The entry reflects an extremely interesting insight into the peculiarities of general security perception in Eastern Asia, presented by the well-known German computer security specialist Paul Sebastian Ziegler at Hack In The Box 2012 Conference.

Today’s talk is entitled “I Honorably Assure You: It Is Secure. Hacking in the Far East”. Now, before we get started on that topic, there is one thing we have to get out of the way, and in case you’ve heard me talking before, you know what’s coming next, because unless I tell you who I am, you will not want to really hear what I have to say. But if I take too long to tell you who I am, you won’t be interested anyway. So, here’s my brief introduction.

Introduction

Hello, my name is Paul Sebastian Ziegler and I am a professional pentester. I live in Tokyo, but I work and travel all over Asia, where I enjoy the English that only Asia can come up with, and I also massively enjoy always finding new comparisons to describe the current state of the security community.

Hello, my name is Paul Sebastian Ziegler and I am a professional pentester. I live in Tokyo, but I work and travel all over Asia, where I enjoy the English that only Asia can come up with, and I also massively enjoy always finding new comparisons to describe the current state of the security community.

If there’s anything else you would like to know, or if you’re feeling stalkerish you can check out observed.de, which is where I keep links to most of the papers, most of the slides, just in case you miss one.

So, before we begin, when I designed this speech I did not quite expect how this situation in Eastern Asia would evolve over the last couple of weeks.

So, before we begin, when I designed this speech I did not quite expect how this situation in Eastern Asia would evolve over the last couple of weeks.

So, there is this weird thing going on right now, where even though Eastern Asian countries share up to 80% of their culture, and their writing, and lots of their language, there’s a lot of hate going on over issues that really have nothing to do with what they’re supposed to be.

Now, from a foreigner’s perspective – and I’m not going to take a stance on this – it looks like everyone involved has gone crazy. I don’t know what country you’re from and if you’re in the room, I don’t know what country you’re from if you’re watching this on a video later on, or if you’re reading about this, or just looking at the slides. But if any of the things I’m going to say is going to offend you, then please be offended by the ignorant white guy. Don’t be offended by any country you attribute myself to. So, in a nutshell, please, way less of hate, and way more of that (see right-hand image), because I think we can all agree that’s really cool Asian stuff.

Now, from a foreigner’s perspective – and I’m not going to take a stance on this – it looks like everyone involved has gone crazy. I don’t know what country you’re from and if you’re in the room, I don’t know what country you’re from if you’re watching this on a video later on, or if you’re reading about this, or just looking at the slides. But if any of the things I’m going to say is going to offend you, then please be offended by the ignorant white guy. Don’t be offended by any country you attribute myself to. So, in a nutshell, please, way less of hate, and way more of that (see right-hand image), because I think we can all agree that’s really cool Asian stuff.

Well then…

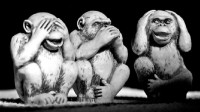

We’re going to start off here with one of the basic concepts in Eastern Asia, and I’m going to call it by its Japanese name, but there is a similar concept in Confucianism, it’s called the Three Wise Monkeys (see image). What do they do? The picture has kind of made it clear: the Three Wise Monkeys is a philosophical approach of how you should live your life. Namely, you should see no evil, you should hear no evil, and you should speak no evil.

We’re going to start off here with one of the basic concepts in Eastern Asia, and I’m going to call it by its Japanese name, but there is a similar concept in Confucianism, it’s called the Three Wise Monkeys (see image). What do they do? The picture has kind of made it clear: the Three Wise Monkeys is a philosophical approach of how you should live your life. Namely, you should see no evil, you should hear no evil, and you should speak no evil.

Now, even though the light is shining in my face, I can kind of see that some of you are wondering: “Ok, why the f**k is this guy talking about philosophy in a hacking talk?” Well, because it makes it kind of interesting to hack in Japan, because people will do whatever they can to ignore you.

Let me give you an example: this is a picture I took a few weeks back in a big public park in Tokyo (right-hand pic). As you can see in the background, no one cares. So, even though there’s five guys dressed up as Power Rangers performing all the moves, people don’t ask them what they’re doing, people don’t go away, people just pretend they’re not there, following the: “I don’t see anything, and if I don’t say anything or hear anything, it’s going to go away on its own.”

Let me give you an example: this is a picture I took a few weeks back in a big public park in Tokyo (right-hand pic). As you can see in the background, no one cares. So, even though there’s five guys dressed up as Power Rangers performing all the moves, people don’t ask them what they’re doing, people don’t go away, people just pretend they’re not there, following the: “I don’t see anything, and if I don’t say anything or hear anything, it’s going to go away on its own.”

So, one of the results of that is, unless you force people to acknowledge what they’re doing, they’re just going to try to ignore you, whether that is hacking or pentesting, or just being weird.

Looking for the Border of Indifference

So, a couple of years back I took a friend aside and we tried to find out just where the limit to that phenomenon is. We really wanted to figure out how far we can go in public in Japan with hacking before someone would intervene.

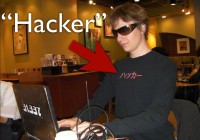

So, this is a Starbucks in Tokyo, and it’s a normal laptop, and my normal suit back then (see image to the left). Unfortunately, you cannot really see the monitor right now, it was running Wireshark wildly running through stuff, not because it was really important, but because that comes closest to what most people who have seen the Matrix movies think hacking is all about, right? Lots of scary characters flashing by your screen.

So, this is a Starbucks in Tokyo, and it’s a normal laptop, and my normal suit back then (see image to the left). Unfortunately, you cannot really see the monitor right now, it was running Wireshark wildly running through stuff, not because it was really important, but because that comes closest to what most people who have seen the Matrix movies think hacking is all about, right? Lots of scary characters flashing by your screen.

So, sitting in a public café running Wireshark probably won’t get you any issues either in Europe or in the States, so we took this and we kind of changed it a little notch. Now, I’m not sure how good the resolution is, the T-shirt says: “I read your email.” Still no one really reacted, so we added the sunglasses, and since that didn’t do it, we replaced the small black ThinkPad with a huge silver ThinkPad with a sticker on it. And since that didn’t get a reaction either, we then added a 23 dB omnidirectional antenna, connected by a coaxial cable into a PCMCIA card (see image).

So, sitting in a public café running Wireshark probably won’t get you any issues either in Europe or in the States, so we took this and we kind of changed it a little notch. Now, I’m not sure how good the resolution is, the T-shirt says: “I read your email.” Still no one really reacted, so we added the sunglasses, and since that didn’t do it, we replaced the small black ThinkPad with a huge silver ThinkPad with a sticker on it. And since that didn’t get a reaction either, we then added a 23 dB omnidirectional antenna, connected by a coaxial cable into a PCMCIA card (see image).

Now, the more security savvy among you may notice a couple of indicators that something bad is going on in this picture: you know, the sunglasses, the shirt, the laptop, and the antenna.

But we kind of figured: “Ok, these people are Japanese, they may not be able to read the English hint we left them, and maybe some of the symbols just don’t work the same way around here.” So, luckily, there’s some really great stores in Japan that will print whatever you want on a T-shirt, so we made this, (Slide 31) this says “Hacker” in Japanese (see left-hand image).

But we kind of figured: “Ok, these people are Japanese, they may not be able to read the English hint we left them, and maybe some of the symbols just don’t work the same way around here.” So, luckily, there’s some really great stores in Japan that will print whatever you want on a T-shirt, so we made this, (Slide 31) this says “Hacker” in Japanese (see left-hand image).

And after we sat there wearing this and taking a couple of pictures with this shirt on, about 3 minutes in, finally a Starbucks staff employee walks up to us and he goes, if we translate it into English: “Well, I humbly apologize, but I must ask you to kindly leave.” And we were thrilled, we were kind of like: “Done it! We have found the border; we have found how far we can go in Japan before they kick us out.” Yeah, the only problem is the reason we got kicked out had nothing to do with all of this stuff that I’ve just shown you. The reason we got kicked out of Starbucks – I’m not making this up – is it’s not allowed to take pictures in Starbucks.

So, I’m not sure where the boundary is – I haven’t found it yet, and I have been working in Japan for a really long time, but there doesn’t seem to be one.

For every element I’m going to point out to you today, after this we’re going to look at the exploitation vector, because that’s what makes it interesting. So, for this particular exploitation vector: if you’re going to start doing pentests in Japan or Japanese companies, or if you’re a black hat guy and you’re just going to run attacks in Japan, you can basically screw all of your covertness, because no one is going to care anyway. Just make sure you’re not on camera, but people on the street are not going to interfere. For all they care, you can have a cable going into the hotel’s PBX system – they won’t stop you.

So, you are sitting there and people won’t stop you, but you still have this feeling that they can kind of see you, right? That’s uncomfortable. So, it would be really nice if we had one of these (see right-hand image). Historical evidence abounds that they used to be very popular in Japan and all over Asia, and they’re even more popular today, you can see them in the movies – apparently, there is a huge market around them, because you can also buy them on Amazon for only $400, that sounds like a good deal. Unfortunately, as further review revealed, they don’t seem to be very effective.

So, you are sitting there and people won’t stop you, but you still have this feeling that they can kind of see you, right? That’s uncomfortable. So, it would be really nice if we had one of these (see right-hand image). Historical evidence abounds that they used to be very popular in Japan and all over Asia, and they’re even more popular today, you can see them in the movies – apparently, there is a huge market around them, because you can also buy them on Amazon for only $400, that sounds like a good deal. Unfortunately, as further review revealed, they don’t seem to be very effective.

Clothing Does Matter

So, what if I told you that as long as you stay within Japan, there is actually a cloaking device that will make you absolutely invisible to ticket gate people, police, people who may talk to you for social violations, auditors, home security? There is one, you can buy it. You can buy it anywhere in the world. Here’s mine (see left-hand image).

So, what if I told you that as long as you stay within Japan, there is actually a cloaking device that will make you absolutely invisible to ticket gate people, police, people who may talk to you for social violations, auditors, home security? There is one, you can buy it. You can buy it anywhere in the world. Here’s mine (see left-hand image).

If you put on this suit in Japan, you basically become invisible. When I say invisible, let me give you some numbers for this. So, badge requirements, corporate badges, going in anywhere, conference badges, anything like that – no one is going to ask you. Security will not stop you if you’re the guy wearing a suit. If they do stop you, come back 30 minutes later, pull out a cell phone and talk really loud in English – and suddenly you’re too scary for anyone to approach.

In my personal case, it reduced the number of random police ID checks from once a month to never. In Japan police are actually allowed, if you’re a foreigner, to check for your foreigner registration ID, and it’s usually a quick process, but still it keeps bothering you. And, virtually, that’s a getaway with any social violation you want. So, if you ever wanted to stand in a public place and scream loudly, then wear a suit.

This also works in South Korea, interestingly, but it kind of works differently in South Korea. When you go to South Korea, the suit will really affect you as well. However, I wouldn’t really call it the invisibility cloak; I would call it the Honor Cloak. Because what is does is suddenly – and this is mostly for males, for girls this doesn’t particularly work, but foreign girls don’t really have an issue in Korea to begin with – people in restaurants will start giving you service, and when I say service, I mean anything that goes beyond “huh?” and “huh.”

It will also lead to the natives being about thrice as willing to try to communicate with you in any language they may be able to speak, instead of screaming for the next person to come to the counter at Starbucks. Strangers will take you to locations and carry your stuff. And this sounds scary, but this has happened to me literally every time I visited Korea in a suit.

So, what happens is if you walk outside and you’re wearing a T-shirt and you go: “Yeah, I don’t know where this is, can you help me?” – people have this tendency to do the monkeys and just turn around and walk away. If you wear a suit, they will take you there, because they can’t explain it to you, so they just literally take your hand and they’ll walk you wherever it is. The other thing that happened repeatedly is that you’re standing at the airport and you have your suitcases, and you leave one downstairs because you can’t really carry everything at once, and some random guy will just walk up, take your suitcase, carry it, say: “Have a nice day,” and walk off.

This has never happened without a suit; it will happen with a suit. And the last thing, or the second to last thing, is that you can actually get a taxi as a single foreign white male. If you’re not wearing a suit, this may take up to 20 minutes. And what’s really weird is that the taxi drivers will actually drop you off where you want to go. Some of your faces are saying: “Yeah, but that’s kind of the purpose of a taxi.”

In South Korea, at least in Seoul, what happens if you’re a foreigner is they won’t take you where you want to go, they will take you to a near intersection that they see fit and they’ll kick you out, because, I quote: “I’m not a racist, but you’re a foreigner, and I’m just not quite sure what you’re going to do.” So, in case you wear a suit in Korea, as a male, it seems like you’re in a completely different country compared to not, just wearing civil clothing.

The Swarm Effect

Now, we’ve seen it and we have these weird effects when you go to Korea and Japan with suits, but why is that? There’s two things in play. Number 1 is the Swarm Effect, which basically is something common in every animal, humans included, which means: “If something looks like me and if I don’t stand out of the group, I’m going to be integrated and people are just going to forget about me, and they’re going to be nicer because I look like them.”

Here’s what a typical morning commute looks like in Japan (right-hand image). Notice the pattern. And here’s the same thing in Korea, which is a church session – again, suits (image below).

Here’s what a typical morning commute looks like in Japan (right-hand image). Notice the pattern. And here’s the same thing in Korea, which is a church session – again, suits (image below).

So, you’re wearing a suit – you’re showing off your integration. You can’t really wear the traditional clothing, because no one wears those anymore. But if you wear a suit, you look like everyone else, therefore you do not appear threatening.

So, you’re wearing a suit – you’re showing off your integration. You can’t really wear the traditional clothing, because no one wears those anymore. But if you wear a suit, you look like everyone else, therefore you do not appear threatening.

The Class Effect

Even a more important thing is the Class Effect. Now, this is not as it may seem about classes, like lower class, middle class, upper class – you can forget about that. From the perspective of Eastern Asians, from what I’ve seen, there are three classes of foreigners. There’s military people – it’s class 1. If you’re grouped in military, you’re a big guy, you look like a military guy, you talk like a military guy – basically, you’re screwed, because military is scary.

In all the newspapers for some reason, if a military guy in Roppongi Hills shows up and beats someone, you can be sure it’s going to be in the newspaper the next day. So, if you’re grouped in the military, you’re scary, you’re kind of shady, and no country in the world really likes a foreign military on its ground, no matter what we pretend or no matter how practical it may be at the moment.

The second category, in a nutshell, are English teachers. And when I say English teachers, it could be any kind of other foreign language, it could be a French teacher if you’re from France. If you fall in there, you’re not going to be scary, you’re going to be ok. The problem is that from the perspective of natives you’re some dude, and they’re usually in their mid to late twenties or early thirties; you’re some guy in that age range whose only major life accomplishment after this point has been to master the native tongue. So, you’re not particularly considered a good match for any specific occasion.

And the last of the three categories is business. Now, when I say business I don’t mean people who actually do business, I mean people who are either skilled workers who have money, or people who are in any way involved in actual work that requires some sort of skill or some sort of investment, and you really want to fall into that group. Why? Well, first off, you’re not really scary and there’s not many negative stories told about you, there’s no banker scare going on in East Asia at the moment.

And the last of the three categories is business. Now, when I say business I don’t mean people who actually do business, I mean people who are either skilled workers who have money, or people who are in any way involved in actual work that requires some sort of skill or some sort of investment, and you really want to fall into that group. Why? Well, first off, you’re not really scary and there’s not many negative stories told about you, there’s no banker scare going on in East Asia at the moment.

Stereotypes

The other thing is that if you’re not negatively impacted by a stereotype, you’re very likely to be impacted positively by a lot of other stereotypes. So, basically, once you get the negative stereotypes out of the way, you get access to the huge pool of positive stereotypes, especially if you’re European or American, because every movie that’s out there – all of the movies, all of the cartoons, all of the sitcoms they import, they have these cool white people going around, so if you manage to fall in there, you’re good. People will be really friendly. You’re kind of falling into that category over there (see left-hand image above).

The other thing is that if you’re not negatively impacted by a stereotype, you’re very likely to be impacted positively by a lot of other stereotypes. So, basically, once you get the negative stereotypes out of the way, you get access to the huge pool of positive stereotypes, especially if you’re European or American, because every movie that’s out there – all of the movies, all of the cartoons, all of the sitcoms they import, they have these cool white people going around, so if you manage to fall in there, you’re good. People will be really friendly. You’re kind of falling into that category over there (see left-hand image above).

By the way, the suit trick also works in Hong Kong, you just look like another banker and no one cares what you do, because there are bankers everywhere. Now, how do we exploit that? It’s actually kind of straightforward, you do it like this (see image to the right). And even though you’re wearing a suit and you’re talking in loud English, and you’re abusing everything I’ve shown you so far – if all of that fails, then you use the so-called Dumb Foreigner Card. Here is how it works: I’m going to explain it to you by example. I took a trip down to Osaka a couple of years back with a buddy of mine, and we took the Shinkansen, which is a super express train and it’s really, really expensive, it’s like $200 one way, and we got one ticket for going there and another ticket for coming back. And I was sleepy, so I inadvertently invalidated my return ticket.

By the way, the suit trick also works in Hong Kong, you just look like another banker and no one cares what you do, because there are bankers everywhere. Now, how do we exploit that? It’s actually kind of straightforward, you do it like this (see image to the right). And even though you’re wearing a suit and you’re talking in loud English, and you’re abusing everything I’ve shown you so far – if all of that fails, then you use the so-called Dumb Foreigner Card. Here is how it works: I’m going to explain it to you by example. I took a trip down to Osaka a couple of years back with a buddy of mine, and we took the Shinkansen, which is a super express train and it’s really, really expensive, it’s like $200 one way, and we got one ticket for going there and another ticket for coming back. And I was sleepy, so I inadvertently invalidated my return ticket.

So, what happened? We figured that out when we tried to leave, so I got my buddy who is a native Japanese person walk up to the ticket counter and say: “Yeah, you see, my friend over here, he was sleepy, so he invalidated his ticket, and now he can’t use it anymore, and could you please give us a new one?” And their answer was: “Well, we could do that, but it’s going to take us about 24 hours to verify whether that’s true. We’re going to go to the gate and we’re going to see if his old ticket is in there,” and so on.

We didn’t have that time, so I just asked him to go to another one and try something else, so he walks up to a different ticket counter and he goes: “Well, you see, I have this friend, and my friend is kind of a foreign idiot, and being the foreign idiot that he is, he just lost his return ticket.” And their reply was: “Yeah, that’s not a problem, here is a new one.” We’re going to come back to this in a bit, because this is your last line of defense.

What we’re going to look at next is ‘home insecurity’. I have this basic approach that if anyone has access to your home, your work machine, your server, or your fridge – you’re screwed.

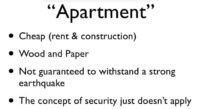

If you look at home security in Japan, you basically look at two different categories of homes: you have the apartment category over here (see left-hand part of the image), and you have the mansion category (right-hand part). Apartment and mansion don’t really mean what they mean to Western people or even other Asian people.

If you look at home security in Japan, you basically look at two different categories of homes: you have the apartment category over here (see left-hand part of the image), and you have the mansion category (right-hand part). Apartment and mansion don’t really mean what they mean to Western people or even other Asian people.

Apartment

An apartment is basically cheap in terms of rent and construction, apartments are mostly built out of wood and paper, and they’re not guaranteed to withstand a strong earthquake. To the contrary, you actually sign a clause that if an earthquake above magnitude 6 should strike, you acknowledge that this building will actually collapse.

An apartment is basically cheap in terms of rent and construction, apartments are mostly built out of wood and paper, and they’re not guaranteed to withstand a strong earthquake. To the contrary, you actually sign a clause that if an earthquake above magnitude 6 should strike, you acknowledge that this building will actually collapse.

So, they’re a cheap form of living, and if you want to know about security, there is no security. Your window is isolated with rubber, so you can just push a coat hanger through there and open it without damaging it, but it doesn’t really matter, because it’s just a window, and if you have a rock, you can just throw it in a second anyway. If you look around, there is some hope over here: this window is, obviously, closed off with a rail, which is very nice (see left-hand image).

So, they’re a cheap form of living, and if you want to know about security, there is no security. Your window is isolated with rubber, so you can just push a coat hanger through there and open it without damaging it, but it doesn’t really matter, because it’s just a window, and if you have a rock, you can just throw it in a second anyway. If you look around, there is some hope over here: this window is, obviously, closed off with a rail, which is very nice (see left-hand image).

It brings up the question: why did they take the least accessible and smallest window in the entire apartment to wire it up instead of the big one leading to the balcony? I figure it’s so that they won’t ruin my view on the other apartment that is 50 centimeters away. But there is a much bigger problem here. So, we’ve seen the wired window, and now let’s take a closer look. Can anyone spot a flaw in this security design? (see left-hand image) Yes, so let me introduce you to my new elite hacking tool – the screwdriver. And yes, you can take it off. You’ve got a door lock on that one, it’s fairly standard, you’ve got a pretty simple key. It takes about a minute to pick, not that I tried, because that would be illegal, ahem…

It brings up the question: why did they take the least accessible and smallest window in the entire apartment to wire it up instead of the big one leading to the balcony? I figure it’s so that they won’t ruin my view on the other apartment that is 50 centimeters away. But there is a much bigger problem here. So, we’ve seen the wired window, and now let’s take a closer look. Can anyone spot a flaw in this security design? (see left-hand image) Yes, so let me introduce you to my new elite hacking tool – the screwdriver. And yes, you can take it off. You’ve got a door lock on that one, it’s fairly standard, you’ve got a pretty simple key. It takes about a minute to pick, not that I tried, because that would be illegal, ahem…

One thing to give you some confidence is that your rental agreement will always have a clause which says: “Yeah, you know what? To prevent crime, we’ve actually tagged these keys, and no locksmith is allowed to make a copy.” So, if you look at it you go: “That’s actually kind of nice, because now only really hardcore criminals will have the technology to copy the keys.” Now, unfortunately, any of the stores I tried – none really cared. So, you just walk in and you go: “Hey, I would like a copy of this key,” and the guy at the counter will ask you: “Sir, are you aware that this key is copy protected?” And you say: “Yes, I am,” and he says: “OK.”

One thing to give you some confidence is that your rental agreement will always have a clause which says: “Yeah, you know what? To prevent crime, we’ve actually tagged these keys, and no locksmith is allowed to make a copy.” So, if you look at it you go: “That’s actually kind of nice, because now only really hardcore criminals will have the technology to copy the keys.” Now, unfortunately, any of the stores I tried – none really cared. So, you just walk in and you go: “Hey, I would like a copy of this key,” and the guy at the counter will ask you: “Sir, are you aware that this key is copy protected?” And you say: “Yes, I am,” and he says: “OK.”

Mansion

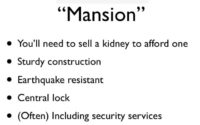

Now, let’s move on to the mansion type. The mansion type, part 1: you’ll need to sell at least one of your kidneys to afford it. They’re sturdily constructed, they’re earthquake resistant, they’re actually based on the model of a giant frying pan in the ground, on which the actual building stands. They are centrally locked and they often come with security services. Now, on the first view these are really nice from a security perspective, because, for example, here is the key (see left-hand image). It’s a bump key. It’s my current place, so I’m not going to show you the full bump.

Now, let’s move on to the mansion type. The mansion type, part 1: you’ll need to sell at least one of your kidneys to afford it. They’re sturdily constructed, they’re earthquake resistant, they’re actually based on the model of a giant frying pan in the ground, on which the actual building stands. They are centrally locked and they often come with security services. Now, on the first view these are really nice from a security perspective, because, for example, here is the key (see left-hand image). It’s a bump key. It’s my current place, so I’m not going to show you the full bump.

You have a security system installed; this actually links to a central company that surveils your apartment: a couple of sensors get activated, and they’ll come. You also have alarm buttons to call them directly. You have double locks, and the doors are actually metal enforced, so you can’t easily kick them in. And you have a central lock downstairs, so no one can come through that door either, and these locks actually use some sort of NFC, and I’ve tried to look into it today, but we couldn’t get a reading out of them. But either way, they’re touch enabled, so we’re finally safe.

You have a security system installed; this actually links to a central company that surveils your apartment: a couple of sensors get activated, and they’ll come. You also have alarm buttons to call them directly. You have double locks, and the doors are actually metal enforced, so you can’t easily kick them in. And you have a central lock downstairs, so no one can come through that door either, and these locks actually use some sort of NFC, and I’ve tried to look into it today, but we couldn’t get a reading out of them. But either way, they’re touch enabled, so we’re finally safe.

Well, not quite, because behind my apartment, I’m not sure if you can see this because the lights are kind of weird, there is this fence to protect the back entrance (image to the left). The fence has small height, and there is a pretty high stepping stone right next to it, so you’re not going to have to jump. You can basically quite comfortably walk over it. And then, once you’ve walked over it – oh, by the way, it has the same high security lock in there, so you can’t just open it, but if you walk over it, you take two steps and you get to the bicycle entrance which does not happen to be locked. So, yeah, we’re screwed again.

Well, not quite, because behind my apartment, I’m not sure if you can see this because the lights are kind of weird, there is this fence to protect the back entrance (image to the left). The fence has small height, and there is a pretty high stepping stone right next to it, so you’re not going to have to jump. You can basically quite comfortably walk over it. And then, once you’ve walked over it – oh, by the way, it has the same high security lock in there, so you can’t just open it, but if you walk over it, you take two steps and you get to the bicycle entrance which does not happen to be locked. So, yeah, we’re screwed again.

This is the home security system in itself (see right-hand image), and this one is interesting, because, like everything in Japan including the toilets, this thing can be programmed. Now, if you’re a dumb foreigner like me, this can be quite a challenge, and here’s what happened. I moved into this apartment, and I saw this and I thought: “Wow, this is really cool. I’ll have something to play with tomorrow. I’m not awake enough to do it today, but I’ll look at this thing tomorrow.”

This is the home security system in itself (see right-hand image), and this one is interesting, because, like everything in Japan including the toilets, this thing can be programmed. Now, if you’re a dumb foreigner like me, this can be quite a challenge, and here’s what happened. I moved into this apartment, and I saw this and I thought: “Wow, this is really cool. I’ll have something to play with tomorrow. I’m not awake enough to do it today, but I’ll look at this thing tomorrow.”

What I didn’t know is that the guy who lived in the apartment before me had programmed this thing, and the management company did not find it a required action to reset it to standard factory settings. So, the guy who lived here before me had this really, really brilliant idea. He had this idea that if it’s after 1 a.m., and your lights have been out for more than 20 minutes, and your doors are locked – you’re obviously either asleep or you’re gone. So, if anyone at that point should try to open the balcony door – that must obviously be an attacker or a kidnapper or whatever. So, the alarm system was set to basically dispatch the SWAT team to my apartment without verification if the door should be open after 1 a.m., and my lights have been out for more than 20 minutes.

No normal person would do this, unless of course you’re a 20-something white guy who just moved into Tokyo after a couple of years and decided: “Wow, it’s such a lovely night; I want to have a drink out there, overlooking the beautiful scenery.” I open the door, the alarm system goes off, and the metallic Japanese voice is going: “Intrusion prevention system activated, intrusion prevention system activated.” 20 seconds later, my cell phone rings, and there is some male voice going: “Yes, sir, someone is breaking into your apartment, we’ve just dispatched the SWAT team.” So, I tell him: “Dude, that was me. I missed it, I opened the door, it was me, you can trust me,” and he goes: “No, we can’t do this, because what if there is a kidnapper at your home and he’s holding a gun to your head and he’s forcing you to say that, so we have to come.”

And I appreciate that, because that’s obviously a right thing to do. That said, it’s 3 in the morning, I have to go to work the next day, and I don’t really feel like having a SWAT team searching my apartment for a hidden intruder. So, I bust out the dumb foreigner card; I stop trying to explain them what was going on, and I go: “Dude, let me talk to you directly here. I’m German, I just didn’t know.” After a five second pause, the guy on the other side of the telephone goes: “Oh well, I’ll call them back.” So, also, if you’re a kidnapper and you ever want to get rid of them, just pretend you’re German – apparently, it works.

Mailboxes in Japan

No matter if you live in an apartment or in a mansion, one of the other central parts you will run into is this thing: it’s a mailbox (see image). These are actually kind of cool: they’ve got number combination locks, rotation locks with 10 digits each. Now we’re going to look at how you can basically reduce the efficiency of a lock to zero in only four steps. If we look at the lock itself, we have an entropy of about 20^8. How do I come up with this number? Well, we have 20 numbers we can select: right turn, left turn, 10 digits, and an average person can obviously remember a phone number which is 8 digits, but this is a conservative guess – of course, if you want you can remember much longer combinations. Now, here is 20^8 – good luck cracking that lock; you probably have much better chance just breaking it open.

No matter if you live in an apartment or in a mansion, one of the other central parts you will run into is this thing: it’s a mailbox (see image). These are actually kind of cool: they’ve got number combination locks, rotation locks with 10 digits each. Now we’re going to look at how you can basically reduce the efficiency of a lock to zero in only four steps. If we look at the lock itself, we have an entropy of about 20^8. How do I come up with this number? Well, we have 20 numbers we can select: right turn, left turn, 10 digits, and an average person can obviously remember a phone number which is 8 digits, but this is a conservative guess – of course, if you want you can remember much longer combinations. Now, here is 20^8 – good luck cracking that lock; you probably have much better chance just breaking it open.

So, the country of Japan makes some really smart decisions to address this obvious problem of a secure lock: #1 – it’s legally prohibited for any rotation lock on a mailbox to have more than 3 digits. Alright, we still have an entropy of 20^3. #2 – legally force all locks to open in a clockwise-clockwise-counterclockwise pattern. #3, which kind of kills it, is legally force the first two digits of the combination to be the same. Now, those of you who are good with math may have figured that we are at this point down to 100 combinations.

The fourth part is actually not the government’s fault, it’s the fault of people who build these locks: there’s no crank that you have to activate, and no button to push, so if you just pull on the lock and try, at some point the mailbox is going to pop open if you apply the right amount of pressure. I ran some checks, and to do a full rotation it takes about 1.5 seconds to try a combination, so if you do a full rotation, you can rotate it to one digit. So, if we do a little math, we end up with a 50% unlock chance in 75 seconds and a 100% unlock chance in 150 seconds. But this is actually not the worst part.

There is a fairly large monthly apartment rental company in Tokyo which shall remain unnamed for this purpose that I’ve had the pleasure of living with twice several years apart. Now, I’m the weird kind of person who remembers codes for old credit cards and phone numbers that I used 10 years ago, so I still remembered the lock key for my mailbox. And I moved in there again earlier this year for a couple of months, and I found it very curious that my mailbox in a completely different area of town had the exact same code.

I figured there’re only 100 combinations, so the collisions are actually quite rational, so I asked the real estate agent lady, and she told me: “No, that’s not a coincidence; all of our mailboxes have the same code.” When I asked her if she happened to consider that it might be a bad idea, her answer was, and I quote: “Yeah, but who would try that?” Not me, that’s for sure.

PIN code locks in Korea

Let’s jump over to Korea for a second. So, we’ve seen the mail locks in Japan, we’ve got to take a look at common locks in Korea for a second, no necessarily mail. They look like this (see image), they are PIN code locks. They are installed onto your door, and of course, if you look at it, again, assuming that a person can remember a phone number, we get an entropy of 10^8, which is really high. The problem is that even though it’s not a law, most of these locks only take four digits.

Let’s jump over to Korea for a second. So, we’ve seen the mail locks in Japan, we’ve got to take a look at common locks in Korea for a second, no necessarily mail. They look like this (see image), they are PIN code locks. They are installed onto your door, and of course, if you look at it, again, assuming that a person can remember a phone number, we get an entropy of 10^8, which is really high. The problem is that even though it’s not a law, most of these locks only take four digits.

If you look at the manufacturers, most of them don’t go above that number, so we get an entropy of 10,000. And the real problem is that the vast majority of them are not wired to anything. There’s actually a small battery inside that you can replace from inside your apartment that powers the lock. And they also don’t really block you out after numerous attempts, or it’s a very short block out, because, of course, if the lock locks down for an hour, then a lot of kids in the neighborhood are going to have a really good time trolling you by just running around and punching random numbers into every door they find, and then when you come home your lock says: “Yeah, please try again in 48 hours.” So, obviously they can’t do that.

I ran some tests, and the average amount of time it takes to check out one combination is about 0.85 seconds over a span of 120. So, again, if we do some math, we got a 50% unlock chance in 66 minutes and a 100% unlock chance in a little over 2 hours. Now, if that was a mailbox I could say this is adequate, but this is your apartment, this is where you keep your passport, this is where you keep all of your important stuff, all of your tech, your money, if you store it at home. So, in that context, 2 hours to crack the lock without any sign is not a good idea.

Now, of course, the fact that the lock has a battery case on the other side kind of gives you an impression of how sturdy those doors are, so if you run out of time, just kick it in. But there is actually a way more interesting vector here to piss people off, if you’re into that, which you can see up here (see left-hand image). It says: “Emergency power DC9V.” So, obviously, if your battery is inside the apartment, and your battery runs out of power, you won’t be able to open your door even if you know the code, so there is this brilliant method that you can just take a 9 Volt battery you buy somewhere else, and you hold it up to these two pins up there, and then the lock will draw power from the battery.

Now, of course, the fact that the lock has a battery case on the other side kind of gives you an impression of how sturdy those doors are, so if you run out of time, just kick it in. But there is actually a way more interesting vector here to piss people off, if you’re into that, which you can see up here (see left-hand image). It says: “Emergency power DC9V.” So, obviously, if your battery is inside the apartment, and your battery runs out of power, you won’t be able to open your door even if you know the code, so there is this brilliant method that you can just take a 9 Volt battery you buy somewhere else, and you hold it up to these two pins up there, and then the lock will draw power from the battery.

![]() What that tells us, however, is that those two pins go directly into the circuitry of that lock. So, if you want to have a really good time and make a really bad time for a lot of people, you get yourself a couple of these locks, a high amperage car battery, and just blow them out.

What that tells us, however, is that those two pins go directly into the circuitry of that lock. So, if you want to have a really good time and make a really bad time for a lot of people, you get yourself a couple of these locks, a high amperage car battery, and just blow them out.

Now, how do you counter-exploit that? If you’re having an apartment in one of these two countries, you basically better assume that if someone wants to get into your apartment, they will. Now, this is true for all over the world: if you have enough resources and power, you can get into an apartment wherever you go, but it’s particularly easy here.

We’re going to move on to probably one of the most fun parts of this, at least if you like stories that make your hair stand up. We’re going to talk about corporate insecurity, which means, the reason why companies that you work for, or that you may consult for, or that you may test in either country, are not that up to speed and have all these weird security flaws, we’re not quite sure how this could have happened. And any security flaw you’ll find – and this is also applicable to Korea, but this is mostly for Japan – you have to look at 2 filters, 2 conceptual filters.

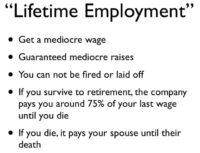

Number 1 is lifetime employment. What on earth is lifetime employment? Well, it basically means the company hires you fresh out of university and they guarantee you a mediocre wage – it’s not bad, it’s not really good, it’s mediocre wage. They guarantee you mediocre raises of anywhere between 3%-5% a year. And you cannot be fired or laid off; the company is not legally allowed to. You couldn’t make this contract in Europe, for example, but you can do it in Japan.

Number 1 is lifetime employment. What on earth is lifetime employment? Well, it basically means the company hires you fresh out of university and they guarantee you a mediocre wage – it’s not bad, it’s not really good, it’s mediocre wage. They guarantee you mediocre raises of anywhere between 3%-5% a year. And you cannot be fired or laid off; the company is not legally allowed to. You couldn’t make this contract in Europe, for example, but you can do it in Japan.

If you survive until your retirement, until you die they’ll pay you 75% of your last wage, and if you die your spouse is going to get the same amount of money until they die. While it may not be an appealing model to the hacker community where we do everything ourselves and we want to live our lives, for people who just want to run a family this is an incredibly appealing modeling. People who run pentests often forget this motivation base behind them.

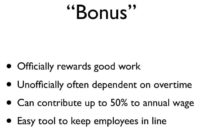

The other concept to look at is bonuses. Now, in most countries there is some form of bonus, but it’s usually either a couple of hundred dollars or a month wage. What we have in Japan is that it’s up to 50% of your annual wage, and when I say 50% I mean your bonus may be 12 months of your wage. So, if you get your bonus, you double. If you don’t get your bonus, you may not be able to pay your bills. Officially this is made to reward good work, unofficially it usually depends on who does the most overtime, and, really, it’s a tool to keep employees in line, because if you want to change something, you’re always running the risk of not getting your bonus, because even though they usually pay this to people every year, it’s not guaranteed in your contract.

The other concept to look at is bonuses. Now, in most countries there is some form of bonus, but it’s usually either a couple of hundred dollars or a month wage. What we have in Japan is that it’s up to 50% of your annual wage, and when I say 50% I mean your bonus may be 12 months of your wage. So, if you get your bonus, you double. If you don’t get your bonus, you may not be able to pay your bills. Officially this is made to reward good work, unofficially it usually depends on who does the most overtime, and, really, it’s a tool to keep employees in line, because if you want to change something, you’re always running the risk of not getting your bonus, because even though they usually pay this to people every year, it’s not guaranteed in your contract.

So, the entire thought process of an average worker, it doesn’t matter if it’s an engineer or middle management, or even upper management, in a Japanese company boils down to: “Don’t f**k up.” And when I say: “Don’t f**k up,” -“f**k up” is a “do” word; it requires action. As long as you remain passive, you cannot be blamed.

This sounds weird from an outsider’s perspective, so let’s look at an example. You’re working on a project, and you make a judgment call, because you see the situation is totally clear, and there’s a protocol in place, but the protocol is not particularly well defined, it was defined 20 years ago and you figure: “Wow, if we just did it this way, we could save this company millions.”

But something goes wrong, something you didn’t predict, maybe the country you tried to do business with had a military putch, something like that, and your company incurs a small loss. And when I say small loss, this could be $10, it’s enough. You screwed up – your bonus is gone. You’re not going to get it; you may get fired for it, because you obviously had that audacity to act against the company.

Now, on the other hand, if you pedantically stick to protocol, even if it’s completely wrong and it’s obvious that it’s wrong, and the company loses millions over this because you refuse to budge, because this is how you do it – as long as the company doesn’t go bankrupt over it, and this is kind of hard to do in Japan because most of the companies are subsidized by the government, your promotion will be secured. It doesn’t matter how badly you screw up from a human perspective, as long as you don’t do anything to screw up, you will get promoted and you will get your bonus and you will get all your stuff handed out to you. So, in a nutshell, don’t work too fast, stay until 1 a.m. and secure that bonus, or you can become a contractor, but then you’re kind of an outcast.

So, let me give you an example of how this actually plays out. In this example I’m going to run you guys through a fictional penetration test of a fictional company, not that this has ever happened to me in person, I just want to get your feedback and how you would react.

So, you go in, you fire up nmap, you run it against the customer’s network, and you find a Windows NT4 box that runs IRC on port 31337. Now, here’s the million dollar question: how would you react? I know this may be presumptuous, but I would assume the freaking box is owned; call it intuition.

So, I told the client that I never worked for the same thing, and their response was: “Ok, we’ll check into it. That seems like a very serious issue, we acknowledge that IRC should not be running on a Windows NT4 box in our corporate network.” This was on the Internet, by the way, and dialing out to other IRC servers to get commands.

“We’ll check into it,” and two weeks pass, and nothing really happens, so I decide to kind of poke them about it and go: “You know, that IRC box, the Windows NT4 box with IRC running, whatever happened to that one?” Here’s the reply with emotion added to express my feelings at the point that I heard it: “We have decided against shutting down or altering the affected machine, because the guy who set it up no longer works here and we have no idea what it does. But it might be important, so we’ll just leave it running.”

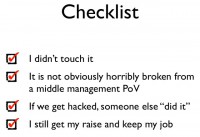

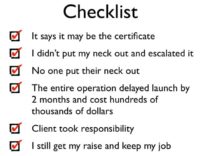

Now, can any of you spot a flaw in this approach? I mean, it’s flawed when you look from the outside, but from a checklist of an engineer it goes like: “I didn’t touch it. It’s not obviously horribly broken from a middle management PoV” (not obviously horribly broken, from a middle management PoV, means it’s not on fire), and when I say: “It’s not on fire,” I mean it’s not physically burning. A few more items from a checklist of an engineer are: “If we get hacked, someone else did it,” and “I still get my raise and keep my job.”

Now, can any of you spot a flaw in this approach? I mean, it’s flawed when you look from the outside, but from a checklist of an engineer it goes like: “I didn’t touch it. It’s not obviously horribly broken from a middle management PoV” (not obviously horribly broken, from a middle management PoV, means it’s not on fire), and when I say: “It’s not on fire,” I mean it’s not physically burning. A few more items from a checklist of an engineer are: “If we get hacked, someone else did it,” and “I still get my raise and keep my job.”

So, how do we exploit that if we run pentests in Japan? Number 1: you can assume that stuff won’t be fixed. If you find it weird to find NT4 servers running secure services, then you’ve obviously not done many pentests in Eastern Asia, because it’s extremely common. Because what usually happens is someone sets them up and they work somewhere else, so no one knows what the box does and no one wants to touch it, because something bad may happen, and then you did the bad thing, and then you’re fired.

Number 2 is: if you can create a responsibility setting, then no one will disturb you. A responsibility setting is something like this: you’re running a pentest, someone walks up to you and goes: “What are you doing?” and you go: “Well, I’m here on behalf of…” (find the name of some middle manager or upper manager – anyone who outranks anyone in the building at the moment that cannot be reached because they’re on vacation). “Will you be responsible when he finds out that you disturbed me?” I’ve never been talked to after that sentence.

Number 2 is: if you can create a responsibility setting, then no one will disturb you. A responsibility setting is something like this: you’re running a pentest, someone walks up to you and goes: “What are you doing?” and you go: “Well, I’m here on behalf of…” (find the name of some middle manager or upper manager – anyone who outranks anyone in the building at the moment that cannot be reached because they’re on vacation). “Will you be responsible when he finds out that you disturbed me?” I’ve never been talked to after that sentence.

Let’s jump to wireless for a second. So, if any of you have been wardriving recently in a European city or in an American city, and you’ve seen all of those lovely WPA2-secured hotspots, and you remember the good old days where you would find open hotspots everywhere belonging to private people who couldn’t configure their router – well, the good old days are well and alive in Tokyo. This is a recent screenshot (see right-hand image).

Let’s jump to wireless for a second. So, if any of you have been wardriving recently in a European city or in an American city, and you’ve seen all of those lovely WPA2-secured hotspots, and you remember the good old days where you would find open hotspots everywhere belonging to private people who couldn’t configure their router – well, the good old days are well and alive in Tokyo. This is a recent screenshot (see right-hand image).

So, at a random place we see that two of them are open, three of them are using WEP, two of them are using WPA, and only one of them is using WPA2. This is not really the worst part yet. The worst part, if you really look at it, is these guys (left-hand image above). These are the three major Japanese mobile carriers: SoftBank, au by KDDI, and NTT DoCoMo.

So, at a random place we see that two of them are open, three of them are using WEP, two of them are using WPA, and only one of them is using WPA2. This is not really the worst part yet. The worst part, if you really look at it, is these guys (left-hand image above). These are the three major Japanese mobile carriers: SoftBank, au by KDDI, and NTT DoCoMo.

And these guys have serious issues with their traffic, because mobile traffic has just completely exploded over the last couple of years. So, what they did is they came up with a fairly interesting system, where they just set up Wi-Fi hotspots, standard 802.11 Wi-Fi hotspots, and if your cell phone runs with one of these companies it will automatically detect the hotspot if it’s nearby and automatically sign you in.

So, if you use a SoftBank phone and you sit in a cafe that has a SoftBank hotspot, and that’s about all of them, your phone will automatically log in and it will shoot all of your data over that particular hotspot, saving the company lots of data traffic.

Now, these will not actually allow you to connect with a computer – well, they will allow you to connect, but they won’t allow you to get through the router. They do that by filtering a) MAC address and b) the user-agent that your machine sends when it connects to the router for the very first time. As you can plainly see, this is absolutely secure and no one could ever really break into that, and since SoftBank tried to sue the hell out of the last guy who revealed how exactly you break into them – I’m not going to tell you, but if you have a sniffer set up it’s going to take you about 20 seconds.

But even when you look at this in Japan, Korea really takes the cake here, because this is a screenshot from last year in Korea (see right-hand image). Can anyone spot a problem? So, if you go to Korea and you like using Skype, you don’t really have to buy a data plan or a foreign SIM or roaming or anything, you just log into one of the hotspots; the whole Seoul is covered by open hotspots belonging to some person.

But even when you look at this in Japan, Korea really takes the cake here, because this is a screenshot from last year in Korea (see right-hand image). Can anyone spot a problem? So, if you go to Korea and you like using Skype, you don’t really have to buy a data plan or a foreign SIM or roaming or anything, you just log into one of the hotspots; the whole Seoul is covered by open hotspots belonging to some person.

Now, exploitation vector: I don’t really know what we could possibly do with anonymous public open Internet access; I’ll let you guys figure that one out. While we’re talking about Korea, I would like to ask a question, and I’m taking all guesses here: what’s the browser market share for Internet Explorer, all versions of it, in South Korea at this very moment? 83? 90? It’s actually 97%.

Let me spell that out for you: it’s Ninety-Seven Percent. Here’s a graph: unfortunately, it stops at 2010, I couldn’t find a newer one (image to the left). The thing that really creeped me out personally is if you look up here, the dark blue line is IE6 – it’s going up!

Let me spell that out for you: it’s Ninety-Seven Percent. Here’s a graph: unfortunately, it stops at 2010, I couldn’t find a newer one (image to the left). The thing that really creeped me out personally is if you look up here, the dark blue line is IE6 – it’s going up!

What on earth is going on in South Korea with browsers? Any ideas? This is really funny because it’s one of those things that’s really big about Korea, but no one else ever looks into it. SSL or TLS or whatever you want to look at – it’s universal, right? We use it in every country. Yeah, let me show you this map of the adaption of SSL standard. Do you see the red spot? (see right-hand image) By the way, green means they use SSL. So, the red spot is called South Korea.

What on earth is going on in South Korea with browsers? Any ideas? This is really funny because it’s one of those things that’s really big about Korea, but no one else ever looks into it. SSL or TLS or whatever you want to look at – it’s universal, right? We use it in every country. Yeah, let me show you this map of the adaption of SSL standard. Do you see the red spot? (see right-hand image) By the way, green means they use SSL. So, the red spot is called South Korea.

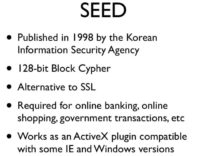

Let me introduce SEED. SEED is an encryption algorithm developed in 1998 by the Korean Information Security Agency, it’s a 128-bit block cypher, and it wasn’t developed as an alternative to SSL, it actually predates SSL’s public availability in many regions. So, what they did is they basically spun off this entire new algorithm, and until this day it’s required for online banking, online shopping, government transactions, paying your taxes – basically, in any secure online communication you want to do with a Korean company, you have to use SEED.

Let me introduce SEED. SEED is an encryption algorithm developed in 1998 by the Korean Information Security Agency, it’s a 128-bit block cypher, and it wasn’t developed as an alternative to SSL, it actually predates SSL’s public availability in many regions. So, what they did is they basically spun off this entire new algorithm, and until this day it’s required for online banking, online shopping, government transactions, paying your taxes – basically, in any secure online communication you want to do with a Korean company, you have to use SEED.

Now, SEED runs as an ActiveX plug-in, so unless you’re using some version of Windows and some version of Internet Explorer, you cannot use SEED, and your computer basically gets degraded to a toy to look at cats, because you cannot build an encrypted channel.

Mozilla tried really hard to implement SEED; they did it. There are still some companies that the government refuses to sign with their own keys. So, if you’re in Korea you will use Internet Explorer, and this also explains why IE6 is going up: because people were upgrading to Windows Vista or Windows 7 at some later points, and they had lots of complications, because, of course, as an ActiveX component, it’s fairly sensitive to the OS you’re running, so people just switched back to XP, and since they already switched back, they figured: “Yeah, better not upgrade that browser because it may break it again.”

Here are some of the effects that SEED is having. Number 1 is that there is really slow adaption to new Windows versions, as we’ve already seen. Alternative browsers and OS’s are basically useless and are perceived as toys, because you can’t really do anything that’s really working with them. It’s integrated with most cell phones; that’s one of the cool things: your cell phone has a unique ID, and if you tell that to your bank, your cell phone is able to actually log into your bank account, and it will do a two-factor authentication.

The two-factor authentication is actually the kicker, because many of the communications that SEED does are two-factor, so the certificates on the user end are given out by the government. So, if you access a SEED-protected site, you become 100% traceable. Since you’re 100% traceable, people don’t really see the need to secure web applications, because if you’re going to hack it, they’re going to know who you are anyway.

We’re going to talk about this in a bit again. In a nutshell, if you’re talking about Korean security, or if you’re planning to do a pentest over there, look into the RFCs for SEED, they’re very complex. It’s not a bad algorithm at all, it’s just an algorithm that no one ever uses anywhere outside of Korea, which completely replaces SSL within a country. This also means that if you’re working with a Korean developer and they’re writing something for you, don’t expect them to know how SSL works, because it’s simply not relevant to their lives.

In this particular case, how do you exploit it? Well, FUD.

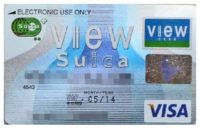

Next thing we’re going to look at is what I like to call the Too-Near Field Communication, which is kind of an international topic, because if you look at these couple of near-field communication cards (see right-hand image), the majority of those that are shown here are based on Sony FeliCa model.

Next thing we’re going to look at is what I like to call the Too-Near Field Communication, which is kind of an international topic, because if you look at these couple of near-field communication cards (see right-hand image), the majority of those that are shown here are based on Sony FeliCa model.

The Japanese have taken this concept of near field communication, and they’ve taken it to another completely different level. I would like to introduce you to what I think is the worst idea in human history: it’s the NFC-enabled Visa card (see left-hand image).

The Japanese have taken this concept of near field communication, and they’ve taken it to another completely different level. I would like to introduce you to what I think is the worst idea in human history: it’s the NFC-enabled Visa card (see left-hand image).

Now, this does not actually allow you to charge your Visa, but your card has a preset limit that you can set to whatever you want; you can set it to $200, and whenever your card empties, it will automatically charge another $200 to your card and will recharge the payment card that’s on it. In this case it’s Suica card that’s intergraded.

If you try to convince anyone anywhere else in the world to use a credit card that is NFC-enabled that bills directly to your credit card, people will look at you and go: “Are you f**king nuts?” The reason why this works in Japan is because the same technology has already been around for years and it’s been integrated in cell phones, so these cell phones (see image to the right) have NFC technology in them, something that we’re just slowly seeing in other countries, and you can pay with them, and whatever you pay with them gets charged to your phone bill.

If you try to convince anyone anywhere else in the world to use a credit card that is NFC-enabled that bills directly to your credit card, people will look at you and go: “Are you f**king nuts?” The reason why this works in Japan is because the same technology has already been around for years and it’s been integrated in cell phones, so these cell phones (see image to the right) have NFC technology in them, something that we’re just slowly seeing in other countries, and you can pay with them, and whatever you pay with them gets charged to your phone bill.

So, people are already really used to the concept of “Yeah, I have this unlimited bill that I can use with NFC, it’s really practical, because all I have to do is *BEEP*”

So, why is this a problem? First, it’s used virtually anywhere if you’re in Japan. There’s a couple of stores where you can’t even pay in cash, they only take NFC; a popular example are the trains. If you want to get on a train, you have to buy a ticket. In many stations only 2 out of 10 ticket gates will have real ticket slots; everything else only takes NFC, so you’re basically bound to carrying a Suica or FeliCa card with you.

You have this automatic recharging, and it’s actually accepted by a lot on online stores by now. And you need to get a reader like this one, it’s called FeliCa reader (see left-hand image), you can buy them on Amazon for about $10. They come with drivers, really easy to install. And the weird thing about the cards is that on the chip they will store your last 20-something transactions. This may be anything: this may be something you buy, or this may be a train you get on, or it may be the train you get off.

You have this automatic recharging, and it’s actually accepted by a lot on online stores by now. And you need to get a reader like this one, it’s called FeliCa reader (see left-hand image), you can buy them on Amazon for about $10. They come with drivers, really easy to install. And the weird thing about the cards is that on the chip they will store your last 20-something transactions. This may be anything: this may be something you buy, or this may be a train you get on, or it may be the train you get off.

So, if you have this reader and you plug it into your PC, and you get anyone’s card in the near proximity of it, you can extract a view like this (right-hand image). And this is actually not a hacker tool; this tool comes with the reader.

So, if you have this reader and you plug it into your PC, and you get anyone’s card in the near proximity of it, you can extract a view like this (right-hand image). And this is actually not a hacker tool; this tool comes with the reader.

So, by now, what do we have? We get someone’s NFC data – their card, or their cell phone; we got location tracking and we got purchase tracking, which obviously leads to some problems down the road somewhere. But what really makes it bad is that if you look at Amazon.co.jp, you can see that you can actually pay with your Osaifu-Keitai card (image to the left), and all you need is the exact same reader, so you plug in your reader, you go to Amazon, you say: “Yeah, I want to buy this,” and they go: “Ok, what do you want to pay with?” “I want to pay with NFC” – “Cool”. Touch your card to the receiver attached to your computer, beep – and you’ve paid.

So, by now, what do we have? We get someone’s NFC data – their card, or their cell phone; we got location tracking and we got purchase tracking, which obviously leads to some problems down the road somewhere. But what really makes it bad is that if you look at Amazon.co.jp, you can see that you can actually pay with your Osaifu-Keitai card (image to the left), and all you need is the exact same reader, so you plug in your reader, you go to Amazon, you say: “Yeah, I want to buy this,” and they go: “Ok, what do you want to pay with?” “I want to pay with NFC” – “Cool”. Touch your card to the receiver attached to your computer, beep – and you’ve paid.

Obviously, what we can do with it is we can buy stuff on other people’s tabs. You open up Amazon on your laptop, you have some sort of cellular connection, you go to Pay, you take your reader, you walk up to some guy and do “BEEP”, because there’s no authentication, and you’ve just paid for it.

Now, I’ve taken a lot of crap for this particular point, because people always bring up the same defense, they say: “But Paul, the FeliCa standard particularly specifies that to prevent this we’re only going to allow this across millimeters with private readers.” So, they can do centimeters with commercial readers, but as an individual you can only get readers to allow you to read these cards from about 2 or 3 millimeters away, and you couldn’t possibly get that close to another person without him noticing. That’s just ridiculous.

Anyone who believes this has obviously never taken the morning commute train in Tokyo, because this is what it looks like, and this is not staged (see right-hand image). This is fairly common. This is a Tokyo line train, it’s a rapid commuter express. It only comes every 20 minutes, so if you miss it you’ll be late for work, and this is how they make sure that everyone gets on the train. Obviously, the inside pressure is still too high, so they need to get more people to be able to push in. So, anyone who wants to tell me that in this setting I couldn’t possibly get within 3 millimeters of this guy’s purse or wallet is trying to kid me. If you want to really shoot it off, have an emergency flight the next morning and carry two suitcases and try to get in there.

Anyone who believes this has obviously never taken the morning commute train in Tokyo, because this is what it looks like, and this is not staged (see right-hand image). This is fairly common. This is a Tokyo line train, it’s a rapid commuter express. It only comes every 20 minutes, so if you miss it you’ll be late for work, and this is how they make sure that everyone gets on the train. Obviously, the inside pressure is still too high, so they need to get more people to be able to push in. So, anyone who wants to tell me that in this setting I couldn’t possibly get within 3 millimeters of this guy’s purse or wallet is trying to kid me. If you want to really shoot it off, have an emergency flight the next morning and carry two suitcases and try to get in there.

Alright, I think we’ve confirmed that with this technology and a little bit of evil spirit we can do location tracking, we can do purchase tracking, and we can buy stuff on other people’s tabs by simply abusing the rush hour in the morning.

After I’ve shown you all of this cool stuff that we can do and all these weird vectors, we’re going to sum them up a little, and we’re going to look at what I like to call the Top 3 Hit List, which is basically the top 3 things I’ve seen in the last 6-7 years, that made me go: “Huh?” and that I’m allowed to disclose, because they’re not under NDA anymore, or because they never were to begin with.

Airport Security

Number 3 is the most harmless and it’s called Airport Security. Now, if you go to Narita airport and you check in, you have to put your passport on a certain reader which reads the chip inside, if it’s already a chip-enabled passport, and will check whether your passport is correctly signed, all of this stuff. So, this is the machine, it’s very nice (see image). It also checks you in if it finds you. This thing handles all of your passport data, so what I find slightly unnerving was watching it boot, because this screen came up (on the image). What I found more unnerving is that the very day I took that picture was the day where a remote 0day was published for XP SP2, so we know that the box was hackable at that particular point.

Number 3 is the most harmless and it’s called Airport Security. Now, if you go to Narita airport and you check in, you have to put your passport on a certain reader which reads the chip inside, if it’s already a chip-enabled passport, and will check whether your passport is correctly signed, all of this stuff. So, this is the machine, it’s very nice (see image). It also checks you in if it finds you. This thing handles all of your passport data, so what I find slightly unnerving was watching it boot, because this screen came up (on the image). What I found more unnerving is that the very day I took that picture was the day where a remote 0day was published for XP SP2, so we know that the box was hackable at that particular point.

“Ultra Secure” JavaScript

Number 2 is what I like to call the “Ultra Secure” JavaScript, which is a technology often employed in Japan; I’ve seen this a couple of times, this is just one example (see right-hand image). This is a router; you need to log in to use it. It’s a standard router, it was actually used as a pay router in a cafe, so they said: “If you want to use the Internet, please enter your credit card details here.” So, I just figured out: “Well, I’m kind of bored, let’s look at the source for this.”

Number 2 is what I like to call the “Ultra Secure” JavaScript, which is a technology often employed in Japan; I’ve seen this a couple of times, this is just one example (see right-hand image). This is a router; you need to log in to use it. It’s a standard router, it was actually used as a pay router in a cafe, so they said: “If you want to use the Internet, please enter your credit card details here.” So, I just figured out: “Well, I’m kind of bored, let’s look at the source for this.”

Here is the source; can anyone spot a flaw? (see left-hand image) Let me give you a hint: it’s this part of JavaScript that says “var password”. It gets worse: if password equals this, then call the function “send_login”. So, the entire authentication was done in JavaScript, and this is a run-of-the-mill standard router produced by a huge Japanese manufacturer of routers. This is not a fluke; there were tens of thousands of these things deployed, and we all know how often router firmware gets updated.

Here is the source; can anyone spot a flaw? (see left-hand image) Let me give you a hint: it’s this part of JavaScript that says “var password”. It gets worse: if password equals this, then call the function “send_login”. So, the entire authentication was done in JavaScript, and this is a run-of-the-mill standard router produced by a huge Japanese manufacturer of routers. This is not a fluke; there were tens of thousands of these things deployed, and we all know how often router firmware gets updated.

Security Flaws: Non-Critical?

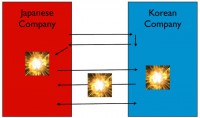

But this is nothing compared to the grand finale. The grand finale happened while I was working for a Japanese company, consulting for them in the mix of development and security efforts, and they asked a Korean company to provide them with software, so the Korean company would develop it.

So, they gave them the contract, and the Koreans looked at it and they go: “Ok, we know how this works.” So, they developed it and they sent it back to us. Now, the client remembers that I have a security background and goes: “Yeah, you know what, can you test this? We know you’re busy, but just take 20 minutes out of it, just give it a rough look.”

So, what I do is I go to the login form, I hit Shift and I hit the numbers 01 and I hit Enter, and the server comes back with: “SQL query Upper Quote cannot be found because of malformed query,” and I go: “Ok, there may be something wrong here.”

It turns out the thing is an absolute catastrophe, and when I say absolute catastrophe, the damn vulnerable web app prototype kit that you practice your web attacks against would be considered secure against what these guys delivered.

So, we had everything: we had RFI, LFI, XSS, we had SQL injection on the main page, SQL queries weren’t filtered at all. But my personal favorite was the fact that it stored credit card numbers in plain text in database, and you could look at that from the admin interface, and the admin interface was secured with JavaScript, and by that I mean there was JavaScript that would check a cookie on your machine, and if the cookie was not set – by the way, the cookie had to be set to 1 – it will call the JavaScript Back function to send you back to the previous page.

So, obviously, if you just disabled freaking JavaScript, you could look at the admin panel and use it the way you want, because there was no other authentication going on. All the login form for the admin interface did was set this cookie to 1. Obviously, we have some really big security issues with this thing.

So, the Japanese got this, I’m not going to reveal to you how I got them to accept that there might be security issues, but they sent it back to the Koreans, the Koreans looked at it and they figured out that there were some issues, and, of course, it explodes with them, and one developer gets fired because he should have known, he was supposed to be the foreign technology guy. Another issue was that they got SSL warning, because the certificate they were using simply did not match the domain name. They’ve got a signed certificate, but it was not for the correct domain name, so of course we got a huge warning for that.

But what happened after this is that the communication between the Korean company and the Japanese company exploded as well, because the Koreans accused the Japanese of being rude, and the Japanese accused the Koreans of being lazy. So, we’re back at where we are right now, basically.

But what happened after this is that the communication between the Korean company and the Japanese company exploded as well, because the Koreans accused the Japanese of being rude, and the Japanese accused the Koreans of being lazy. So, we’re back at where we are right now, basically.

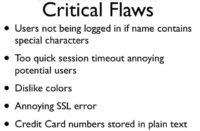

To quiet it down we got another consultant who was fluent in Korean, and we set up this huge meeting, and during the meeting, basically, they worked together to identify 2 sets of flaws: they identified the critical flaws which had to be fixed before launching, and they identified the non-critical flaws which had to be fixed whenever, at some point while we’re making money.