This article reflects the lecture for CIS5930/CIS4930 “Offensive Security” at the Florida State University, covering some of the events that compose the history of what’s called “cyber warfare”.

Today’s lecture is about that term: cyber warfare, the history of it, the public perception of it, the reality and the problems we face.

So, here we are in 2013, and the big buzzwords are: the big data, the cloud, and everything’s being connected, and we have like zettabytes of information generated each day, and we’re only analyzing 1% of it. Everyone’s thinking about more effective ways of analyzing that 99% of things. The 99% of things is all these new technologies and they’re being connected together – toasters are now connected to the Internet, perhaps, if you buy the right model.

Before I go on, I want to have a disclaimer saying that the views I present in this lecture are not the opinions of my employers, nor is most of this really even my own opinion. Every single thing I say – news article saying: “This is what happened”. So this is just a lecture based on observation.

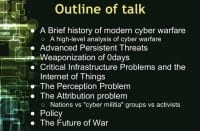

We’re going to go over the brief history, we’re going to talk about advanced persistent threats, we’re going to talk about the weaponization of 0-days, basically cyber weapons, critical infrastructure problems and the Internet of things, the problem with perception and attribution, and we’re going to end with a debate on policy.

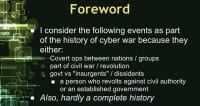

This is not a complete history of cyber warfare, but I tried to go over a lot of really interesting events. I certainly don’t capture all the things that are going on in Europe and Asia; this is more of a Western perspective.

The events that I’m going to talk about are in this history of cyber warfare, because I consider them either to be covert operations between nations or groups, part of a civil war or revolution, or in some effect related to basically governments or government vs. insurgents, and the definition of insurgent actually is, from Merriam Webster, I think, a person who revolts against civil authority or an established government. So that’s interesting to think how that could be skewed for political reasons.

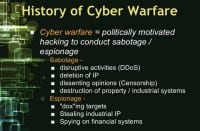

Cyber warfare is essentially a politically motivated hacking to conduct sabotage or espionage (see right-hand image). For sabotage it could be disruptive activities, like DDoS. It could be actually destructive activities, like deletion of IP. It could be censorship. For espionage it could be for the purpose of more real-world espionage, in relating to “doxing” targets. “Doxing” means basically finding out who someone is online. So, if you have a forum username, finding out their actual identity would be “doxing”. That’s just a term that’s been used throughout the ages. Stealing industrial intellectual property, spying on financial systems…

The history of cyber warfare dates back to the cold war (see left-hand image). In 1982 there was a rather interesting event called the Trans-Siberian Soviet Pipeline Sabotage. Essentially, if I get all my facts right, there was a massive KGB operation called Line X. The Soviet empire was basically a couple of decades behind on technology and microelectronics design. And they aimed to breach that gap by stealing all the IT for everything from the West. They trained basically an army of scientist moles to infiltrate companies, agencies, to steal blueprints.

The CIA was tipped off and it’s basically a story that you can read about if you go to the link here. Basically, KGB kind of flipped, gave up all these moles, and instead of arresting all of them what the CIA decided to do was the most brilliant move they could have done counter-intelligence wise, is that they, having known who they are, what they actually chose would be a win-win, either they find all them, arrest them all – the operation is ruined.

What they decided to do instead of arresting them – let them keep operating, but feed them bad info. Feed them schematics for things that they can build. But a week, a month, maybe a couple of months after production line it would fall apart. And so this actually sabotaged Line-X on the inside, because they started doubting the veracity of the information given to them by their own moles. And so the whole thing just kind of fell apart.

So it was an excellent choice. What happened with this Soviet Pipeline is that the CIA was tipped off that the KGB mole was aiming to steal the SCADA system blueprint for pipelines, like big, natural gas, oil pipelines, and they were going to use them somewhere in Russia.

So what the CIA did is they went to the company and were like: “Hey, you have this guy who’s stealing your stuff, so fire him, give him this document instead”. And the document had a little bug in the code, and it was basically a logic bomb that was set to fail. Now, they didn’t really plan it to go this way, but the Russians took it, they built it, they implemented it in their backbone for natural gas and oil coming from Siberia. And what resulted is they caused the pipeline to explode in the critical fork. The resulting explosion was 1/3 of the size of Hiroshima, and we actually detected that we thought it was a nuclear launch on our systems, so it was pretty funny. It’s a good read anyways.

So, that goes back to 1982. In 1999, during the Kosovo War, a NATO jet actually bombed a Chinese Embassy in Belgrade (see right-hand image). They bombed it because it was providing communication support for the Yugoslav Army. 12 hours later the Chinese Red Hacker Alliance was formed, basically, among Chinese citizens, and they’ve been basically active to date.

Essentially they all gathered together on IRC channels and whatnot, and in basically a patriotic effort launched massive cyber attacks at the time against NATO countries. So, essentially, they took down US Government websites, English websites, everything else, as many as they could. And so this is important to talk about, because it culturally marks a much different atmosphere about hacking in the East and that it can often be a patriotic thing to do – we’ll talk about that in a few slides.

And which brings us way ahead of time to 2007 (see left-hand image). Estonia had a park that had some old Soviet memorabilia in it, also a statue. It had a World War II-era Soviet soldier that was a bronze statue. It was removed from the park, and it offended many Russian citizens in the Federal States of Russia. And so, allegedly, what happened after that in response is that a combination of government organizations and Russian citizens collaborated to take down the Estonian Internet. The Russian government officially denies any involvement, but some describe it as the first actual war in cyber space, because it was a month long campaign of nation scale distributed denial-of-service and targeted hacking.

A year later we saw the Russo-Georgian war (see right-hand image), and it’s noteworthy because there were combined cyber and kinetic attacks at the same time, and, basically, websites would get DDoS’ed to, perhaps, distract the enemy, and then the tanks would flank around and take the city.

So, it was a very interesting read. I have for the required reading, which I probably will have listed properly on the right day, a number of articles showing how forensic investigators in Georgia actually tracked down and doxed many of the Russian hackers. They were operating across the street from, basically, one of the main FSB’s sites. So, it’s an interesting read and it has some interesting implications.

In December 2008 there was Operation Cast Lead, and this was also simultaneous cyber and kinetic attacks launched by Israel against Hamas. They would take down, DDoS websites, take down the communications, perhaps the forums or the IRC channels, and at the same time have kinetic force, have troops move in tanks, artillery, etc.

So, the targets in both of these attacks included both state and non-state civilian actors, which is interesting. And it raises some questions about the ethics of cyber war. What is off limits?

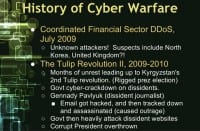

So, in 2009 there was a coordinated DDoS of the financial sector (see left-hand image), and we still don’t know who did it. Suspects include North Korea and criminal elements from the United Kingdom, and it was really never solved, and is still a mystery today.

In 2009 to early 2010 the Tulip Revolution II was basically a culmination of months of unrest leading up to Kyrgyzstan’s second revolution, and essentially it involved, basically, government cyber-crackdown on dissidents, when the government would target its civilians that happened to be expressing dissident opinions – dox them, find them out online. One incident, Gennady Pavlyuk, the guy’s email got hacked, and then they tracked him down and killed him. And what happened in the revolution is that the government was basically overthrown.

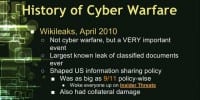

This brings us to WikiLeaks (see right-hand image). In April 2010 it had a number of leaks since this. It’s not necessarily a cyber warfare, but it definitely influenced the cyber warfare and the cyber warfare policy, because this was the largest known leak of classified documents ever. Imagine if since Bradley Manning just confessed, I can say: imagine if Bradley Manning took it and sold it to another country instead of giving it to WikiLeaks, we would be none the wiser. But because he took it and gave it to WikiLeaks, everyone’s wiser about insider threats now. We also lost all that information, but we know we lost all our information. If he sold it, he could probably buy his own island, we’d all be none the wiser, and some other country would know all our secrets.

So, on the US government side, this was as big as 9/11 for obvious reasons: it woke everyone up on insider threats. But it’s interesting that the active leaking of all these documents on the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts actually caused collateral damage. The Taliban used this information to find all the informants that they could and execute all of them. And so there is a number of articles that you can find about that.

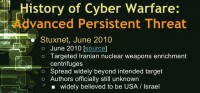

So, while we were still in 2010, in June Stuxnet was discovered; at least Stuxnet v.1.01.1, and everyone in the room should be familiar with it (see right-hand image). It targeted Iranian nuclear weapons and enrichment centrifuges, and it got detected because it spread widely beyond the intended target. It infected basically non-SCADA systems and non-lab systems, escaped the network and hit other systems on the Internet. It is widely believed to be the work of US and Israel collaborating together, according to many news websites.

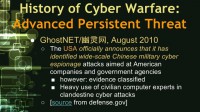

GhostNET (see left-hand image) also was worth talking about in 2010, because the US government officially announced that it identified a wide-scale Chinese military cyber espionage attack or campaign at American companions and government agencies. This is significant, because it’s basically an official declaration of: “We’re a victim here and you are doing it and you need to stop,” basically. It’s all detailed here in a DоD report, it’s unclassified. However, some of the evidence, I guess, is classified and obviously was left out.

The reports indicate that they suspect there’s a heavy use of the Chinese government of using civilian computer experts in their clandestine cyber attacks. However, because their report essentially mounted more to: “Hey, US government, we are actually getting attacked, this is our official stance, so everyone is on the same page working in Washington,” there was no real smoking gun evidence at the time, however. So it is easily dismissed.

Which brings us to 2011, and that was mostly marked by the Arab Spring (see right-hand image), and Anonymous had a lot of activity then. Anonymous may have a number of disagreements with the US government, but in this instance Anonymous and the US government actually agreed on many things; just happened that stars aligned in that way.

So, essentially, the Jasmine Revolution kicked off the whole Arab Spring, and the Tunisian state controlled Internet service provider AMMAR hacked the usernames and passwords to track down dissidents, basically, protesting civilians, and then they would assassinate them. And so Anonymous fought back and did it using DDoS attacks to bring down ISP to help prevent this. At the end of the revolution the corrupt government was overthrown.

Which brings us to Libya. The US debated – the reason I’m talking about this in cyber warfare is there’s an article here describing how the US debated whether or not to use the cyber warfare attacks, simultaneous cyber and kinetic attacks against Libyan anti-air defense systems prior to air strikes. It had been done before, but they declined to do so because they didn’t want to set the precedent for themselves. It’s global politics; politics is really interesting and very vague at the same time. If the big dog in the room does it, it’s ok for everyone else. But if the small guys in the room do it, it’s not ok for everyone else; it’s weird.

So, still part of the Arab Spring, the Egyptian Revolution (see left-hand image): essentially, what started off as a peaceful revolution was met with force by the corrupt government and officials. The revolution was totally organized over Facebook, Twitter and social media, and so the government shut down the Internet. What happened as a result of that is the civilians shut down the government, and I’m sure everyone’s still aware of what’s going on there today, and there’s still hacking activity going on now.

Still talking about 2011 – all the fun that we had with certificate authorities (see right-hand image). We talked about Comodo previously, by the way, .fsu.edu uses a Comodo certificate. DigiNotar got hacked. This is really relevant, because it compromised the Dutch government’s outer-facing websites and as a result DigiNotar was taken over completely by the Dutch government to basically defend themselves and figure out what had been compromised.

In November of 2011 the US government declared that it has the right to meet cyber attacks with military force (see left-hand image). It is significant, because it is basically the first step towards a declaratory policy for cyber war, although this is just basically a rough statement: “We reserve our right to defend ourselves with bullets, missiles and bombs in the event that you hack us”, but that’s vague and doesn’t mean much – it’s kind of obvious, but doesn’t draw the line in the sand.

In November that year the Honker Union was basically a set of hackers that had merged with the Red Hacker Alliance, declared war on, basically, Japan (see right-hand image). And if this happened in the US – a group of hackers declared war on some other country, they would be cracked down. So this is an interesting event. So, Japan announced, basically, plans to purchase a set of islands that were on the coast of China, and this group took great offence to that and decided to launch a campaign of DDoS, website defacing and disruptive activities against Japanese banks, both central and local small banks, universities and civilian companies. So, not so much really government related targets – these were all civilian targets.

In 2013 through 2013 NY Times reported on how it detected a four-month-long campaign of hacking as a retaliation that they alleged for the NY Times investigating the wealth of the Chinese Communist Party’s leader (see left-hand image). And they published an article stating that he had massed fortune over 2 billion dollars while in power, and some groups around the world obviously took offence to that, allegedly these Chinese groups did, and they hacked NY Times systems for over four months, stole all the reporters’ passwords at NY Times and used the same credentials to access the reporters’ personal accounts in non-work systems. And they also hunted specifically for all files related to NY Times investigation. And the reason NY Times alleges that Chinese hackers are involved in this is because the malware or hacking tools used to perpetrate this attack were the same tools used in other attacks that targeted the US military. So, that was an interesting article.

Before I go on, I want to wrap that up. A general note on world perception of hacking (see right-hand image). In general, hackers in the Western world are often anti-government and often get in trouble with government. They’re not usually patriotic, they’re not usually nationalistic, and often 99% of what they do is considered criminal. In the Eastern world there are books stating all this, so I’m not saying this is fact. There is this general perception that basically in the East hackers and groups of hackers are often actually pro-government and can be ignored by the government. There are cybercrime havens. And so, they can be patriotic and nationalistic, and countries are known for being havens for groups like that.

While we’re talking about groups of hackers, let’s just dive into the deep end of it: advanced persistent threats, and talk about the small history here. Everyone should be familiar with Stuxnet. You should also be familiar with Duqu, and Flame came out last year.

Flame was an awesome piece of malware, because it was written by some seriously top notch group of cryptanalysts along with other really skilled hackers, and they were basically able to generate a code signing hash that would tell your system: “Hey, this is signed by Microsoft certificate”. They didn’t have the code signing certificate to use; we shall be familiar with certain authorities being attacked to get code signing certificates. They didn’t actually have the code signing certificate, it was never issued to them. They just found an MD5 collision that would render the same signature.

So they used that and then basically scalped the code to represent it. That was really impressive. So, what happened basically is that once your system is infected, it tells your system that: “Hey, local host is Microsoft Update server”. And apparently, Windows didn’t think twice about that and said: “Oh, great, my own servers, I’ll connect to them, download and install this code in the kernel.” It was really impressive. So, I want to quote the former director of the NSA and CIA, Michael Hayden here (see image above). In this link he talks for 60 minutes on advanced persistent threats, on Stuxnet, Duqu and Flame. He says that “their authors legitimated the art of hacking as acceptable in the stage of international conflict.” He’s obviously not going to say who did it.

Which brings us to what happened after Stuxnet. After Stuxnet Iranian facilities have been hit a number of times (see left-hand image). There were rumors early last year around June that two uranium enrichment facilities in Iran were hit again. It’s unknown whether the viruses did any damage, and it was actually – after the fact that was announced it was denied. This is understandable, and we’ll talk about reasons for denying a breach, denying a hack later on – this is more or less human nature, because it makes you look really bad. It’s bad for morale of the country and whatnot.

What’s funny about this is that allegedly infected machines would lock up around midnight, turn the volume all the way up and play AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck”. So imagine a uranium enrichment facility you can no longer control which is playing Thunderstruck. That’s pretty terrifying if you imagine that scenario.

Earlier this year we talked in January how Reuters and a number of other websites reported that there was a massive explosion that felt over 3 miles away in a major metropolitan city that originated at an underground bunker at Fordow (see right-hand image). And this is the same bunker as known to be used in uranium enrichment. The reason we’re talking about this is that the resulting explosion allegedly trapped 240 people underground. So, when you’re dealing with warfare, even at the kinetics level, if you have to kill people, it’s usually never advisable to target civilians. I don’t know if these 240 people were all scientists or soldiers. But this is worth pondering.

This is basically the satellite view of that facility (image on the left). It’s completely under a mountain, so it’s immune to a bunker buster, which is why the conclusion is that if there was an explosion here, it must have been a cyber weapon, so that’s the reason I’m talking about it.

Within the last months the Mandiant report you should all have heard about came out, and it’s essentially, in 2010 the US said: “We’re officially being hacked by the Chinese government.” This is basically the smoking gun evidence. These quotes (see right-hand image) are from the beginning of this report. Essentially, this is a quote from representative Mike Rogers in 2011.

His statement was: “The Chinese economic espionage has reached an intolerable level and I believe the United States and our allies in Europe and Asia have an obligation to confront Beijing and demand that they put stop to this piracy. Beijing is waging a massive trade war on us all and we should band together to pressure them to stop. Combined, the US and our allies in Europe and Asia have significant diplomatic and economic leverage over China, and we should use this to our advantage to put an end to this scourge”.

I’m not sure how much leverage you have if you can’t stop borrowing from them; to which the Chinese Defense Ministry replied: “It’s unprofessional and groundless to accuse the Chinese Military of launching cyber attacks without any conclusive evidence”. And thus the Mandiant report was the smoking gun as the conclusive evidence.

The report details all the traced activities of what is considered to be APT1 in the malware and incident response world (see left-hand image above). They have identified, they’ve doxed APT1 to be PLA Unit 61398. You read that in their report. Essentially they described APT1 activity as a long term campaign in industrial espionage. They have stolen hundreds of terabytes of data; cyber and physical sabotage probing and preparation. They’ve probed all the critical infrastructure weak points that they were interested in to see if they can cause failures, if they can cause destruction.

They’ve also had a major intention of economic theft and sabotage. They have video evidence of APT1 actors in action: essentially they hacked some of the relay points that they used to do some of their activities and just simply recorded what was going on. So there’s a lot of evidence there. And lastly, they’ve precisely pinpointed the attackers’ location: it’s a building (see right-hand image) full of dozens of hundreds of personnel that they claimed.

Now I want to pause here. I was watching a great panel at the RSA Сonference this year that happened in January, I think. And there was a panel with Whitfield Diffie, I think Ronald Rivest, those obviously huge cryptographers, and there were other really impressive people. I think Rivest said that – this is a really interesting report – however, the last part: how they attributed the physical location.

Essentially, all the analysis up to that point was traffic analysis showing that all these points were following traffic to this location. One set of IPs is located in Shanghai, this one city. Their next step to finding the building essentially is: “Well, we know how many terabytes of data they are processing every day based on their activities, and we’ve traced all their activities. So we have to find some sign that they can handle this”. Well, it just happens that there is only one building in that city that has X number of fiber pipelines going to it, and so that’s their attribution.

And so he said that you can basically take the same report, touch up the details, replace China with US and use the same logic to pinpoint some building in Fort Meade in Maryland and say: “Hey, you guys are doing it too.” So that’s what we’re talking about.

So, China naturally claimed this: “Well, just because you’ve proven that we do it, you guys do it too.” This prompted an interesting debate (see right-hand image). I was watching CNN at the time, and Fareed Zakaria was on, and he had Mike Hayden – I just previously quoted him. And this is a straight quote from the website. He said: “Mike, the Chinese will say in response – or some other Chinese will say – look, you guys do it too. You know, why are you getting so heated up? You know, you ran the CIA and the NSA. What would be your response to them?”

To which Michael Hayden replied (see left-hand image): “Right. I freely admit that all nations spy. All nations conduct espionage. But some nations, nations like ours, self-limit. We steal other nation’s secrets to keep Americans safe and free. We don’t do it to make Americans rich or to make American industry profitable. And what the Chinese are doing is industrial espionage, trade secrets, negotiating positions, stealing that kind of information on an unprecedented scale for Chinese economic advantage. And that’s why I think our response should be in the economic zone.”

So, basically, you might argue this like two kids fighting in the room: “No, you hit me harder, I got to hit you proportionally back right.” There’s a lot of news reports saying that now this is such a big deal and there’s basically spreading rumors of war. And this is a trap, this is absolutely idiotic. Hopefully we don’t go to war over this; that would be really sad, really unfortunate.

So, if we go to war with China, North Korea would ramp up its activities as well, and there’s no telling of what they would do. So it’s just all a bad idea. Things should stay the way they are. They should keep the peace.

We are basically kind of in the middle of a cyber cold war, and the evidence is kind of staring right at us. So let’s talk about, basically, the underground aspect of this, or really, what I would say, the not-so-underground – this is all there and you can find it all.

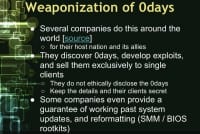

There are a number of companies around the world that will find vulnerabilities, develop exploits for them and not disclose them with the vendor, and sell these exploits to single customers – usually governments (see right-hand image). In essence, they’re cyber weapon defense contractors. There’s a company in France that sells exclusively to NATO countries and agencies, and they have a catalogue of all these fabulous weapons, I think it’s 3 million; you have to spend 3 million just to see what they offer. It’s what many would call an ethically challenged industry. Nonetheless, it’s very similar to parallels of defense contractors, it just happens to be for cyber space. You see that there’s a war going on in cyber space right now.

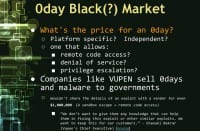

So, what’s the price for a 0day? Think about it. It depends on a lot of specifics (see left-hand image). Is that 0day? Is that exploit platform-specific? Does it only work on Windows? Does it only work on Windows XP 32-bit? Or Windows 8 32-bit? So will it work only on 64-bit? Does it work on any platform, Linux and Windows? Is it some huge fundamental thing that can appear as it’s just gone wrong? If it’s not that, it’s basically super-level exploit. What does it allow an attacker to do? Does it allow the attacker to execute remote code? Is it simply just a denial-of-service exploit? You run it and it will cause the service to crash? Or does it allow privilege escalations?

So I did some searching on my own, I found a contest run by vendors, and they pay $60,000 if you find a vulnerability in their systems. They throw people at Chrome, Firefox, IE, etc. This company is called VUPEN, they have a team of pros, and they wiped the floor. But they didn’t share any of their vulnerabilities with the vendors. The vendors were offering $60,000. They just showed them that your stuff sucks, you guys are noobs. And they said: “We wouldn’t share the details of an exploit with the vendor even for $1,000,000.” And essentially, the exploits at this contest were basically a combination of sandbox escape and remote code execution.

To quote VUPEN’s Chief Executive, they said: “We don’t want to give them any knowledge that will help them in fixing this exploit or similar exploits. We want to keep this for our customers”. And so, here we are, a room full of security researchers, and it’s hard not to see the gorilla in the room, that not only is doing the bad stuff profitable, but you can establish a company and operate completely in the public, servicing a host government. Is this even really a black market at that point? They advertise their products on Twitter.

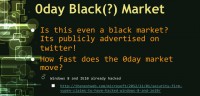

So, how fast does this market move? Hopefully it’s not that fast, hopefully we could gather on the cutting edge. Well, according to their Twitter feed, as they’ve already hacked Windows 8 and IE 10.

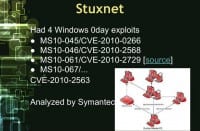

So, let’s talk about Stuxnet, because that’s been extremely analyzed, and the great people at Symantec have done some amazing analysis of it, and just recently they announced that they discovered and have finished analyzing Stuxnet v.5. Stuxnet 1.0 had 4 Windows 0day exploits, and I have them listed here (see left-hand image) so you can look them up yourself.

Essentially, three of them allow for remote code execution, and one allows for administrator privilege escalation (see right-hand image). Now, if you’re buying this on the black market, it’s super expensive, because they’re not willing to disclose these things for a million dollars to vendors, and there was obviously remote code execution plus sandbox escape.

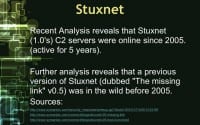

Symantec’s analysis of the missing link of Stuxnet found that it was in the wild before 2005 (see left-hand image). So, that means that we’re approaching 2015 and we’re ending the first decade of, essentially, cyber warfare, so much so we can have an hour-long lecture.

Since we’re talking about that level of attacks, it’s important to know supply chain attacks (see right-hand image), because that very first event that I talked about, the Siberian sabotage, was actually a supply chain attack. Even though they were stealing from our supply chain to use in theirs, we sabotaged what they were stealing and caused that explosion.

So the supply chain attack does not mean basically running and gunning on the enemy’s convoy. It means, essentially, if they are using your products and you control that company, this manufacturer of the microchips, or you control the borders that it’s being transported through, you can manipulate that product. So you can install hardware backdoors, you can install remote kill switches.

And so the state, if it controls the country, can influence that product’s design, its features, or perhaps secret features, and even perhaps have security backdoors, or a blatant lack of security to be easily exploited (see left-hand image). The problem with that is if you install backdoors, someone else finds out about them, it’s not just you.

There were a lot of rumors that a Chinese company called Huawei that does telecommunications technology does this, as secret backdoors, but I don’t know anything about that.

There’s rumors of this going on, conceptually it’s not unprecedented – it happened in the Cold War. So, what happens if these backdoors get hijacked, perhaps by other nations? We’re buying those North Korean routers, and then actually Iran finds the backdoor, and they’re attacking us, and it looks like it’s actually North Korea. Who do we attribute and how?

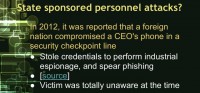

Aside from state sponsored supply chain attacks, there’s actually been instances of state sponsored personnel attacks (see left-hand image). In 2012 it was reported that while a CEO was going through a security checkpoint in an airport, where they take all the stuff and put it under an X-ray scanner, they took the smartphone he had, dumped all the data off of it, and stole his password and his enterprise credentials for his company, logged in as him and stole a ton of IPs, and then went on to actually use his account to perform spear phishing. And the victim was totally unaware of it until much later.

As we’re approaching billions and billions of things connected to the Internet, imagine supply chain attacks for what we are calling the Internet of things. Everything’s being connected. I like this diagram on the right (see image). It’s the absolute worst diagram I could find. You have wires running from your toaster into the water of your toilet into a TV that’s showing you what’s inside the toaster. It’s like: “What?” Did the Congress put together this diagram?

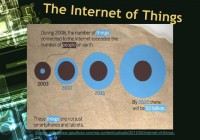

We have basically a vast, mind-blowing amount of things that are connected to each other, that your grandparents would never have thought it would need a microchip in them. This is a great diagram to put things in perspective (see left-hand image). In 2008 the number of things connected to the internet exceeded the number of people on Earth. In 2020 there will be 50 billion things connected to the Internet if we keep going at this rate.

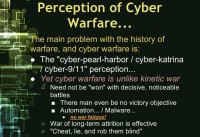

So this is all really hard to understand, especially if you’re making laws and policies to secure this stuff, and people really fail to see how connecting all these things together can have a real impact. They could be exploited by attackers. And so, because they don’t want to understand the problem, everyone is looking for a cyber Pearl Harbor, cyber Katrina, cyber 9/11. I just want to take these people and choke the life out of them, because it’s absolutely idiotic. And I’ll talk about why it’s idiotic.

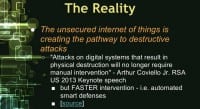

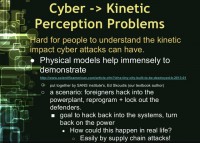

The reality of things is that the unsecured Internet is creating a pathway to destructive attacks. To quote Arthur Coviello – he was a keynote speaker at RSA 2013 – he said that attacks on digital systems that result in physical destruction will no longer require manual intervention (see left-hand image). In other words he’s talking about the Internet of things and how we’re creating so many more pathways for things to go wrong, because everything’s connected.

I may be able to attack you not through basically your machine – perhaps, through some device that has a computer in it, and I can host my malware there, use that as a pivot point, perhaps on your fridge; and perhaps poison you and kill you by manipulating things in your fridge, or something like that. Or perhaps, infect the entire city’s air conditioning units and cause them all to turn off and on at synchronized times, and that will cause effectively a whiplash on the power grid. These are little things, if you understand how these things work it just blows your mind. And so, in effect, what he’s trying to say is that there’s going to be so many things that can go wrong; we can’t rely to responding to these things in a manual way. We have to have faster and smarter intervention. We have to have automated smart defense systems to deal with these things.

So, here is the perception: we only see the tip of the iceberg, and no one really understands what’s below (see right-hand image). The reality is that it’s really worse than what we’re seeing. But we don’t know how worse it is. Before we proceed, it’s wise to note human nature that no one admits, no one likes admitting they got hacked. Admitting your company got breached is really bad for business. So, many of these things actually get pushed on the road.

So our perception is naturally just worse due to human nature. So, what will it take to breach this gap? It’s a really tough question. Everyone’s hoping for these cyber Pearl Harbors and Katrinas, and it’s kind of understood that that will breach the gap. Do we really have to wait for something that bad? That’s what people at the RSA and this conference are trying to ask. It’s a good question. Why do we have to wait for this? We know it’s that bad.

Well, it really comes down to the fact that the kinetic aspect of cyber security, the kinetic impacts are really hard to think about. And as for warfare, cyber warfare is totally unlike kinetic warfare (see left-hand image). When you launch a Tomahawk group missile, it’s gone, it’s spent. When you launch a Stuxnet, someone can copy and paste it and use it somewhere else.

And battles in cyber space need not be won with decisive attacks. If I get a backdoor in your system, I can just own you all the time. There also need not be any real victory objectives – it’s not like I go and take capital and it’s game over. And then everything in cyber warfare can be automated: we have malware, Trojans, etc. We’re not going to face war fatigue; we’re not going to have families with soldiers overseas, missing their daughters and sons. There’s not going to be a public protest. Cyber warfare can go on forever. So, it can be basically a very effective tactic for a long-term attrition to perhaps tip the balance of power. And effectively, you can play very efficiently by just cheating, lying and robbing other people blind.

The cyber-kinetic perception (see right-hand image) is one of the main problems. There’s some good work being done. I think the SANS institute, they’re putting together a mock town, like a model train set town, and it’s a cyber war training simulator. They have basically a little military base, a hospital, a power plant; essentially they have all these interesting scenarios, like enemies have hacked into a power plant and they’ve locked out the defenders. You have to hack in yourself and kick them out and turn everything back online.

There’re people who’ve hacked missile launchers at the military base. You have to hack them to disable them or they’re going to blow up the hospital. It’s obviously toy stuff, but it’s unfortunately what is necessary to make important people in this country and in the world understand the consequences of what can go wrong in cyber space.

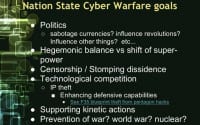

So, let’s talk about perhaps the goals of, say, if FSU or some country wanted to go to war with UF and other country. What goals would you have? We’d probably have political goals, we’d want to influence perhaps the value of our students over theirs – our degrees are worth way better, we pump out X number of degrees, our GDP is way better than yours.

We may want to sabotage your students. We perhaps want to influence the balance of power, perhaps make our football ratings look better, or stuff like that. We perhaps want to censor bad stories about us, or stomp out the dissidents. We perhaps want to steal their good ideas, steal their research and aim for bad people, so we can keep our competitive advantage. And so we want to, if we’re going to face them in football, maybe spread rumors on our forums: “Hey, our star players are down”, so they change their tactics.

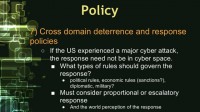

But also it’s more real setting on the world stage. It’s completely reasonable to engage in cyber warfare to prevent war, especially to prevent world war and nuclear war. It obviously was going on with Stuxnet and Iran’s attacks. Whoever was behind them is obviously trying to berate them for having nuclear weapons, because they believe that they will use them. They’ve only told the UN that they will do that a dozen times.

So here’s what the common perception of what a cyber war would look like. There will be, basically, targeted efforts and pervasive cultural efforts to launch war. And there will be all the time large-scale denial-of-service. And critical infrastructure and finances will constantly get hit. And there will be secrets being stolen. Maybe, at that point stealing secrets doesn’t matter, unless you’re stealing intelligence secrets. But there would likely be large-scale sabotage, and it would likely be combined with kinetic actions, because if you cause that many things to go wrong, you’ve obviously provoked whoever you’re attacking into actual war.

And that’s what everyone’s looking for. They’re looking for the actual Pearl Harbor, that rank of war setting. Why? If I were going to be launching a cyber war against a country, the worst outcome will be to provoke you. I could happily steal everything I wanted and rob you blind. Why would I want to trigger an actual war? I can beat you on the world stage if I can steal all your secrets, if I can sabotage your financial secrets and lower your GDP. I can just naturally economically overcome you if I steal everything you do.

Such a war has yet to be seen – really, I guess until the recent debate now, where Michael Hayden’s coming out and saying: “Yes, we all hack each other, but you guys are doing it for economic advantage, and we’re not”. Whether or not that’s trustworthy – you guys decide.

So, this long-term attrition-based cyber warfare was actually seen during the Cold War with KGB’s Line X initiative to steal all this intellectual property from us to catch up on the decades of technology that they’re behind on. And so, in such a setting it would be interesting to see whether or not there’s targeted effort from a small set of actors or there’s pervasive cultural effort. Surely, that’s going to depend on what part of the world you are in and the culture there.

And so, large-scale sabotage causing things to go wrong, causing things to pull up here, in a long-term attrition-based cyber war it’s actually unlikely. There will likely be large-scale espionage, those secrets, IP, perhaps, finance will be targeted much more than critical infrastructure. The goal is to attack yet avoid provocations, and essentially to shift super power status over time, or some sort of status over time.

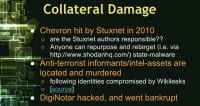

Since we’re talking about war at that level, it’s interesting to kind of ponder the possibility of collateral damage and ponder the question of when a virus or an exploit can be a war crime. Because as we’ve seen in these APT efforts that caused explosions in various places and perhaps trapped the people underground, we know that cyber-triggered kinetic actions can kill people.

And so, even in the instance where they don’t kill people; Chevron actually had its systems massively hit by Stuxnet in 2010. Who’s responsible for that? Is whoever wrote that responsible to pay them in damages caused? And also in document leaking talk, we’ve talked about how the informants revealed in the WikiLeaks dumps were rounded up and assassinated. And the instance that DigiNotar was actually used as a stepping stone in an attack against the Dutch government, which I guess is pretty unlikely. The result of that is that they actually went bankrupt, and they’re a civilian company.

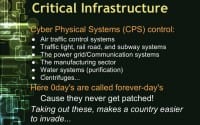

Imagine all the collateral damage that will be caused by hacking cyber physical systems: it will bring down air traffic control systems, traffic lights, rail road, the power grid, manufacturing sector, perhaps in terms of economic collateral damage, and so on (see right-hand image). And here it’s really important to know that if you’re dealing with security here, 0days and cyber physical systems terminology is equivalent to forever-days, because these things never get patched. So if you happen to have these systems connected perhaps to Internet at a lab of manufacturing plant, and the virus gets in on the systems, this is going to get attacked, perhaps.

So, in the instance that your systems are never patched: if a 0day is weaponized, it gets out there and gets used, it can be basically reused by anyone else forever. If you’re in that room and you decided to pull the trigger on this plant or that plant, for every decision you have to ponder the real possibility of it being used anywhere else at any time. I think it’s crazy.

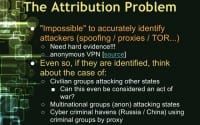

So let’s stop talking about that and switch gears to the problem of attribution (see left-hand image). It is almost impossible to accurately identify attackers, because they can be spoofing all their IP addresses and some settings. They can be behind proxies, they can be using TOR, and really, for real attribution you need hard evidence. There’s many services that allow any sort of activity on their networks as long as it’s not child porn. For instance, I have a list here of anonymous VPN services that actually do take your anonymity completely seriously, and in a few years you can’t be tracked whatsoever. They don’t keep any logs; even if the government was to subpoena them, they would simply reply: “We have no logs, come see yourself”.

Say, you got some dumb attackers, and they don’t use these services, or perhaps services that they’re using get hacked and they start video recording exactly what they’re doing, like in the case of Mandiant report. And, say, they’re identified. Now we have to think about the case of what if it’s a civilian group inside the country doing the attack? Is it affiliated with the government? Is it sanctioned by the government? Is it covert and the government doesn’t know about it? Attribution here is very much affected by those possibilities.

Say, we get hacked by a civilian group from another country and it causes the next 9/11 – thousands of people die, everything goes wrong, but it’s a civilian group. Can that be considered an act of war? And if they legitimately were sanctioned by their government? If it is, how do we prevent our people from doing it? How do we prevent our citizens from doing it? This is a really difficult problem. And what about the case of multinational groups that spend multiple borders perpetrating such attacks? And then what about groups that are simply, perhaps, in one country, that are utilizing the safe haven nature of other countries to launch their attacks against you?

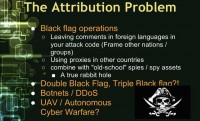

And then this brings us to black flag operations (see right-hand image). Perpetrating attacking, impersonating as person B, some other team; or perhaps using your weaponized 0day and leaving comments in Chinese or Greek or Turkish to obviously throw off the investigation and make them think that other people did that.

And then in the instance that you’d really want some people down the rabbit hole, doing this is basically like a double cross or triple cross, a double black flag or a triple black flag, and then using botnets to do this. That spans all countries. You have to hunt down the C2 network, you have to trace where the bot masters are actually logging in, and even then it gets crazier.

And now we’re approaching an era where UAV drones are going to be everywhere. What happens if one gets hacked and is used for some malicious action? Attributing and finding out the hack – the data to do that may not be in the black box for that drone if it gets crashed. So, that’s a real rabbit hole of possibilities. And then, dealing with repurposed Stuxnets (see left-hand image) and things like that…

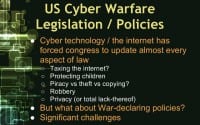

So, how do we begin making policies and laws with all this uncertainty? It’s really a problem that I’m glad I don’t have to fix. However, I’m going to complain over how poorly those in power have faced it, quite gleefully. Cyber technology and the Internet has forced Congress to update almost every aspect of law: taxation, protecting children, piracy, theft and copying – it’s really interesting to note that computer piracy is not really theft, you’re not depriving the original owner of a physical entity that they once possessed; you’re copying it. So that’s had to change all that law, addressing the criminal problems that arose there.

And then laws about privacy, or perhaps the total lack thereof nowadays. But what also about the war-declaring policies? Establishing a policy here has faced significant challenges.

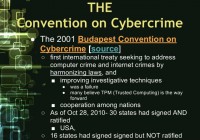

And so, in terms you guys should be familiar with, it’s the Convention on Cybercrime (see left-hand image). It’s happened in 2001, and I think it’s happened a number of times since then. It’s effectively the first international treaty seeking to address computer crime and Internet crimes. It did this by making strides to harmonize laws. That means, basically, making laws compatible with each other across the nations, and to also make efforts to improve investigator techniques.

At that time it was a complete failure, the latter part – improving investigator techniques. Attribution on the Internet is really hard, because there’s no identification requirement to use the Internet, and you’ll hear all sorts of advocates for all sorts of different solutions here requiring people to have a universal ID to use the Internet, so there’s no more anonymity and anonymity is dead, and then using TPM to establish that. I don’t know about that.

And also in this convention, the foremost thing they tried to do is increase cooperation among nations and stop fighting. So, as of 2010, 30 states had signed and ratified this treaty and have it enacted in their law. The US is one of them; I believe China and Japan are ones too, so that’s really interesting to think about. Also at the time 16 states had signed but had not ratified it in their law.

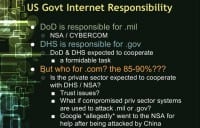

So since we’re agreeing to basically play ball, let’s talk about the breakdown of responsibility the US government has for securing the Internet (see right-hand image). The DoD is responsible for .mil, and DHS is responsible for .gov. But who’s responsible for .com and policing that? How do you even go about suggesting who should do this? If a government agency or department does this, is the private sector expected to cooperate with them? And if so, you’re going to have trust problems; even if it’s DHS, and especially understandably if it’s NSA.

What if compromised private sector systems are used to attack the .gov and the .mil systems? Distrust has been overcome; distrust issue has been conquered in the past. When Google was being attacked by Chinese actors or actors originating allegedly in China, they went to the NSA for help allegedly – I only found rumors of this.

Now think about why it would only be kept as rumors, and you don’t go out and say it? Your customers use you because they value the sense of privacy they get with your services. When you go and cooperate and collaborate with a government agency, it can ruin that value that they have in your service. So you have problems here. Perhaps the only way to do it is to do it in secret, to collaborate in secret.

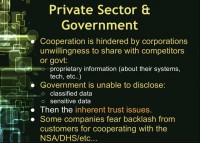

Let’s talk about the extent to which they can collaborate, though. Cooperation is hindered by corporations’ unwillingness to share with their competitors or the government. You can’t just bring Google, Microsoft, Apple and all these people in the same room, and someone from NSA or DHS at the table, and expect them to fully cooperate without disclosing perhaps details on their own security setup, as these details can be used by their competitors against them.

Likewise, government is unable to disclose classified data or sensitive data – maybe they actually have the inside knowledge, they have a mole on the enemy team, and this team is hitting all these private sector companies; and they actually have all the info on their mottos, their goals and state objectives, but they can’t share that because it’s classified. So, they can’t share classified and sensitive data, so they are limited to how much they can disclose. And even then, if you get this level of cooperation, you’re going to have a very real fear these companies will have public backlash.

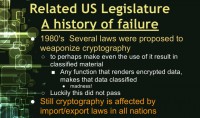

So, let’s talk about US legislature in this area, or what I subtitled as “a history of failure” (see right-hand image). In the 1980s – several laws that proposed to weaponize cryptography; imagine how different the Internet would be today if we had no cryptography: you wouldn’t have SSL, you wouldn’t have e-banking, you wouldn’t have e-anything. Thankfully these efforts did not pass. However, cryptography is still affected by import/export laws in almost all nations.

And so, sure everyone in the room has heard about SOPA and PIPA (see left-hand image), and that was in 2011 and in massive protests. Essentially all this was – was a draconian approach to filter DNS systems, to basically censor them and blacklist unapproved websites for the purposes of stopping piracy. Piracy was poorly defined in legislature, and thus could be manipulated. It would have established the power for political and corporate censorship of the Internet. Luckily, this did not pass.

In that section of that subtitle I’m just talking about related things that I think are perhaps more interesting, unless it’s just a bad idea, because it doesn’t stop you from typing in an IP address of where you want to go. It really is not a solution. It did way more bad than it did any good. It actually didn’t do anything to solve the problem. It completely didn’t solve the problem, just created more problems. That’s why I consider it a massive failure.

So, this is a bill being considered (see right-hand image), I don’t think it’s been signed into law yet; I’m not familiar with the history of the decisions or rulings of it. But effectively it grants the executive branch to shut down parts of the Internet essentially for the purposes of national security and defense. So that’s worth considering.

But more importantly, the Cybersecurity Act of 2012 (see left-hand image), last year it was proposed. It did not pass. Its stated goal is to set cybersecurity standards for critical infrastructure operators, and would have encouraged companies and the government to share information with each other about cyber threats to basically establish that level of cooperation, because currently there is no level of that cooperation. We’re trying to meet that treaty, that treaty is a good idea. Honestly, this is my opinion: I believe that treaty is a good idea, if you can get everyone to do it. So even if you’ve ratified it, you have to work towards that.

So, the main purpose of this was to raise situational awareness by sharing information on critical infrastructure, and that’s where we can be hit the hardest. Opposing groups cited privacy concerns, most understandably, very similar to CISPA, which we’ll talk about next. But the bill explicitly prohibited sharing citizen data with military and intelligence community groups. So, I think having this privilege in your legislature makes sense and it’s a good idea.

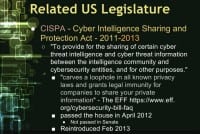

So, let’s talk about CISPA – Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (see right-hand image). Many people I know are big fans of this and bills like this. As it’s written, it has other problems. Its stated goal is to provide for the sharing of certain cyber threat intelligence and cyber threat information between intelligence communities and cyber security entities, and for other purposes.

The end “for other purposes” is really what kills it, because the way it’s written so open-ended, that to quote the EFF: “It carves a loophole in all known privacy laws and grants legal immunity for companies to share your private information”. It passed the House in 2012, but did not pass in Senate; I think it was filibustered down.

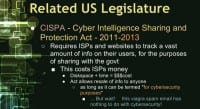

It’s been reintroduced this year (see left-hand image), this February it was reintroduced. In effect, it required ISPs and websites to track a vast amount of information on their users for the purposes of sharing with the government, for cybersecurity purposes and for other purposes.

This costs ISP companies money, because disk space plus time equals money. Basically, as a trade back, the act allows them to resell the info to anyone for cybersecurity and other purposes. What do you mean by cybersecurity purposes? It doesn’t define that precisely. The language is so vague it can be everything.

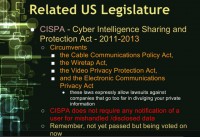

So, my information could be resold for cybersecurity purposes, and then I can get Viagra spam, and that, clearly, should not be enabled by law. The bill directly circumvents the Cable Communications Policy Act, the Wiretap Act, the Video Privacy Protection Act, the Electronic Communication Privacy Act as well (see right-hand image). So these laws expressly allow for lawsuits against companies that go too far in divulging your private information.

However, the CISPA terminology goes so far to directly state that companies are not required to notify their customers if that data is mishandled in compliance with CISPA. And that goes for the government as well. So remember this is not yet passed but it’s being voted on now.

So, what this means is if all these people are tracking you, it’s like you’re sharing information with the government. If I want to spy on you, I don’t have to limit options to just hacking you or hacking government, or hacking your favorite site. I can just hack these other sites as well. I have X number of ways, X number of more ways to get at you now. So this creates many problems.

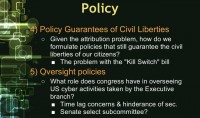

Now I will go over, basically, the policy hurdles that the West faces (see right-hand image), specifically this country, the United States. This portion of the talk is largely taken from Professor Michael Nacht’s 2011 work called The Cyber Security Challenge. I had the pleasure of meeting him and listening to a number of his presentations at the Sandy Summer Institute this Summer.

He was introduced to the group as a living national treasure, and after looking into his history I can definitely see why – because he has been instrumental in shaping US policy all throughout the Cold War and has so many insights into the inner workings of government, the executive branch and foreign policy and how everything really comes together. And so his insights on cyber security policy and how they were paralleled to, basically, nuclear deterrence in the Cold War are really worth looking into. So that’s what we’ll be going over in this section.

So, we face 8 hurdles. The number 1 hurdle he declares is, basically, we lack a solid declaratory policy (see left-hand image). By that I mean war declaration policy. We have said we reserve the right to use military force in response to cyber attacks, but there’s no real line drawn in the sand. It’s left intentionally vague. And the problem with specifying: if you cause X amount of damage, an attacker will always just do X-1 amount of damage as long as possible; he’ll asymptotically basically approach that line in the sand.

So, because of that challenge and all other things it hurts us more than not to have actual line in the sand drawn, because when all the plans for how we should coordinate in event of a major cyber attack against perhaps our military forces, or instead perhaps our command and control systems, or perhaps instead our electrical grid, financial networks – there’s no unified plan as to what we should do, what initiatives should be basically started in the event of some major attack.

Secondly, there’s no real deterrence policy (see right-hand image). In the nuclear, basically, Cold War, it was a game of mutually assured destruction: “If you attack us, we’re going to wipe you out and everyone’s going to die”.

In cyber space you can see some parallels, because, say, I have basically super Stuxnet. If I attack you, it’s going to be in the wild and somebody can copy/paste it and use it against everyone else. So, it requires some finesse in using these weapons, because they’re not like atomic bomb – once you use them, they’re out there and they can be reused. So it’s a whole different game, but there’s some sort of similar deterring parallels.

But at the same time there’s no attribution at the same level that there was in the Cold War. If an ICBM were launched, you can detect it from space and from radar systems. You can detect what part of the world it’s been launched from. Cyber attacks – there’s proxies, there’s TOR, there’s anonymous VPN, and then people could be on their own home turf or they’re from another country and they’re attacking you. Attribution here is very difficult, so therefore that also compounds the deterrence problem and hurdle. And even when attacks are detected, and perhaps even if there is attribution, some level of attribution, the damage that was done may not actually reveal until later: maybe they’ve inserted a logic bomb that will basically detonate half a decade or a decade later.

The third hurdle is there’re no well-established policies on who are to be the authorities and what their responsibilities are in the event of, basically, cyber attacks (see left-hand image). If we responded with military force, if one country responded with military force to another country’s cyber attacks – that would indubitably involve some violation of that nation’s sovereignty.

So, that throws into the mix all sorts of legal concerns: you have to establish, basically, legal basis to conduct such operations to not be seen as a bad guy in the world court. And so, there’s no real legal basis for establishing and initialization of military conflict as a result of some sort of cyber conflict; that cyber and kinetic tie isn’t really there. The cyber and kinetic attacks have been used in conjunction at the same time. But that’s after kinetic attacks have already started, such as in Russia or Georgia. More, when Russia decided just to go ahead and invade its neighbor, they just used cyber attacks to supplement their strategies.

And it’s worth noting that establishing these basics for traditional kinetic attacks, traditional military force attacks, takes weeks to months. And in cyber space we all know that things happen in microseconds and milliseconds. So there’s this huge time lag and a speed gap as well in order to establish effective policies. You can have policies where we’re going to go after we suffer some major cyber attack, go to our congressional committee and find out what we should do. That’s going to take weeks, so you’ve got to not only defeat all these legal hurdles for tying the cyber and kinetic legal problems; you have to also establish policies that are going to be effective and not suffer from massive amount of lag of bureaucracy.

The fourth, and perhaps, what I can say is one of the most important ones: you have to have policies that guarantee civil liberties. As we’ve seen with the SOPA and PIPA bills, as well as CISPA, they do nothing to solve the problem they declare that they intend to solve. And they are easily circumventable. And on top of that, they create exponentially more civil liberty problems. SOPA and PIPA absolutely do no possible good being proposed.

CISPA does nothing to protect civil liberties; there’s no responsibility to notify a citizen if their data is mishandled under following, under compliance with the CISPA act. The CISPA act is the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act. It circumvents all these privacy acts, and these acts expressively declare that you’re allowed to initiate lawsuits against a company that goes too far in divulging your private information. However, CISPA allows them to resell and share data with anyone for cybersecurity and other purposes.

So this does nothing to address civil liberties; it actually does everything to trample on them in some regards. Although, perhaps, the original authors of these bills didn’t mean for it to go this way. If you don’t take care to address civil liberty concerns and guarantee that established civil liberties will be maintained, you are going to basically be exacerbating the whole cybersecurity problem.

So, which brings me to the next and related point – it’s that you have to set some sort of effective oversight that insures that, basically, the civil liberties are being guaranteed, that all these other policies are working, and that it doesn’t also bureaucratically lag down the whole process. You can have an oversight committee that slows down everything by weeks or days. And then there has to be consideration as to establish some entity to be in the role for oversight; perhaps Congress. And we’ve all seen how few Congressmen really even understand the Internet.

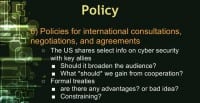

Since we’ve just finished talking about sharing information and how to establish policies that do it to guarantee civil liberties, the reason for sharing information is to increase situational awareness (see left-hand image). If you’re completely unaware of your situation, you’re completely unable to defend yourself. If you don’t know you’re being attacked, you can’t really do anything to stop being attacked, unless you just get lucky. And we all know that you can’t just rely on being lucky in this field.

So there’s a great need to actually share such cybersecurity information, not just at a domestic level – between companies and between government and private industry, but between governments and between countries at an international scale. So, the US already shares select information intelligence on various different things with its key allies, but should it broaden the audience for sharing information on cybersecurity?

Perhaps there is a botnet going around that utilizes some 0day and is just spamming everything and taking down stuff, and perhaps stealing intellectual property. What could it gain from broadening the audience of information sharing at government levels? Perhaps, a lot; however, when you give something, you should always expect something back, so if we broaden the audience, what should we expect to gain from said cooperation?

Perhaps, there could be formal treaties established in this area as one way to address this challenge, but that may be too constraining and may end up being a bad idea, as treaties often, when implemented, end up going wrong. Once they’re ratified, they get misconstrued in law, and everything gets twisted and goes wrong. So, it’s an interesting hurdle in itself.

And so, speaking of deterrence, since the Internet is basically worldwide, we do need to share this information with a more global audience to raise situational awareness. We also have to have some sort of collective effort for deterrence (see right-hand image). This is basically a messy area, because some will argue that the best way to do this is to have universal cybersecurity laws, universal intellectual property laws that expand the whole world. I don’t know how realistic that is.

Another policy hurdle is you have to strengthen the private sector and government cooperation (see left-hand image). I think the recent one was trying to do that, and it was called the Cybersecurity Act. Compared to the rest it was well-written, because it made expressed requirements that citizens’ data is not shared with the intelligence communities, it’s not shared with the NSA, and not shared with this and that, it’s not shared with the military, because this act is only for raising cyber security awareness for critical infrastructure.

So, basically, the DHS and FBI will collaborate with critical infrastructure companies, so your power grid, your air traffic control, your sanitization for water, and traffic control will all collaborate; they’ll all monitor info. And now, clearly, we’re not sharing our social security numbers and stuff like that with all of these companies, and we’re not usually visiting them on a regular basis, so it leads less to them being able to track your data, because you probably pay these bills once a month. So it’s not as intrusive as CISPA, perhaps. It also makes expressed guarantees to establish least privilege in the bill itself for who needs access to this information, not just: “You can share it with anyone for cybersecurity or other purposes”. Obviously, that’s the worst wording you can use.

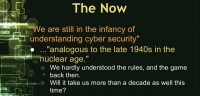

He wraps up his wonderful article by saying that we are still in the infancy of understanding cybersecurity (see right-hand image). I completely agree. He says it’s also analogous to the late 1940s in the nuclear age. We hardly understood the rules and the game back then. And hopefully, it will not take us more than a decade this time as well.

In the future (see left-hand image) we’re probably going to expect seeing much more state-sponsored cyber attacks and malware, and then those being repurposed by criminals. More research in honeypots and counterintelligence systems that basically lure in the attackers and then waste their time – this is my research area. And then there’s a lot of push towards globally adopting IPv6, and what this possibly means for attribution, and there’s a lot of myths about that. But it does help to an extent. So, it’s all really pretty crazy.

The main needs of the security world (see right-hand image) at this stage are: we need better situational awareness. And a lot of people are arguing that the only way to do this is to improve big data analytics, because if you’ve ever set on the side of a sys administrator, you can’t watch the logs in real time. There’s tools to basically help you analyze these logs and all the events going in real time for that network. And so these tools are pretty helpful, but they’re not that great. So there need to be better tools to analyze all the huge, massive data that is going on in the network in order to be more situationally aware at the given moment. You can easily understand how that problem has worsened the larger your network gets.

There’s also a big strive for having more threat intelligence. There’s a lot of companies actually that sell consulting for threat intelligence. Hundreds, if not thousands of exploits come out, and vulnerabilities come out every year, but only a dozen or two dozen are actually commonly used by the majority of attackers for mainly their reliability, ease of use and for what they provide. Some vulnerabilities only allow denial-of-service. Some other vulnerabilities allow remote code execution and privilege escalation. They’re not all the same, so instead of worrying and saying: “Oh my god, everything is so insecure”, basically, a consulting company is going to say: “No, look, you just have to really pay attention to these main ones, secure against these ones, and you mitigate 90% of your risk. And you can go about resuming normal code auditing, penetration testing and security assessment”.

Another big need of the security world is that there needs to be more harmony on cyber law. I don’t know how well universal intelligence IP right laws are going to work, and people, especially policy makers, need to be more aware of how the Internet of things is really going to impact the future.

a nice and well described article about cyber warfare.thanks for the historic information. however, would like to know about sectors may be affected with critical analysis.

regards

Zillur