? You should definitely go to YouTube and look up the parodies that are better than the original. But the bottom line is: if this actually comes to pass, there will be millions of people wearing always-on sensors looking around, every facet of your life on the street being collected. And it’s a matter of then getting access to that data by Corporate America or law enforcement.

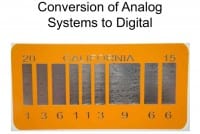

We also see a trend of analog systems being converted to digital systems. Analog systems and analog traditional law enforcement is moderated by the human-in-the-loop intensive nature. But as things become increasingly efficient, then you can have automated law enforcement with unprecedented rigor. And bonus points: what is this license plate from? (See left-hand image) Back to the Future 2, yes. That’s why I love DEFCON, because you know someone will come up with it.

We also see a trend of analog systems being converted to digital systems. Analog systems and analog traditional law enforcement is moderated by the human-in-the-loop intensive nature. But as things become increasingly efficient, then you can have automated law enforcement with unprecedented rigor. And bonus points: what is this license plate from? (See left-hand image) Back to the Future 2, yes. That’s why I love DEFCON, because you know someone will come up with it.

We’re seeing increased capability to analyze these data flows. Here’s a system that claims to be capable of tracking 32 vehicles across 4 lanes (see right-hand image). What we see emerging is, on all major highways, the ability to track every car in real time, identify the car, identify its speed and other activity.

We’re seeing increased capability to analyze these data flows. Here’s a system that claims to be capable of tracking 32 vehicles across 4 lanes (see right-hand image). What we see emerging is, on all major highways, the ability to track every car in real time, identify the car, identify its speed and other activity.

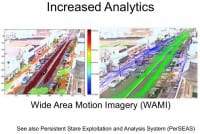

We also see other sensor technologies being developed, such as the Wide Area Motion Imagery system, which can track individual vehicles and people over long term, over the course of hours, long-term monitoring of paths that individual objects, people and cars, are taking (image to the left).

We also see other sensor technologies being developed, such as the Wide Area Motion Imagery system, which can track individual vehicles and people over long term, over the course of hours, long-term monitoring of paths that individual objects, people and cars, are taking (image to the left).

![]() And then, of course, the cost of technology is dropping. Location tracking, where you can track your spouse or children, is dropping on a daily basis, so the technology is getting cheaper and cheaper, where it’s almost disposable.

And then, of course, the cost of technology is dropping. Location tracking, where you can track your spouse or children, is dropping on a daily basis, so the technology is getting cheaper and cheaper, where it’s almost disposable.

Predictive policing – the ability to take the data as it exists that you have now and then try and project that onto the future when and where crimes will occur – is actually reality. We’ve seen this before. Where have we seen it? (See left-hand image) We’re not saying there’s precogs involved, but it’s definitely out there.

Predictive policing – the ability to take the data as it exists that you have now and then try and project that onto the future when and where crimes will occur – is actually reality. We’ve seen this before. Where have we seen it? (See left-hand image) We’re not saying there’s precogs involved, but it’s definitely out there.

And of course, there’s lots of interested parties, because a lot of this comes down to who is incentivized to employ these systems, who is incentivized to constrain these systems. And there’s lots of interest across the law enforcement spectrum and from industry, because there’s benefits to this, and there’s certainly dangers, and there’s certainly financial advantage.

And of course, there’s lots of interested parties, because a lot of this comes down to who is incentivized to employ these systems, who is incentivized to constrain these systems. And there’s lots of interest across the law enforcement spectrum and from industry, because there’s benefits to this, and there’s certainly dangers, and there’s certainly financial advantage.

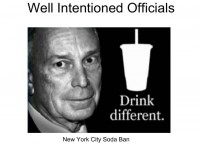

For those of you who live in New York City – and we live in the north of New York – apparently, in the near future we’ll be no longer able to purchase 32-ounce sodas, and that just gives a trend toward the well-intentioned officials that might like the idea of broadly enforcing law across the populace.

For those of you who live in New York City – and we live in the north of New York – apparently, in the near future we’ll be no longer able to purchase 32-ounce sodas, and that just gives a trend toward the well-intentioned officials that might like the idea of broadly enforcing law across the populace.

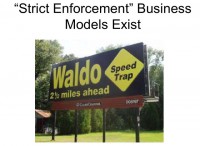

Historically, if you look back, there are certainly law enforcement agencies that have strict enforcement models; some would call them speed traps, such as the Automobile Association of America has erected billboards outside some of these towns to warn motorists (see right-hand image). So there is clearly the opportunity for abuse by automating some of these.

Historically, if you look back, there are certainly law enforcement agencies that have strict enforcement models; some would call them speed traps, such as the Automobile Association of America has erected billboards outside some of these towns to warn motorists (see right-hand image). So there is clearly the opportunity for abuse by automating some of these.

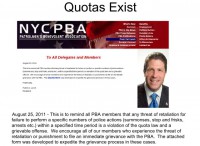

And as to quotas, most law enforcement officials will say: “Quotas don’t exist. We never tell our officers to enforce a quota system and capture to up the numbers for a given month.” Well, we argue that they do, and I’m sure they’re not supported officially. But here is an example that the New York City Police Benevolent Association

And as to quotas, most law enforcement officials will say: “Quotas don’t exist. We never tell our officers to enforce a quota system and capture to up the numbers for a given month.” Well, we argue that they do, and I’m sure they’re not supported officially. But here is an example that the New York City Police Benevolent Association  has actually a report form to report when the officer claims that they’ve been asked to enforce a quota (see left-hand image). These are all trends pushing this forward.

has actually a report form to report when the officer claims that they’ve been asked to enforce a quota (see left-hand image). These are all trends pushing this forward.

Who has seen bait cars? (See right-hand image) They leave a car on the side of the street and someone decides to get in and the keys happen to be in the car and they drive off and they get locked in the car a few blocks away and arrested.  The idea is that these systems can be interacted and used in many innovative ways. And as we look to the future, who knows what type of bait could be used – pleasure model robots (left-hand image), or who knows what?

The idea is that these systems can be interacted and used in many innovative ways. And as we look to the future, who knows what type of bait could be used – pleasure model robots (left-hand image), or who knows what?

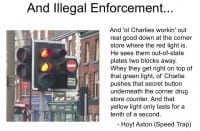

And then, illegal enforcement; we don’t want that to happen. The power that these systems provide allows for illegal enforcement potentially.

And then, illegal enforcement; we don’t want that to happen. The power that these systems provide allows for illegal enforcement potentially.

I want a picture like that on top of my car, just for the record (see left-hand image). But clearly, certain regimes will abuse these systems if they have the power to do so. And this is all in the context of citizens who want a free lunch, and this is from SANSFIRE (right-hand image),

I want a picture like that on top of my car, just for the record (see left-hand image). But clearly, certain regimes will abuse these systems if they have the power to do so. And this is all in the context of citizens who want a free lunch, and this is from SANSFIRE (right-hand image),  where a bunch of security professionals were literally offered a free lunch in return for their personal information.

where a bunch of security professionals were literally offered a free lunch in return for their personal information.

Similarly, social media is part of this, disclosing so much information in largely a public way and it has not gone unnoticed by law enforcement entities,  and there’s an example of college students who knew their local college police were monitoring Facebook for underage drinking, and decided to stage a party that they bragged about. It turned out it was just cake and soda, but when local law enforcement arrived, they were not pleased (see left-hand pic). But still, the idea here is that social media provides a data flow.

and there’s an example of college students who knew their local college police were monitoring Facebook for underage drinking, and decided to stage a party that they bragged about. It turned out it was just cake and soda, but when local law enforcement arrived, they were not pleased (see left-hand pic). But still, the idea here is that social media provides a data flow.

And this isn’t all pie in the sky, this is going to happen. We already see successful prototypes and business plans now, and if any of you, for example, have driven the I-95 between the Washington, DC area north toward New York City, there’s sections of the highway that have cameras at regular intervals. So, we’re not making this up. And then the law itself lags technology, and it’s progressing forward in such a rate that the law just isn’t there yet and will probably never be there.

And this isn’t all pie in the sky, this is going to happen. We already see successful prototypes and business plans now, and if any of you, for example, have driven the I-95 between the Washington, DC area north toward New York City, there’s sections of the highway that have cameras at regular intervals. So, we’re not making this up. And then the law itself lags technology, and it’s progressing forward in such a rate that the law just isn’t there yet and will probably never be there.

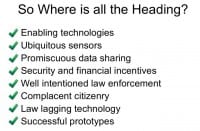

So where is all this heading? (See left-hand checklist) Ok, we got enabling technologies – check, sensors everywhere – check, promiscuous data sharing by citizens – check, security and financial incentives, and well intentioned law enforcement, and complacent citizenry – check and check, and then the law lagging technology and successful prototypes. All the precursors are in place, and we have to now look at where this is all going and make sure that we deflect it onto a trajectory that makes sense, because otherwise, frankly, I don’t think this is going to end all that well.

So where is all this heading? (See left-hand checklist) Ok, we got enabling technologies – check, sensors everywhere – check, promiscuous data sharing by citizens – check, security and financial incentives, and well intentioned law enforcement, and complacent citizenry – check and check, and then the law lagging technology and successful prototypes. All the precursors are in place, and we have to now look at where this is all going and make sure that we deflect it onto a trajectory that makes sense, because otherwise, frankly, I don’t think this is going to end all that well.

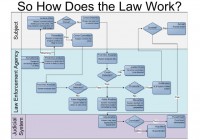

Woody Hartzog: So, how does the law become involved in all of this? Greg just talked about how the technology is in place. The sensors are there to record our activities, but that’s not the only thing that can be automated. And when we’re talking about automated law enforcement, we’re talking about a complete loop, not just with sensors and recording activity, but then storing that activity, processing that activity and making a decision whether to punish someone or not based on that activity.

We actually got three different levels here, where we talk about: there is this subject that is surveilled, the law enforcement agency at various points which can automate decisions, and finally the judicial system to decide if we need some kind of punishment or not (see right-hand diagram). We’ll turn it over to Lisa to talk a little bit more about this diagram.

We actually got three different levels here, where we talk about: there is this subject that is surveilled, the law enforcement agency at various points which can automate decisions, and finally the judicial system to decide if we need some kind of punishment or not (see right-hand diagram). We’ll turn it over to Lisa to talk a little bit more about this diagram.

Lisa Shay: Briefly, I’m going to go over the areas of how this could be automated.

So, looking at the upper left corner of the diagram: if subject’s going about his or her daily life being surveilled by an automated system, which, a la Minority Report, might have a predictive module in it, that then says: “Oh, the subject is about to commit a crime,” and depending on the scenario, could potentially stop that crime, prevent that crime, a la Minority Report, or, in another scenario, could warn the suspect that: “Hey, what you’re about to do is illegal,” and then the suspect has to make a decision to commit the crime or not.

Then, if the crime is in fact committed, there will be some post-processing again by this surveillance system that then decides: “Oh, did the system detect that a crime was committed or not?” Yeah, somebody committed one, but does the system catch it? If the system doesn’t catch it, that’s a false negative. An error’s occurred, but in our personal view, a system that doesn’t catch a crime has got problems, but that’s not the most serious kind of error. What’s worse is if the person says: “Oh, you’re right, I’m not going to commit this crime,” then the post-processing algorithm decides that they did anyway – that’s a much more serious error. We call that a false positive, and that’s where some of the real danger lies.

If the crime was detected, the law enforcement system then decides to prosecute or not. In a normal, everyday, human-based system the police officer on the beat has discretion, but in an automated system this becomes embedded in code, and code is a deterministic process. It will do the same thing every time, and there’s not going to be an opportunity for discretion.

The system then, if it decides to prosecute, hopefully will notify the person that they’ve been prosecuted. Again, one of the things we’re looking for, if some sort of system is implemented, is transparency and notification so that you’re not automatically punished without even knowing what you did wrong. Then, if the suspect is notified, that suspect has the choice to contest it or not, and then, in the judicial process, if they contest, then they can either be acquitted or not.

So this whole system sets up a feedback loop, and in a normal life situation that we have now that’s a fairly slow loop and there’s time for reflection, there’s time for consideration of all effects. In an automated system we fear that that loop gets so fast that the person is punished before they even realize what’s been done to them.

So this whole system sets up a feedback loop, and in a normal life situation that we have now that’s a fairly slow loop and there’s time for reflection, there’s time for consideration of all effects. In an automated system we fear that that loop gets so fast that the person is punished before they even realize what’s been done to them.

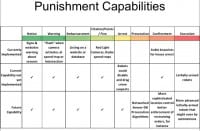

There are lots of opportunities for automating the punishment side of things (see left-hand image). The top row here shows the things that are currently in place; the bottom row shows technologies that could be in place in a couple of years; the middle row shows what could be done now with existing technology if there was a will. And the range of punishments run the gamut from just notice to execution, and we’ll go through a couple of examples.

There are lots of opportunities for automating the punishment side of things (see left-hand image). The top row here shows the things that are currently in place; the bottom row shows technologies that could be in place in a couple of years; the middle row shows what could be done now with existing technology if there was a will. And the range of punishments run the gamut from just notice to execution, and we’ll go through a couple of examples.

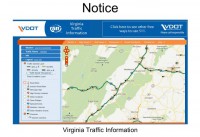

In Virginia and in many other places there are websites that show you where cameras and systems are in place (see right-hand image). There are also places that will send you notice or emails of warning systems that are implemented. And then, I think we’ve all been driving and seeing one of these radar systems (see left-hand image below).

In Virginia and in many other places there are websites that show you where cameras and systems are in place (see right-hand image). There are also places that will send you notice or emails of warning systems that are implemented. And then, I think we’ve all been driving and seeing one of these radar systems (see left-hand image below).  It’s an automatic feedback system; you can see how fast the police think you’re going, you can see what the speed limit is, and then you can make a decision. Now, a la Grand Theft Auto, I don’t recommend trying to make that delta as large as possible. Yeah, if you hit 99 – extra points.

It’s an automatic feedback system; you can see how fast the police think you’re going, you can see what the speed limit is, and then you can make a decision. Now, a la Grand Theft Auto, I don’t recommend trying to make that delta as large as possible. Yeah, if you hit 99 – extra points.

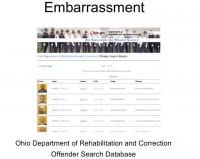

If any of you saw Bruce Schneier’s talk yesterday at Black Hat, he talked about one of the mechanisms that helped a law-abiding society stay functional is that people are concerned about their reputations, and we all want to protect our good reputations. And what some law enforcement agencies are starting to do is put on websites pictures of people who have committed a variety of different crimes (see right-hand image). You can imagine how easy it is to just take a police blotter and write some very simple scripts that put all that information up on a website daily.

If any of you saw Bruce Schneier’s talk yesterday at Black Hat, he talked about one of the mechanisms that helped a law-abiding society stay functional is that people are concerned about their reputations, and we all want to protect our good reputations. And what some law enforcement agencies are starting to do is put on websites pictures of people who have committed a variety of different crimes (see right-hand image). You can imagine how easy it is to just take a police blotter and write some very simple scripts that put all that information up on a website daily.

In a more detrimental way, there are automatic systems for providing citation, points, fines. I know lots of people who have gotten automatic tickets based on red light cameras or speed traps or things like that. There are systems that could arrest people. The bait cars are one example, or robotic systems with a variety of mechanisms on them (see left-hand image).

In a more detrimental way, there are automatic systems for providing citation, points, fines. I know lots of people who have gotten automatic tickets based on red light cameras or speed traps or things like that. There are systems that could arrest people. The bait cars are one example, or robotic systems with a variety of mechanisms on them (see left-hand image).

We can automate the prosecution process as well. Here’s an example of some source code (see right-hand image) from an open source camera security project – again, it’s code that makes a decision as to whether or not a crime has been committed.

We can automate the prosecution process as well. Here’s an example of some source code (see right-hand image) from an open source camera security project – again, it’s code that makes a decision as to whether or not a crime has been committed.

We have systems in place ready for confinement. There’s a whole variety of GPS tracking devices (see left-hand image), Greg showed a couple of examples; your cell phones are GPS tracking devices as well, and there’s a business model for outsourcing this type of enforcement of certain types of punishments. For those of you who are interested, the website says: “GPS is now available for only $3 per day”, so run out and get yours.

We have systems in place ready for confinement. There’s a whole variety of GPS tracking devices (see left-hand image), Greg showed a couple of examples; your cell phones are GPS tracking devices as well, and there’s a business model for outsourcing this type of enforcement of certain types of punishments. For those of you who are interested, the website says: “GPS is now available for only $3 per day”, so run out and get yours.  Track your family members for only $3 a day.

Track your family members for only $3 a day.

And then finally, the ultimate punishment is death, and there are already examples of automated systems that have lethal weapons attached. The ones that we know about right now have humans in the loop, but that technology doesn’t necessarily require humans in the loop.

Greg Conti: So, clearly, there’re advantages to this, but there’re certainly disadvantages as well, and it really depends on your perspective: are you the subject, are you the law enforcement agency, or are you the judicial system? So we’re going to roll though some examples.

Some would argue that these systems provide a more secure society and a safer society. They clearly have the potential, in theory, to offer increased efficiency, and for some they’ll be financial incentives (see right-hand image). And really, what underlies this, I believe, is incentives. Who’s motivated to employ these systems?

Some would argue that these systems provide a more secure society and a safer society. They clearly have the potential, in theory, to offer increased efficiency, and for some they’ll be financial incentives (see right-hand image). And really, what underlies this, I believe, is incentives. Who’s motivated to employ these systems?

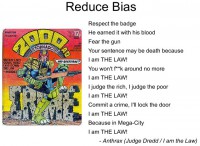

They have the potential to reduce bias (left-hand image), and depending on where you’re coming from, that may be a good thing. For example, there is some great research literally called Driving While Black that shows bias of police officers. There’re also stop-and-frisk activities in certain parts of the country.

They have the potential to reduce bias (left-hand image), and depending on where you’re coming from, that may be a good thing. For example, there is some great research literally called Driving While Black that shows bias of police officers. There’re also stop-and-frisk activities in certain parts of the country.

There’s an ongoing debate between crack and cocaine, and the punishments associated with possession of each, which are very similar substances.

There’s an ongoing debate between crack and cocaine, and the punishments associated with possession of each, which are very similar substances.

There can be protection from abuse, or these systems can be abused, so it depends on your perspective. And if you go back and look at the history of various countries around the world, none are without their blemishes.

And certainly there’re false positives (see left-hand image). If any of you have seen ED-209 from movies, where in Robocop they’re demonstrating the robot: point your gun at 209, and then response: “Please put down your weapon.” He puts down the weapon, the robot responds: “You have 15 seconds to put down your weapon”, and after time runs out: “I’m now authorized to use physical force.” Things don’t end so well.

And certainly there’re false positives (see left-hand image). If any of you have seen ED-209 from movies, where in Robocop they’re demonstrating the robot: point your gun at 209, and then response: “Please put down your weapon.” He puts down the weapon, the robot responds: “You have 15 seconds to put down your weapon”, and after time runs out: “I’m now authorized to use physical force.” Things don’t end so well.

And there are also false negatives, and this is a classic example from Google Street View (see right-hand image). This individual could be doing exercise or could have lost his keys, but these systems could see a crime could be occurring and could miss it. We argue that’s probably better than a false positive in most cases.

And there are also false negatives, and this is a classic example from Google Street View (see right-hand image). This individual could be doing exercise or could have lost his keys, but these systems could see a crime could be occurring and could miss it. We argue that’s probably better than a false positive in most cases.

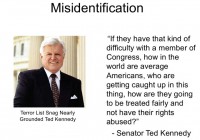

A key component is the identification of the people in the pictures. Well, historically we’ve had issues with improper identification or incorrect identification. A classic example is Senator Ted Kennedy, who got held up at the airport for being on a terrorist watchlist (see left-hand image).

A key component is the identification of the people in the pictures. Well, historically we’ve had issues with improper identification or incorrect identification. A classic example is Senator Ted Kennedy, who got held up at the airport for being on a terrorist watchlist (see left-hand image).

The results of this could be a less complying populace, because we as citizens have to agree; it’s a contract, we have to agree to support the law, to believe in the law on some level. If you take that decision-making out of people’s hands, there can be problems.

The results of this could be a less complying populace, because we as citizens have to agree; it’s a contract, we have to agree to support the law, to believe in the law on some level. If you take that decision-making out of people’s hands, there can be problems.

And there’s always the risk of unproportional response, that the system will respond in a way that’s inappropriate, and this is a Texas speed trap motivational poster, a chain gun (see left-hand image). And clearly, this has the ability to enforce social control on a larger scale, particularly as we move forward. It really depends on whether your local politicians want you to have 32-ounce sodas or not, or a variety of other activities, they can force it with automated means.

And there’s always the risk of unproportional response, that the system will respond in a way that’s inappropriate, and this is a Texas speed trap motivational poster, a chain gun (see left-hand image). And clearly, this has the ability to enforce social control on a larger scale, particularly as we move forward. It really depends on whether your local politicians want you to have 32-ounce sodas or not, or a variety of other activities, they can force it with automated means.

Some won’t like the loss of power – yes, and that’s Batman (see right-hand image), and it turns out Batman was pulled over for incorrect plates, but he was actually going to a children’s hospital and his plates were expired, so they let him go. But it was a good picture, so I thought I’d include it. But law enforcement and, I assume, some in power, like the professional courtesy, perhaps that the current law enforcement system provides to them. Well, they might not enjoy that loss of power if you have an unbiased automated law enforcement system.

Some won’t like the loss of power – yes, and that’s Batman (see right-hand image), and it turns out Batman was pulled over for incorrect plates, but he was actually going to a children’s hospital and his plates were expired, so they let him go. But it was a good picture, so I thought I’d include it. But law enforcement and, I assume, some in power, like the professional courtesy, perhaps that the current law enforcement system provides to them. Well, they might not enjoy that loss of power if you have an unbiased automated law enforcement system.  And there’s a nice example of Montgomery County Police Department in Maryland photographed speeding past the camera with their extended middle finger.

And there’s a nice example of Montgomery County Police Department in Maryland photographed speeding past the camera with their extended middle finger.

The unions and other police-related organizations will certainly have something to say, because efficiency could very well mean lost jobs. There are many questions necessary as we move forward in this area; I will be followed by Woody.

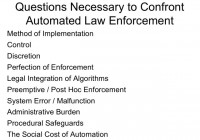

Woody Hartzog: So, what can we do? Chances are that we’re not going to see full automation overnight. It’s going to happen piece by piece. It’s going to automate a little bit on the surveillance side, and maybe a little bit on the decision-making side. And we think that the appropriate response is to start asking questions now, to start demanding answers in that if a system is going to be implemented it will be implemented responsibly, and there are some things that need to be attended to if that’s going to happen (see right-hand image).

Woody Hartzog: So, what can we do? Chances are that we’re not going to see full automation overnight. It’s going to happen piece by piece. It’s going to automate a little bit on the surveillance side, and maybe a little bit on the decision-making side. And we think that the appropriate response is to start asking questions now, to start demanding answers in that if a system is going to be implemented it will be implemented responsibly, and there are some things that need to be attended to if that’s going to happen (see right-hand image).

So, for example, the method of implementation: are they going to use the sensors that we’re carrying around on our bodies, or are they going to mandate that everyone install a government brand sensor. Control: who gets control over the enforcement system? Is it going to be low-level administrators? Is it going to be third parties, perhaps, software vendors that create the code? And if so, what kind of influence are they going to have over the decision making process? Because ultimately, if they’re the ones writing the code, they are the final stop in interpreting law, and there are some potential problems with that.

Legal integration of algorithms: are we going to reach a point where there’s going to be an incredible incentive to personalize the law? So, for example, if I’m a very good driver, I can perhaps drive 10 mph over the speed limit because I’ve been proven to be trustworthy, whereas someone who has a horrible driving record perhaps only gets about 5 mph. And they should perhaps be able to integrate all kinds of algorithms that will be able to determine that.

Do you stop the violation before it happens or do you wait until after it happens and then give a fine? That may seem like a simple question, but I think that the political pressure could be great when these systems are already implemented and entrenched, for someone to say: “You can’t stop the crime; if you can stop the violation of the law, why wouldn’t you stop the violation of the law?” But I think there are significant problems with preemptive enforcement of the law.

System error and malfunction: how much error are we willing to tolerate in a system? No system is without error, we’ve got to make the decision: “Well, if it’s only got a 5% error rate, then that’s good”, or 10%, or 15%, and we need to determine who makes that call.

Woody Hartzog: Some of the big questions, and I think the one that goes to the heart of our talk today, is whether we want perfect enforcement of the law. And I would like to go ahead and say now that we need to dispel this notion that the goals of law should be to achieve perfect enforcement. I think that to be effective laws need only be enforced to the extent that violations are kept to a socially acceptable level. We don’t enforce jaywalking 100%, we maybe enforce it 0.1% of the time, and we’re ok with that. We know that it’s a rule, and as long as everyone more or less keeps it together, we’re fine with that. The goal shouldn’t be perfect enforcement, and that’s one thing we’d like to make clear in this talk.

Woody Hartzog: Some of the big questions, and I think the one that goes to the heart of our talk today, is whether we want perfect enforcement of the law. And I would like to go ahead and say now that we need to dispel this notion that the goals of law should be to achieve perfect enforcement. I think that to be effective laws need only be enforced to the extent that violations are kept to a socially acceptable level. We don’t enforce jaywalking 100%, we maybe enforce it 0.1% of the time, and we’re ok with that. We know that it’s a rule, and as long as everyone more or less keeps it together, we’re fine with that. The goal shouldn’t be perfect enforcement, and that’s one thing we’d like to make clear in this talk.

Besides, another question about perfect enforcement is: many times, particularly, for example, with minor violations, we might violate the law 7 to 10 different times. So, for example, if you’re speeding, and the speed limit is 55, you may go 57, and then drive back down to 53, and then go 60, all in the same trip. And so, if you violate the speeding limit 17 different times in one trip, do you get 17 tickets, or do you get one ticket? And these are difficult decisions that have to be made, particularly if the goal is to perfectly enforce the law.

Greg Conti: Woody, I’d add that we will violate the law, we could try scrupulously to not violate the law, but it’s certainly just a function of minutes, perhaps, an hour, you’ll do something wrong.

Woody Hartzog: Absolutely, I mean, we’re all violators.

Greg Conti: Even with the best intentions.

Woody Hartzog: Absolutely. Another problem that comes with automated enforcement is the loss of human discretion. So, while Greg talked about the fact that discretion can be bad because it can lead to unjust results, discretion can be also very good. It allows us to be compassionate, it allows us to follow the spirit of the law instead of the letter of the law, and it allows law enforcement officers to prioritize enforcement. I’m not going to investigate the case of the low sneakers real hard, because we’ve got some murder over here, and so we prioritize where we want to spend all of our energies. And when you take discretion out of it, I think there’re some significant problems.

Woody Hartzog: Absolutely. Another problem that comes with automated enforcement is the loss of human discretion. So, while Greg talked about the fact that discretion can be bad because it can lead to unjust results, discretion can be also very good. It allows us to be compassionate, it allows us to follow the spirit of the law instead of the letter of the law, and it allows law enforcement officers to prioritize enforcement. I’m not going to investigate the case of the low sneakers real hard, because we’ve got some murder over here, and so we prioritize where we want to spend all of our energies. And when you take discretion out of it, I think there’re some significant problems.

It also leads to the phenomenon known as automation bias. There’s a fair amount of research out there that shows that we as humans, as a group, tend to irrationally trust judgments made by computers, even when we have reasons to potentially doubt that. The idea is: “Well, that didn’t look like the guy, but the computer says that’s the guy, so that’s probably the guy.” And there’s a fair amount of that in the literature, so if you’re going to automate the system, you’ve got to find a way to combat automation bias.

It’s one thing to exercise your opinion and your right to freedom of expression, and it’s another thing to do it when there’s a government camera right in your face. With the ubiquity of sensors and surveillance around, I fear that there will be some serious chilling effects to the freedom of expression in the US, and that’s precisely what the First Amendment was created against, and I think that any automated system should take measures to make sure that there are no undue chilling effects on speech and our First Amendment rights.

It’s one thing to exercise your opinion and your right to freedom of expression, and it’s another thing to do it when there’s a government camera right in your face. With the ubiquity of sensors and surveillance around, I fear that there will be some serious chilling effects to the freedom of expression in the US, and that’s precisely what the First Amendment was created against, and I think that any automated system should take measures to make sure that there are no undue chilling effects on speech and our First Amendment rights.

Also, imagine if, let’s say, the use of speeding violations increases 700% when you automate the system, we all decided to appeal simultaneously; we would crash the system. You have to make sure before you implement any system that there is a mechanism that the infrastructure can handle both the burden of the initial violations being issued and the appeals process that comes after it.

And finally, there’s the issue of societal harm. Automating a law enforcement system to achieve perfect enforcement says two things, but it says one thing in particular: “We don’t trust you. We don’t trust you to do what’s right, and we’re going to go ahead and enforce the law automatically, particularly when you engage in preemptive enforcement.” And so that risk is eroding the necessary trust between the citizens and the governments. That’s critical for any kind of effective governance.

Also there are some moral implications of doing our best to make sure that nobody can violate any crime with preemptive enforcement. What does it say about a society that takes away all accountability for violations? “Don’t worry, you can do anything you want, because if it was bad for you, we wouldn’t let you do it in the first place.” And so I think those are the significant questions that have to be answered in any automated law enforcement scheme.

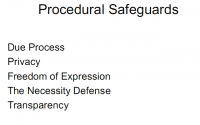

So, what can we do about it? Well, first of all we can ensure that there are procedural safeguards; we can ensure that the basic fundamental due process rights are respected, the rights to notice and a hearing, so we need to know when we have violated the law and we need to have an opportunity to be heard. Privacy rights: we need better Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, we need to solve the problem of privacy in public, which I think that we’re headed towards a conflict over that sooner rather than later, we need better electronic surveillance laws.

So, what can we do about it? Well, first of all we can ensure that there are procedural safeguards; we can ensure that the basic fundamental due process rights are respected, the rights to notice and a hearing, so we need to know when we have violated the law and we need to have an opportunity to be heard. Privacy rights: we need better Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, we need to solve the problem of privacy in public, which I think that we’re headed towards a conflict over that sooner rather than later, we need better electronic surveillance laws.

The necessity defense: all of us probably understand that if you’re headed to the emergency room, probably it’s ok to speed. It’s fine that you need to go 75-80 mph to get to the emergency room that will let you pass on this one. There are many instances that you can imagine where we need to go ahead and violate the law, because the costs of not violating the law are greater. Transparency: who sees the source code? Is it going to be a trade secret or do we all get to see it? And we can look to a lot of the e-voting disputes to learn from this. But I think that open source and transparency in the code is absolutely critical in any automated law enforcement system.

Lisa Shay: So, what can we do about this? Obviously there are countermeasures that are available for all different kinds of problems. Greg and I gave a talk at the HOPE 9 conference earlier this month about a taxonomy of countermeasure approaches.

Lisa Shay: So, what can we do about this? Obviously there are countermeasures that are available for all different kinds of problems. Greg and I gave a talk at the HOPE 9 conference earlier this month about a taxonomy of countermeasure approaches.

And in this community we love to defeat the device. We are all about reverse engineering the firmware and repurposing devices for our own needs, and that’s great, and that’s absolutely a way of providing countermeasures, or man-in-the-middle attacks on the network, or Defeat the Processing. How securely is that database recording all our data? Can we temper with it and make it look different for us? Those are fun and those are exciting engineering challenges, but even more important, we assert, is the countermeasures, or the influence on the actors, the decision makers, the people who decide to build these systems, to emplace these systems, and potentially to regulate these systems, because if we can prevent a bad system from being emplaced in the first place, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

And in this community we love to defeat the device. We are all about reverse engineering the firmware and repurposing devices for our own needs, and that’s great, and that’s absolutely a way of providing countermeasures, or man-in-the-middle attacks on the network, or Defeat the Processing. How securely is that database recording all our data? Can we temper with it and make it look different for us? Those are fun and those are exciting engineering challenges, but even more important, we assert, is the countermeasures, or the influence on the actors, the decision makers, the people who decide to build these systems, to emplace these systems, and potentially to regulate these systems, because if we can prevent a bad system from being emplaced in the first place, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

And that takes us out of our comfort zone, because those are dealing with real people, not with inanimate objects, but that’s a vital task to engage the media, to engage policy makers, to engage law enforcement officials, to engage the people who design, build and test these systems.

Greg Conti: Because once the system’s in place, the local economy, the local leaders become addicted – particularly if it’s profitable – to the financial resources that it brings in, and getting it to slodge is going to be far more difficult.

Lisa Shay: Yeah, better to prevent it than to try and remove it after the fact. And then also you have to worry about competing sensors: when you have these different sensor mechanisms, how are they calibrated? How often are they maintained? How regularly are they maintained? Because if you have different sensors that detect different things about your activities, which one is right?

Lisa Shay: Yeah, better to prevent it than to try and remove it after the fact. And then also you have to worry about competing sensors: when you have these different sensor mechanisms, how are they calibrated? How often are they maintained? How regularly are they maintained? Because if you have different sensors that detect different things about your activities, which one is right?

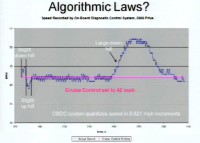

And then we have to look at, really, how these laws are written and how they would be algorithmically implemented. This is a graph of data that I took from my 2006 Prius showing vehicle speed over a period of about 5 minutes (see left-hand image). In this test I set my cruise control to 42 mph, which is the pink line going straight across the graph. At the very beginning I was going a little bit downhill, and you can see the speed rise. And then I went a little bit uphill, and the speed dropped below 42. And then I was on some relatively flat terrain, and yet the speed is still bouncing back and forth. Why is that?

And then we have to look at, really, how these laws are written and how they would be algorithmically implemented. This is a graph of data that I took from my 2006 Prius showing vehicle speed over a period of about 5 minutes (see left-hand image). In this test I set my cruise control to 42 mph, which is the pink line going straight across the graph. At the very beginning I was going a little bit downhill, and you can see the speed rise. And then I went a little bit uphill, and the speed dropped below 42. And then I was on some relatively flat terrain, and yet the speed is still bouncing back and forth. Why is that?

Well, speed is inherently an analog quantity, it has an infinite variability. But the computers on board our cars are digital systems, so they’re doing analog-to-digital conversion, and inherently there’s some quantization error involved. And it turns out that the computer system on board my Prius has a quantization window of about 0.6 mph. So it turns out that that computer will never read exactly 42 mph; it’s going to read 41.6, 42.2, 42.8 and so forth, even though the number that it actually spits out is 4 digital behind the decimal place, so it will be like 41.6374 mph. You think it’s really accurate, but it’s not.

And so, if you just look at this little graph, if the speed limit was exactly what that red line was, there’s about 17 times within 3 minutes that I violated the speed limit, even though my cruise control was set at the speed limit. So, would I get 17 speeding tickets? I hope not, but the law has to take that into account: if anyone of us who is tasked with writing code to enforce the speed limit law, how would you do it? Would you have this kind of level crossing scheme where every time you cross the speed limit on the upward trend, you counted that as a violation? Or would you have some kind of sliding window scheme that said: “Only if the level was crossed for 500 milliseconds or 300 milliseconds,” would you count that as a violation? If there’s three violations within a certain period of time, does that count? Is that 3 or is that 1? So there’s lots of devils in the details.

Woody Hartzog: And I should add that there’s no current infrastructure emplaced in the law to respond to that, because of course these laws were not written with algorithmic precision in mind. For example, take trespassing: it’s a violation of the law to trespass, but if you were tasked with making sure that if a GPS device could probably tell whether you’re on someone else’s property or not, how long do you have to be on the property before it’s a trespass?

Is it a few seconds? What if you’re walking down the boundary and one foot touches over it? How far deep into the property do you have to be to be trespassing? There are all of these little decisions that we make as judgment calls all the time using discretion and deciding whether to enforce the law, that then have to be encoded, and if you make an error, then all of a sudden you’ve systematized the error of the law.

Lisa Shay: That opens up a wide range of research topics. This is an unsolved problem and we’re trying to prevent problems, so the community really has to engage in critical analysis of what are the metrics to decide risk vs. benefit. At what point is it worth implementing an automated system? How much benefit do you have to derive vs. what kind of cost?

And then these systems need to be designed for transparency, they need to be designed for accountability. We submit that they should have manual overrides in them: if the car is going to prevent me from violating the speed limit, in theory that sounds like a great thing, but what if I am running to the emergency room? I’d like to be able to get there quickly. How many of you saw the video footage from the Japanese earthquake, when there was this huge tsunami wave, and there was this little car riding down the road trying to outrun the tsunami wave. If my car couldn’t go past, like, 30 mph on that road, that wouldn’t be good.

So we’re going to have manual overrides, and we want to build in the security systems. You’re all going to find the flaws, and hopefully you’ll tell us, and hopefully we’ll be able to do something about it. But we want to be able to build in some minimal level of security.

And the thing is, this isn’t going to happen overnight. This sort of problem is similar to environmental problems. A little bit of pollution here and there, and then suddenly you wake up one morning and your river’s on fire. You know, it’s the same kind of thing here: you get a little sensor here, a speed camera there, a new computer system in the police department, and then the next thing you know: we’re living in a police state.

And the thing is, this isn’t going to happen overnight. This sort of problem is similar to environmental problems. A little bit of pollution here and there, and then suddenly you wake up one morning and your river’s on fire. You know, it’s the same kind of thing here: you get a little sensor here, a speed camera there, a new computer system in the police department, and then the next thing you know: we’re living in a police state.

So, be careful what you build, and, in summary, these systems can be implemented; there’s sensor technology out there right now that has the potential to automate a lot of the law enforcement process. And if it’s not done well, we could have some really serious unintended consequences, and you all in the audience are in a unique position to help avert these catastrophes.

So, be careful what you build, and, in summary, these systems can be implemented; there’s sensor technology out there right now that has the potential to automate a lot of the law enforcement process. And if it’s not done well, we could have some really serious unintended consequences, and you all in the audience are in a unique position to help avert these catastrophes.

If you’re interested, PDF on these slides has all the references (see right-hand image). We’ve done a talk at HOPE on countermeasures, and we’ve also written a paper for the We Robot Conference that talks about some of this in more detail. And we’d really like to thank John Nelson and Dom Larkin, who were two colleagues that collaborated with us on the We Robot project, who were unable to be here with us today. Thank you very much!

If you’re interested, PDF on these slides has all the references (see right-hand image). We’ve done a talk at HOPE on countermeasures, and we’ve also written a paper for the We Robot Conference that talks about some of this in more detail. And we’d really like to thank John Nelson and Dom Larkin, who were two colleagues that collaborated with us on the We Robot project, who were unable to be here with us today. Thank you very much!

* Skinner Box – is a laboratory apparatus used in the experimental analysis of behavior to study animal behavior. (Wikipedia)

If you wish for to increase your experience simply keep visiting this web page and be updated with the most recent news update posted

here.