Jason Healey is the director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative of the Atlantic Council, focusing on international cooperation, competition and conflict in cyberspace.

Jason Healey is the director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative of the Atlantic Council, focusing on international cooperation, competition and conflict in cyberspace.

He also is a board member of the Cyber Conflict Studies Association and lecturer in cyber policy at Georgetown University.

He co-authored the book Cyber Security Policy Guidebook (2012) and is the editor of A Fierce Domain, Cyber Conflict 1986 to 2012 (2013), the first book ever on cyber conflict history.

Jason has unique experience working issues of cyber conflict and security spanning fifteen years across the public and private sectors. Jason has previously been vice president for Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong, where he built their Asia-wide crisis management and incident response capabilities and managed business continuity. Prior to that, as Director for Cyber Infrastructure Protection at the White House, he helped advise the President and coordinated US efforts to secure US cyberspace and critical infrastructure.

Starting his career in the United States Air Force, Jason earned two Meritorious Service Medals for his work in cyber operations at Headquarters Air Force at the Pentagon and as a founding member of the Joint Task Force-Computer Network Defense, the world’s first joint cyber warfighting unit.

He has degrees from the United States Air Force Academy (political science), Johns Hopkins University (liberal arts) and James Madison University (information security).

– Jason, during your Black Hat talk you pointed out that we are not learning from past cyber threats and conflicts. Who is not learning exactly? Seems private sector does learn and invests in building stronger networks, and it is the government that mostly doesn’t learn?

– In particular, it is government policymakers who are not. The “private sector” is a bit too broad to use here. Some executives in some sectors understand, but even this is mostly focused on the very narrow. Very few people in any sector are looking at the broader scale of cyber conflicts, rather than smaller tactical engagements.

– How do we start learning from the past? Do you have a specific approach?

– The US government, especially the military, need to focus on looking at the history of cyber conflicts. Studying these as an aspect of military history is the best way to learn past lessons.

In other areas of national security, newly hired people learn their field through the vicarious experience of those that have gone before. Understanding history is the main way to turn the experience of the past generations into cumulative knowledge, such as by teaching military officers the implications of Gettysburg, Inchon, Trafalgar, or MIG Alley.

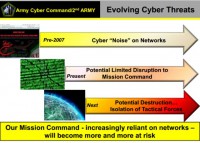

– Cyber conflict’s scope is changing gradually, but within cyber conflicts, where do you see the most changes?

– In your opinion what are the top 3 cyber security actions America’s policymakers should take?

– The most important thing is to realize there is very little the government can do. Nearly every conflict has been decisively resolved not by government, but by coordinated action by non-state actors. Therefore, it should be US policy to do everything it can do to recognize the central role of non-state actors, support them, and use the existing governance mechanisms.

– America tried both, why exactly did we get no results from the bottom–up approach?

– We’ve been too half-hearted. The relationship with the private sector isn’t a “partnership” but one where the government must use a ‘non-state centric’ strategy.

– What do you expect from Cyber 9/12 Student Challenge?

– What are the Cyber Statecraft Initiative’s activities in the sphere of open source intelligence?

– Nothing interesting.

– Where and when do you expect cyber conflicts to appear resulting in great real damages?

– Fifteen years ago, we said the big attack (the ‘cyber Pearl Harbor’) would be in “five years.” Ten years ago, we said again, “five years.” Today, we still say “five years.” Now it is likely the big attack will happen, yes, in five years.

– Are terrorist groups already capable of performing a prolonged massive cyber disruption with great bad consequences or is it still the prerogative of nation states?

– Nope, still states!

– Between what players will we see the increase in cyber conflicts – between nation states or private companies or other groups, maybe terrorists or criminals?

– Everyone is getting ever more involved. The most worrying though will be the continuing trend of nations, the only groups with true offensive capability.

– Is there an arms race in cyber space now?

– No, not really. There is certainly a massive amount of very high-grade capabilities available on the open market. This is fed by, and feeds, governments. But I’d reserve ‘arms race’ for something like this. Arms race implies a two-actor field, or at least only a few actors. There are so many actors involved in the offensive cyber field that calling it a race is misleading and distracts from noticing it is a scramble.

– Are there countries which focus more on cyber rather than on traditional weapons?

– Can you name unsuccessful cyber attacks performed by nations and consequences of such attacks?

– Easier to note the successful attacks, like Stuxnet.

– Could you name a cyber conflict success story where government did show it was learning from history lessons, maybe an international example?

– Certainly Estonia has! Though it has been portrayed as a cyber disaster, it was actually a tactical and strategic defeat for the ethnic Russian attackers: the Estonian government was not coerced, and the statue was still moved. The attacks did not result in long-term damage or a negative impact to the economy while staining Russia’s international reputation. Indeed, the incident may have led to an overall increase in Estonian GDP, as its president, Toomas Ilves, made the incident a cause célèbre. His focus ensured that Estonia, NATO, and other nations were aware of the implications of cyber conflict, the next of which was not long in coming.