Damon McCoy, Assistant Professor at George Mason University’s Computer Science Department, gives a great presentation at USENIX Security Symposium dissecting the business model of spam-driven online pharmaceutical industry.

Damon McCoy, Assistant Professor at George Mason University’s Computer Science Department, gives a great presentation at USENIX Security Symposium dissecting the business model of spam-driven online pharmaceutical industry.

I am going to be presenting our work on PharmaLeaks, or as I like to call it: ‘Rogue Pharmacy Economics 101’. We collaborated with a good number of people. The interesting collaborator is Brian Krebs. He is a journalist. He does a lot of investigative reporting on cyber crime and he focuses a lot on the pharmacy affiliate program business model. If you are interested in this subject, he maintains a very interesting blog that you should read to get even more details on this subject.

Let me give you quickly some context as to what these online pharmaceutical drug programs are. So, perhaps anyone who has clicked on a spam advertising link, there is a high probability that you’ve seen a storefront similar to this one (see screenshot), advertising online pharmaceuticals, mostly ED (erectile dysfunction) pills, and all without prescriptions and at discounted prices.

Most people have probably seen this but let me take a step back and show you what are the actual players involved in this economy.

So, there are three main players in this economy. There is the User, which is the potential customer; there is the Affiliate Marketer, which is typically is a spammer; and there is the affiliate program. And let me go into a concrete example of business interaction between these three parties.

Initially, what happens is that the affiliate marketer perhaps gets the user to see some kind of spam advertisement that includes some kind of link. It includes some kind of enticement of cheap drugs, no prescription required, to get the user to click on this. If the user is actually interested in perhaps buying these pharmaceuticals, clicks on it, they’ll be delivered that template that I showed you in the original slide.

And the user can interact with this template just as with the normal e-commerce site. There is a wide selection of drugs there, they can select their drugs. If they indeed want to purchase some drugs from this site, then at this point of time the relationship switches from the affiliate, whose job is to track customers, to the affiliate program, whose job is to actually monetize the customers and turn them into money.

At this point, the spammer fades out, the affiliate program steps in. And if the user decides to purchase, this purchase typically happens with credit cards. The user gives the credit card details to the affiliate program (see image). And the affiliate program, as you will see in the rest of this presentation, actually operates much like a business.

Their job is to process these credit cards, and then they’ll actually deliver some products that you ordered. So this isn’t a complete scam: these pharmacy affiliate programs that I will show you operate much like a business. And they are very interested in keeping their customers happy and satisfied because these customers are paying with credit cards. If they are not satisfied customers, they are going to charge back and this affiliate program will be shortly out of business. And as I will show from the economics, these affiliate programs are in it for the long haul, and they want to scale their business to large millions of dollars. So, it’s not in their interest to have dissatisfied customers.

Quickly here, the pharmaceutical affiliate business. This is one of the largest sectors of how to monetize spam. As shown at our previous talk 2 years ago in Auckland, large fraction of the spam emails map back to one of these kinds of online pharmaceutical programs. Spammers see this is a very lucrative way to monetize spam.

We’ve come to the approach of fighting spam, which is very important to actually understand the business of the spammers, and to try and identify potentially fragile parts of their business that we can maybe undermine to make them much less profitable, or perhaps drive them completely out of business, if we can disrupt some fragile part of their business.

So, the goals of this study are to characterize the key aspects of these pharmaceutical affiliate programs. Let me just quickly go more concretely into what exactly these pharmaceutical affiliate programs are and what they are responsible for, for people that are unfamiliar with them.

They also need to maintain good relationships with suppliers and shippers to deliver their goods to keep the customers happy, to stay in business. They also need to maintain relationships with payment processors. This is probably one of the key components of their business. If one of these relationships with their payment providers breaks, they can no longer accept payments, they are no longer making revenue, they can no longer pay the rest of the people, and their business will quickly fade, they’ll go out of business. As I said, these affiliate programs operate much like any other businesses do.

– affiliates (spammers)

– suppliers and shippers

– payment processors

In previous studies, a lot of people, including our group, have inferred just small little parts of these online businesses. And it’s always been unclear as to how accurate these inferences are, and we have only got tiny little pieces of the businesses that we can infer.

However, in PharmaLeaks we have had fortuitous events of getting a large corpus of actual ground truth data that’s been leaked from a few subsets of these online pharmaceutical programs. And with this ground truth data we can do a far more detailed analysis than any other analysis of how these businesses operate, and the dynamics of these three key players: the customers, the affiliates, and the affiliate programs; and understand a lot how this business functions, and understand the fragile parts of their business deeper.

So, let me just quickly go into detail about what this leaked corpus looks like. As part of this leaked data set, we have numerous leaked sources of financial and operational information from three separate affiliate programs. A lot of this information leaked because of the ongoing rivalry between two of these spam operators, and they tend to get pissed off of each other.

They will somehow obtain some information, they will leak it sometimes widely on the Internet, sometimes a little bit less broadly to a large set of law enforcement and reporters, just to say that the other people are really bad and you should lock them up and put them out of business. And then, in retaliation, the other operator will in turn do the same thing to them.

So, we received the windfall of this kind of rivalry. And as part of this we have the back-end database, which includes order information, transactional information, a very rich set of information on the GlavMed / SpamIt programs, which are two of the larger online affiliate programs, according to when we did our analysis of spam and linked it back to the different pharmaceutical affiliate programs.

We also have chat logs from the operators of the GlavMed / SpamIt programs which, again, give us a lot of metadata and insight into how their business operates. We have a more restricted set of transactional information from the Rx-Promotion affiliate program – again, an extremely major online affiliate program that constituted a large portion of spam while they were operating. And we also have extremely fine-grained revenue and cost structure information for Rx-Promotion.

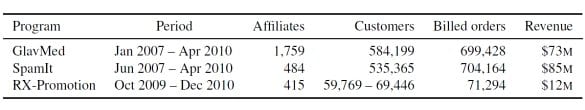

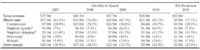

Just a quick summary of this data: it encompasses over $185M in revenue of purchases. It encompasses over a million customers, over 1.5 million orders, and over 2,600 affiliates (see below).

During our analysis of this data, we realized that GlavMed has often denied that they are the operator of SpamIt, however by our analysis of the databases of GlavMed / SpamIt, we realized these two are operated by the same people. And also, Rx-Promotion transactional data, as I said, is somewhat limited. It is limited to the US customers. Luckily, US customers make up the majority of all customers. So we get a fairly detailed picture of Rx-Promotion from this limited transactional data.

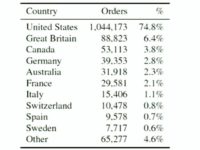

Now let’s delve into the first player in this spam economy, which is the customer. So, a quick rundown of the demographics of their customer base (see stats to the left). As you can see, majority of it is from the US, then a smattering from Western Europe, Canada and Australia. All told, 95% of the customers are from those four locations. This largely confirms what we presented last year when we inferred from some weblogs the composition and the demographics of the customers.

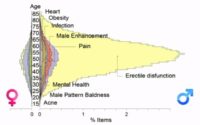

So, now that we know the demographics of the customers, let’s look at what these customers are buying. As this ironically shaped graph shows (see image to the right), as you might suspect, they don’t put the Viagra and the Cialis on the front page for no particular reason – that is in fact the large share of what they are selling, the ED pills. And they are selling them to largely male demographic.

They also have a large formulary of other drugs they sell, and they do sell a small fraction of those things also. It depends on the formulary, some pharmacies sell more other drugs and less ED depending on the formulary that they carry, but this is the case for SpamIt and GlavMed. And in fact, 75% of the orders and 80% of the revenue for the GlavMed / SpamIt program are derived from the ED medications.

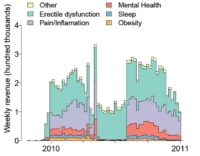

Now let’s take a quick look at Rx-Promotion which had a slightly different formulary. Here is the revenue structure for Rx-Promotion (see graph). We couldn’t get the demographics: the dataset wasn’t rich enough to figure out the demographics for the Rx-Promotion.

Here you can see this kind of interesting, kind of tooth graph. As you can see, they derive a little bit more of their revenue from the pain medications. They derive a lot of their revenue from the ED. You can see the X axis, which is time moving forward, and the Y axis being their revenue numbers derived from each product, but in the middle of this graph you can see this sharp falloff in their revenue.

This sharp revenue falloff was caused by them losing a relationship with one of their payment processors that accepted VISA payments for a certain class of drugs. You can see the class of drugs that fell out of their revenue. And as you can see, this disruption in their payment processing caused their revenue to almost half at this period. At the beginning of this disruption they in fact became unprofitable, and it took them about two to three months to re-establish this payment processing relationship.

As you can see, when a program incurs this kind of payment processing disruption, this has a huge negative impact on the profitability of these businesses. This comes from some of our findings when we mapped out the banking relationships between these programs. This is indeed a fragile, hard-to-replace portion of their business.

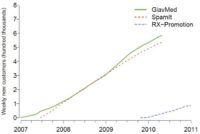

Now that we’ve looked at product demand and demographics, let’s take a look at how these programs attract new customers (see graph). On the Y axis is the number of new customers that the program attracts by the hundred thousands, on the X axis is time moving on.

GlavMed / SpamIt have a very similar-shaped curve. It’s somewhat regular; they have a consistently new stream of customers coming in. And Rx-Promotion has a similar kind of linear trend of this constant stream of new customers coming in. And if we you count the numbers, the GlavMed / SpamIt program attracts about 3,500 new customers per week, and Rx-Promotion program attracts about 1,500 new customers per week.

I think this is possibly the most interesting result of this study. It is interesting because it shows that this market for online pharmaceuticals isn’t saturated. In fact, they are constantly gaining new customers at this rate. And I think this explains a lot the behavior of the affiliates and spammers, and why the spammers want to make sure that everyone on the entire US gets spam email advertising these pharmaceuticals, because it’s effective and it works, and they continually gain new customers doing this kind of behavior. This kind of behavior is profitable for the affiliates, so they are going to continue to do this kind of behavior because, indeed, this market isn’t saturated, they are constantly finding new streams of customers, and that kind of advertising works.

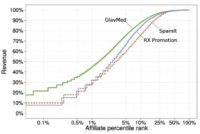

Now that we’ve looked at the customers, let’s switch to the affiliates and see how they operate. Here is a breakdown of the revenue of the affiliates (see graph). On the Y axis is the percentage of revenue for the affiliate program that each affiliate contributes, and on the X axis is the percentage of affiliates that takes to achieve that percentage of revenue for the affiliate program.

As you can see form the X axis, just like in every other kind of multi-level marketing schemes, there is a small number of very successful affiliates, and there is a large number of affiliates that are not so successful. A lot of them just completely fail at trying to be affiliates for these online pharmaceutical markets.

And in fact, 10% of the affiliates account for about 80% of the total program revenue across all three programs. So, this is another interesting finding, it seems that there is just a small number of very successful affiliates driving a lot of the sales. So, if we could potentially find some way, possibly legally, to disrupt this 10% of the power affiliates that do a really good job of earning for these programs, perhaps that’s another way to undermine them and cause them to be far less profitable.

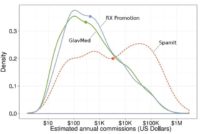

Let’s look at these affiliate commissions in a slightly different way (see graph). On the Y axis is the density, on the X axis is the estimated annual commission rate for the different affiliates. So, GlavMed and Rx-Promotion have kind of similar curves here, and SpamIt has a kind of bimodal distribution. By the way, the little dots on the lines are the median annual income for affiliates. As you can see, for GlavMed and Rx-Promotion it’s about $350. For SpamIt, with the bimodal distribution, it’s about $500 in one of the modes, and about $30,000 in the other mode.

Let me explain why GlavMed and Rx-Promotion follow mostly the same curve. Their type of affiliate program is termed as Open Affiliate Program, meaning that they don’t really do a lot of screening for their affiliates. They’ll let pretty much anyone walk in and try to be an affiliate for them. And that’s somewhat the beauty of the affiliate program structure: the affiliate program doesn’t really incur much cost in allowing more affiliates to join the program because the affiliates only get paid on the commission basis. So, if the affiliate is unsuccessful they don’t get paid, there is no real risk associated with bringing new affiliates.

And the affiliate program has this problem that it is hard to tell a priori who are the good affiliates, who are the good spammers that will drive lots of traffic to your site. So, by being an open program you can just let them all try their hand at being affiliates for your program. A lot of them, as this graph shows, are going to fail. Some of them at the long tail are going to succeed brilliantly.

And SpamIt was more of what they term a Closed Program, where they did a lot more background check for due diligence. Either you had to be avowed by someone else who was a good affiliate, or you had to have some kind of record of being a good affiliate yourself. And indeed, this shows that that does a better job of attracting the power affiliates to your program. But again, still it’s difficult a priori to tell who are going to be the successful affiliates for your program even when you do this due diligence screening. These are just the quick numbers, and as you can see there is this large failure rate as in most multi-level marketing schemes.

Strategies for Spamming

Now that we’ve looked at some general numbers on affiliates, let’s look at some of the top earning affiliates here. So, on the high end of things, let’s look at some of the schemes that these top earning affiliates use to be successful spammers.

An obvious one to think of is run a large bot network and spread a whole bunch of spam. In fact, the operator of Rustock – we identified him within SpamIt dataset – made close to 2 million dollars by operating Rustock and sending out spam for the GlavMed / SpamIt program. That indeed is a very good way of becoming a successful marketer – to run a large bot network.

Let’s look into another way of doing it – we isolated an affiliate named Scorrp2. Scorrp2 earned about 3 million dollars. However, Scorrp2, from an analysis of the referer headers, appears to have rented out multiple bot networks, and perhaps rented out or perhaps bought code from different botnet writers, and maybe operated his own version of each one of these bot networks, it’s somewhat unclear. But he didn’t operate just one bot network like the Rustock people.

However, if you dig deeper and do a more in-depth analysis, you can see that actually the largest overall earner, of all of our data, was an affiliate named ‘webplanet’. And this affiliate appears to have not used spam emails but in fact used web-based advertising to earn about 4.6 million dollars.

So, it is one of these interesting questions that I think of: what is the optimal strategy for spamming? Also, this is gross revenue for the spammers, and unfortunately our leaked dataset doesn’t offer much insight into what are the actual profits of these spammers, because in fact these spammers have a lot of the costs themselves. As we will show you in the case of the affiliate programs, they are not making all this money as pure profit, there are some expenses incurred in spamming this much. But unfortunately the datasets that we have don’t answer these questions.

As you can see, these top earners earned quite a bit of money, and they in fact earned the larger share of each individual sale. However, the affiliate programs, if they are very successful, in fact can earn more by taking a smaller portion of each sale over all of the sales from their affiliate program than the individual affiliates.

Direct and Indirect Costs

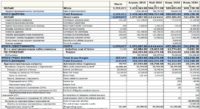

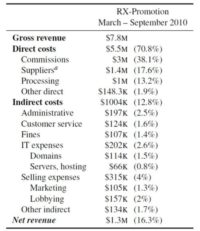

As I said, the affiliate programs operate very much like a business. Here is a spreadsheet from Rx-Promotion that has their fine-grained accounting data (see image). This accounting data actually conforms to international financial accounting records, and as you can see it is extremely detailed. It gives us a very fine-grained look at their profits, their gross revenue, and their costs. So, using this and other transactional data, we can get a very good handle on the cost structure of these affiliate programs.

So, very quickly let’s go over to the direct costs. These are costs that occur every time that a purchase occurs. As I said before, the affiliates earn the largest portion of each individual sale. Their commissions range from 30% to 45%. If it’s a very successful affiliate they can negotiate larger commission rates, which shows that there is a limited number of these very successful affiliates, and the affiliate programs compete by offering them larger and larger portions of the sale as commissions. In the chat logs we can see the different operators competing for these top affiliates and cutting deals to give them more and more commissions.

Next is the suppliers. The interesting thing here is that shipping actually is the larger cost than the actual cost of the drugs. So, shipping is about 11%-12% of their cost, suppliers – about 6%-7% of their cost, in total it is about 18% of their cost. And then processing – paying to process the VISA cards – is about 10% of their cost. And their gross margin, this is probably a very optimistic estimate of their profits, is about 30%.

However, as I will show you in the next slide, these are just the direct costs, they also have indirect costs associated with their business. If we look at some of the more fine-grained cost structure of the Rx-Promotion program (see image), we can see that they have direct costs of about 70%, but they also have these indirect costs of about 13% of their revenues.

Indirect costs are things like people’s salaries, there are things like lobbying their governments, marketing. And marketing in this sense means attracting affiliates to be part of their program. A lot of these costs are somewhat fixed. Even though GlavMed was doing a lot more sales than Rx-Promotion, indirect costs seem to be the same across these programs, suggesting that they are somewhat fixed. And again, arguments that they want to have this economy of scale are to try and negate out these indirect costs.

So, all this leaves them with probably a more accurate estimate of about 16% of the profit that they are actually making off this business. And this correlates with the chat logs where the GlavMed / SpamIt operators report about 10%-20% when there are talking with their affiliate about their cost structure.

Payment Service Providers

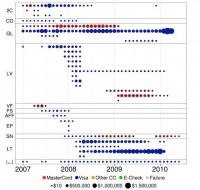

So, now that we’ve looked at the cost structure, let’s look at the payment service providers (see image). Quickly on how to read these figures: each one of the abbreviations represents a different payment service provider. Each row represents a different account that they have established with that payment service provider. Sometimes they established multiple accounts to get redundancy – in case one account is shut down they have other accounts to fall back on.

As you can see from this graph, there are very few of these over the course of more than three years of data that we have. The size of each dot represents how much revenue was processed through each one of these accounts. The larger the dot, the more revenue was processed to that account.

So, quickly to point out some events. In that line right there this kind of represents the souring of the relationship with LV. And because of this relationship souring with LV, who they had used to process the majority of their payments, they had to push more of their processing onto LT and GL, which were the two other main payment service providers that they had.

If you look more forward in time, you can see that the relationship completely soured with LV, and soured with LT, and they were left with only a single payment processor GL that they had to use to process all their transactions. And then, if we look forward in time, their relationship with GL sours, and just like in the case with Rx-Promotion when they lost their bank relationships, their revenue sharply declined.

Extending further out, we have metadata that shows that they tried to deal with another payment service provider. They agreed to much less favorable terms, they had to pay much more than the 10% typically required. And thus they’re becoming less and less profitable because of these disruptions in their payment processing services, this is becoming more and more of a direct cost to them. According to our study, these three payment service providers accounted for about 84% of all the transactions.

Let me give you an epilogue on where these programs stand currently. About several weeks ago on the GlavMed forum the operator posted a message; I don’t speak very good Russian, luckily one of my co-authors translated this for me. So, just quickly, it says they are having problems with their processing, they can’t accept any new orders and consequently they have to cease operations until they find a new payment service provider that will process their transactions.

A similar thing happened to Rx-Promotion. They had only a single payment service provider, their relationship soured and in fact they are out of business currently.

Summary

So, just to conclude, a small number of the advertising affiliates generate most of the revenue. This market is not saturated. The affiliate programs have substantial costs. They have a very thin profit margin. If things go badly their payment service provider squeezes them for more share of the money, which drives them to be less and less profitable. When there are financial disruptions their indirect costs become a larger burden on them and they become unprofitable. And only three payment providers were responsible for a majority of the transactions for GlavMed. So, indeed, this is a fragile part of their business that, once disrupted, costs them a lot of headaches.