Nick Farr, a well-known inspirer of the Hackerspaces idea in the United States and the author of the Hackers on a Plane project, delivers a great talk ‘Yes We Could: Hackers in Government’ at the SIGINT event held by the Germany-based Chaos Computer Club to express his viewpoints on how governments would function if they were run by hackers instead of politicians.

This talk is about hackers in governments. Just to give you a little bio: I am an accountant based in Washington, DC. I worked for a lot of different clients both within government and people who were trying to influence, lobby or are working for government in different ways.

This talk is about hackers in governments. Just to give you a little bio: I am an accountant based in Washington, DC. I worked for a lot of different clients both within government and people who were trying to influence, lobby or are working for government in different ways.

When I first got to Washington, DC, I started working for the Treasury Department, for the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund, which helps provide funding and channels, resources from the private sector into credit unions and smaller agencies that provide credit and financial services to entities that don’t traditionally have access to commercial credit and are trying to empower smaller units, Native American units into providing financial services that are not classically provided by the private sector.

I’ve have also worked for the consulting firm McKinsey & Company; a community action agency in Washington, DC called The United Planning Organization, which provides a lot of social services and resources to low-income people in Washington, DC. And I have to add: yes, I helped Makerbot prepare their taxes for the last year.

You might also know me, I ran this little project in 2007 called Hackers on a Plane, and I have another Hackers on a Plane, there are 5 Americans here at SIGINT. We’re enjoying this conference; next we’ll be going to Poland for CONFidence, and then we’ll see you next weekend in Berlin for PH-Neutral.

A lot of people also know me because I’ve been active in promoting Hackerspaces, an idea which I fell in love with here in Germany, and thought that if we could just import this concept into United States it would take off and do really, really excellent things for the hacker community in the US, and over the past 3 years that’s definitely proven to be the case.

The expansion in Hackerspaces based on the model that was pioneered here in Germany has been explosive, and it’s grown in ways that I couldn’t even imagine. There’s so many Hackerspaces being built all over the United States that I keep hearing about, and I think it’s a great, wonderful thing. And I have to thank the hacker community here in Germany for pioneering that concept and testing it and going through a lot of the difficult lessons so that hackers in the United States didn’t have to. Actually, give yourselves a round of applause for Hackerspaces in Germany and pioneering that. I’m very grateful for that.

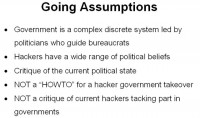

But this talk is not about hackers that are presently in governments. The first slide that I had here was Mudge testifying before Congress (see left-hand image). It’s not saying that I think hackers should automatically go and take over the government, things like that. The theoretical construct that I’m coming from in this talk is if one day instead of politicians in leadership we had hackers, and what a fundamental and radical shift that would be in government.

But this talk is not about hackers that are presently in governments. The first slide that I had here was Mudge testifying before Congress (see left-hand image). It’s not saying that I think hackers should automatically go and take over the government, things like that. The theoretical construct that I’m coming from in this talk is if one day instead of politicians in leadership we had hackers, and what a fundamental and radical shift that would be in government.

I’m going to address this in a later slide, but I think that when it comes to looking at the reality of large, complex technical systems, hackers and politicians are approaching from two diametrically opposite viewpoints.

And so, just to introduce a couple of the assumptions that I’m working with right here, the first of which is: instead of viewing government as this big, sort of nebulous thing that’s run by politicians and bureaucrats, try to think of governments as a complex discreet system, which, indeed, is led by politicians and run by bureaucrats, just like the Internet and network structures, the way code is written, the way that code is executed within a machine is a complex discreet system. I think that you can look at governments the same way that you would look at a network infrastructure or at the way a computer runs.

And so, just to introduce a couple of the assumptions that I’m working with right here, the first of which is: instead of viewing government as this big, sort of nebulous thing that’s run by politicians and bureaucrats, try to think of governments as a complex discreet system, which, indeed, is led by politicians and run by bureaucrats, just like the Internet and network structures, the way code is written, the way that code is executed within a machine is a complex discreet system. I think that you can look at governments the same way that you would look at a network infrastructure or at the way a computer runs.

Another thing that I think is important to mention is that the common misconception of hackers, I think, all around the world, is that they have a hive political mind. I don’t believe that is the case, especially in the United States where you have hackers that have very traditional right wing beliefs and hackers that have traditionally left wing beliefs. I think there is a lot of agreement, especially in the areas of Internet policy, and the way that we deal with technical systems and copyright law, I believe there’s a lot of agreements and a lot of the work that the Pirate Party is doing in their platform here in Germany and throughout the world, and similar efforts run by hackers in the United States are very common.

But when it comes to things like tax policy, when it comes to things like budgets, and when it comes to how we handle social services, I think there is a wide range of beliefs within the hacker community on those sorts of things. And my talk is not necessarily aimed at saying that hackers should, or will, or are going to do any one or two things. What I’m looking at is how hackers would approach the problem.

Everybody has their own set of political theories and beliefs, and hackers are no different from anybody else in that respect, but I still believe that hackers, regardless of their political affiliation, would look at and address and see the core truth of the problem, and apply policies honestly, and describe their beliefs honestly in ways that politicians might not.

The other thing is I’m not looking here to say whether hackers that are currently in government are doing something correct; I’m not looking to profile what hackers that are in government are doing. This is more of a theoretical sort of thought piece. And along those lines I’m going to try to allow a lot of time for questions and answers and try to encourage a sort of discussion within the group over things that are happening and things that could happen, and how hackers could fundamentally influence government.

But again, I want to make a very strong disclaimer that I’m not attempting to advocate a political belief or a political theory one way or another. I’m just trying to say that if hackers replaced politicians, suddenly, one day, how government might function fundamentally differently, and how, regardless of political belief, I think that it would be far more democratic.

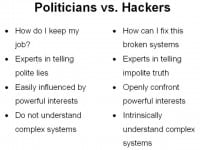

To sort of illustrate the general idea of politics, I think politicians’ driving core assumption is: “How do I keep my job? How do I line up the people who vote for me, tell them one thing to make sure that they’ll continue to vote for me? And how do I tell the people who provide me money, the people who are my political patrons, how do I tell them another thing that will help them give me the patronage and support that I need to keep my job?”

To sort of illustrate the general idea of politics, I think politicians’ driving core assumption is: “How do I keep my job? How do I line up the people who vote for me, tell them one thing to make sure that they’ll continue to vote for me? And how do I tell the people who provide me money, the people who are my political patrons, how do I tell them another thing that will help them give me the patronage and support that I need to keep my job?”

This is very common; it’s not a radical thing to say that politicians are fundamentally more interested in keeping their job than anything else. The difference with that, and I see this with hackers that are working in the bureaucracy: their core driving interest is not keeping their job, but fixing this broken system.

And sort of moving on from that, politicians are really experts at twisting words and twisting the truth and creating nice-sounding things that talk completely around the problem, whereas hackers are unafraid to tell management, unafraid to tell their customers, unafraid to tell anybody exactly what they think in absolutely no uncertain terms. And that, I think, is one really big fundamental difference, that if you replaced politicians with hackers, and hackers had a view and outline of what’s going on, they wouldn’t be afraid to say exactly how it is in very impolite terms.

Just to take a quick step back: how many people in the audience right now would describe themselves as a hacker, if I were to ask you: “Are you a hacker: yes or no?” How many people would say they are a hacker? Ok, on that note, how many people in this room have told somebody about them in a workplace situation or in a political situation what the truth exactly was, in, perhaps, a manner that was not so polite?

The shocking thing is that I had more hands raised in answer to that question than the hacker question. But that’s exactly what I’m getting at: politicians don’t do that. They don’t have the courage to do that, and I think hackers fundamentally have the courage to say in no uncertain terms what the problem is, how to fix it, regardless of whether or not that’s politically expedient. And most of the time it’s not politically expedient, otherwise politicians would tell the truth.

The other thing is, politicians are easily influenced by powerful interests. Really, when you look at political systems in modern Western democracies, the politicians are sort of stuck in the middle between the people that vote for them and the people that support them. And I think it’s very rare to find politicians who honestly have the courage of their convictions to address the people who are on both sides of them, whereas, as the quick straw poll that I just took here says, hackers are unafraid of telling people on either side what exactly the problem is, and that hackers, as a general rule, carry the convictions of their beliefs much more readily than, I think, other classes of the population; that when hackers honestly believe that something is one way, they’re unafraid to tell people what that way is.

The other thing is, politicians are easily influenced by powerful interests. Really, when you look at political systems in modern Western democracies, the politicians are sort of stuck in the middle between the people that vote for them and the people that support them. And I think it’s very rare to find politicians who honestly have the courage of their convictions to address the people who are on both sides of them, whereas, as the quick straw poll that I just took here says, hackers are unafraid of telling people on either side what exactly the problem is, and that hackers, as a general rule, carry the convictions of their beliefs much more readily than, I think, other classes of the population; that when hackers honestly believe that something is one way, they’re unafraid to tell people what that way is.

And I think hackers, even though they might not have the reputation for doing so, are very good at cutting at the core of the problem and saying in very simple terms to people what exactly that is.

That’s another key thing about politicians: I don’t think politicians are very interested in looking at and understanding complex systems. They’re interested in taking little bits and pieces here and there and implementing those things in a small-little-bits-and-pieces way without really understanding what their changes could do and what the impacts of those changes might be, and what the impacts of those policy recommendations are or are not. Garbage comes in from bureaucrats who are trying to cut things down to make things simple and easy to understand, and lobbyists who are trying to get to one particular point of view or something like that across. And, of course, garbage comes in – garbage goes out.

Hackers, and I’ve noticed this in government and working professionally, will spend a lot of time looking at very technical details and trying to understand exactly how these systems work, looking at all the different things that go in and all the different things that might come out; playing all the different scenarios, looking at how all these things interoperate, and then arriving at a very good, almost intrinsic nature and idea of how all these things interrelate, and being able to make really good policy recommendations on those sorts of things, regardless of whether it’s code, regardless of whether it’s finances, regardless of whether it’s ways that the Internet operates.

Hackers are very good at understanding the entire picture and quickly relating their part of it and what power they have to do it, and what the consequences of those things are, and testing the consequences. I guess, as a quick aside, hackers have test environments where they can apply the certain theories and get it to the point where they work.

Government might not have the luxury of having a test environment, but maybe if we had hackers involved in politics, they would be more comfortable and more willing to take small segments of systems, run a lot of those policy changes, see what the impacts of those are, collect good data, and then make better policy recommendations across the whole system, based on what they find in their test environments.

Politicians fundamentally don’t know what a test environment is, and I guess we can see that now with a lot of the crises that just keep happening over and over again. I think hackers should be less prone to making those same mistakes than politicians are.

Common Features of Computer Networks and Government Structure

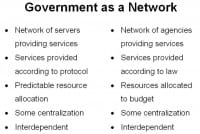

Another quick thing to sort of think about hackers and government: look at government as if it was a network system (see image). I’m hoping that in the discussion that will follow this people will start thinking of how government fundamentally looks like a network infrastructure.

Another quick thing to sort of think about hackers and government: look at government as if it was a network system (see image). I’m hoping that in the discussion that will follow this people will start thinking of how government fundamentally looks like a network infrastructure.

You wouldn’t normally think about it, because network infrastructures tend to be very ordered, discreet, running on the same policies, and government is this big nebulous bureaucratic thing that doesn’t really follow any kind of apparent logic or understanding.

But in a fundamental way, I think they are the same thing and you can look at them as the same thing. You have server farms that provide services to a user base. Governments have agencies that provide services to a user base. Networks run on protocols, run in predictable manners. Even though they might not share any kind of logic that is apparent to people, government agencies provide services according to a set standard and a set protocol. It might not be published, it might not be open – you know, there aren’t man pages for government agencies, but even still there is a fundamental guiding logic order in administrative law to agencies in Western democracies.

On a network side you have predictable resource allocation, you have fixed bandwidth, you have fixed power, you have a fixed number of people that you can serve with your given environment. Agencies and government as a whole follows those same constraints that resources are allocated according to the budgets that are given to a lot of these agencies.

Even though we might not like to think of the Internet as a centralized structure, in the ways that the Internet has failed recently, we can see that certain core problems in central areas can impact the entire network. It’s the same thing with government: if you have a failure in one central organization, that failure can cascade across many different agencies in unpredictable ways.

Networks have interdependencies; government agencies have interdependencies; everything is linked together. Even though government agencies might like to think that they operate independently, they are still all interdependent. And when you have failures in small parts of government, those failures can cascade up, whether the consequences of those failures are seen right away or not incredibly immediate. And that’s one key difference between networks and governments. When a network is broken, you know it right away; when the government is broken, the failures of that brokenness can tend to take a while to get implemented over time.

Different Approaches to the Same Problems

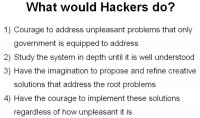

So, let’s take that sort of magical assumption that I made going at here: “What if one day we woke up, and instead of politicians in charge we had hackers in charge?” The first thing that I think would change immediately that you’d notice in the morning papers is that hackers would be courageous and say: “Look, I’ve looked at the books here; I’ve looked at the way these agencies function: there’s waste, fraud, abuse, we’re carrying a lot more debt than our ability to service that debt, and here’s what we have to do to address those kind of debts.” Hackers should be unafraid to just put it out there. And as we’ve seen with debt crises, both here on the European side and in the United States, politicians keep kicking the can down the road. And I think hackers fundamentally don’t do that.

So, let’s take that sort of magical assumption that I made going at here: “What if one day we woke up, and instead of politicians in charge we had hackers in charge?” The first thing that I think would change immediately that you’d notice in the morning papers is that hackers would be courageous and say: “Look, I’ve looked at the books here; I’ve looked at the way these agencies function: there’s waste, fraud, abuse, we’re carrying a lot more debt than our ability to service that debt, and here’s what we have to do to address those kind of debts.” Hackers should be unafraid to just put it out there. And as we’ve seen with debt crises, both here on the European side and in the United States, politicians keep kicking the can down the road. And I think hackers fundamentally don’t do that.

Another thing, regardless of what this current topic is or what the focus is: hackers like to study things. Hackers like to know and have answers to all of the questions that come up. And every little bit of knowledge that hackers discover spawns more questions. Hackers are good at consulting with other people around them; they’re good at knowing who knows what kinds of information, how to ask the right questions to get the information they need from those persons, and how to apply that information directly. I think, to be a hacker you have to have that little intrinsic understanding and ability to look at big complex things, not being intimidated by them; and study, and research, and look at things until you understand the way that those sorts of things work.

Another thing that hackers are really good at is having the imagination, after understanding these big technical systems, to propose creative solutions to them. We don’t see a lot of creative thinking in government; government does not encourage the kinds of people and the kinds of solutions that are completely revolutionary, that are completely out of the ordinary. People who work in government generally don’t have a big sense of imagination; they don’t have the courage to try things that are really off the wall, whereas all of the big products that we’ve seen coming out of the hacker community are really revolutionary solutions to things, coming from a sense of imagination that I think the larger population doesn’t have. Hackers are fundamentally more creative, more imaginative, and operate without the same kind of limits that I think non-hackers put on themselves.

When I was asked during an interview recently: “Define chaos,” I said: “Chaos is looking at the world without these sorts of limits, without thinking of the world as a very highly ordered, highly structured thing,” because the world is not a highly ordered, highly structured thing; it’s chaotic, it’s natural, it’s like nature, and we’ve created these large technical systems and economies that function in ways that we can’t control completely and that we can’t understand.

And I think hackers operate in that world of chaos; they know that there are things that don’t operate exactly according to plan. They know that there are fuzzy failures for sorts of things, and they know how to look at that and apply solutions and work in that environment. I think that sort of thinking is what we sorely lack in governments all over the world today. They are more interested in: “How do I patch the problem now? How do I apply more bad code, more bad laws on top of all the other bad laws?” They don’t think: “How can I get rid of all this cruft and create something that’s really good, that effectively utilizes resources, that is easy for people to understand?”

I think that if hackers came into government, they would look at code, they would look at tax laws, they would look at administrative law, and start saying: “That’s not right, we don’t need that, let’s get rid of it. We don’t need that, let’s get rid of it,” and get back to a system that functions as advertised, as it works, and have the courage to actually go ahead and do that.

The courage is something that I think politicians fundamentally lack. If politicians acted the way that hackers act – in the boardroom, in the cube farm, in businesses or in government – they wouldn’t have gotten to where they are, that governments in Western democracies operate in the way that encourages lies, that encourages deception, that encourages political expediency, that encourages kissing up to the person above you, not telling them the truth.

I guess politicians are the most brown-nosing, trying to find a way to not kiss a certain part of the anatomy, but that’s fundamentally what politicians do. I see this now: people who are young, who are just outside of college and getting into politics, are being trained from a very early age to be incredibly differential to power, to take the unpleasantness, put a little shine on it and present it to the person above them. And so people who are elected, people who become politicians, have had their entire careers working, essentially, lying to people.

I think successful hackers, on the other hand, get to be successful hackers precisely by doing the opposite: by telling the truth to power, by saying: “Look, your system sucks and you need to fix it, and this is how you fix it.” I think that’s how hackers become successful hackers.

Mudge, hacker from the Cult of the Dead Cow, who was the first image in my fun slide, was unafraid, went before Congress and said: “Yeah, if we felt like it, we could disable the Internet here in 15 minutes,” which was true then and possibly is true now. He knew he could do that, he had the courage of his convictions to know that he could do that, and he was unafraid of telling people that. And politicians were stunned; they didn’t know how to react; politicians don’t know how to react to somebody telling them unpleasant truth. And I think that’s something that today we desperately, desperately need.

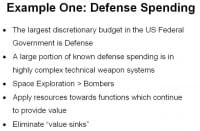

To get to more concrete examples, and I think this is an example that would be applicable to wherever you are in the political spectrum. The cold fact of the matter is: the cold war is over. We don’t have two opposing sides building increasingly technical systems to annihilate each other. That’s not the way war is fought today. The wars that are fought today are asymmetric warfare: you have large, centrally bureaucratized armies fighting small, decentralized guerilla outfits.

To get to more concrete examples, and I think this is an example that would be applicable to wherever you are in the political spectrum. The cold fact of the matter is: the cold war is over. We don’t have two opposing sides building increasingly technical systems to annihilate each other. That’s not the way war is fought today. The wars that are fought today are asymmetric warfare: you have large, centrally bureaucratized armies fighting small, decentralized guerilla outfits.

This isn’t exactly true in Germany, since we spend a lot more money on the defense of Germany than Germany spends on the defense of Germany, and that’s the thing when you look at the pie chart in government. There is this thing called “discretionary spending”. That’s spending that they have the option to do. A lot of social programs, social security and medic care in the United States are entitlement programs which people pay into.

Just a quick example: social security and medic care for retirees; people, whenever they work in the United States, pay a portion of their paycheck, and employers pay a portion of what they pay their employees into this system, so that when they retire, they get a check, they get health care at the end of their life. And that’s non-discretionary spending, because people pay into that system, and then they get those benefits at the end when they retire.

So, the discretionary budget is money that’s generated through taxes and through the issuance of debt that politicians have the option to control. In the United States, the largest portion in the discretionary budget is in defense spending. When you take apart the costs to maintain troops here and to do different things like that, the largest budget line items that we know of are in the defense department budget.

And that’s actually an important point to make, that a lot of spending in the defense budget is “dark spending” that they don’t publish the exact budget numbers on, because the going belief is that enemies of the state could extract intelligence information by figuring out where the government is spending that money.

But it’s still pretty well known where a lot of that “dark money” goes; it’s in building these incredibly complex technical weapon systems that, when you actually talk to people in the military, they say: “We don’t need them. We don’t need Stealth Bombers; we don’t need incredibly advanced fighter aircraft; we don’t need these huge ships that don’t work as advertised, that cost hundreds of billions of dollars in aggregate.” The military will tell you they don’t need it.

The reason a lot of these weapon systems exist is because they provide jobs to well-connected politicians in their districts. And the sad fact of the matter that the politicians don’t want to address, that these companies that are building these systems don’t want to address, is that you’re throwing money away into systems that don’t produce value.

When you build a big fighter plane, when you build a big ship, once you’ve finished spending the money on it, that ship does not continue to create value. The things that you build into these weapon systems are not discoveries, are not scientific innovations that you can take and apply elsewhere. Once you’ve spent 1 billion dollars on that plane, what’s that plane going to do? It’s going to fly around for a little bit, they’re going to train people how to use it, and at some point that asset is going to be retired, having created no additional value. When you build a bomb and put it on a plane, fly over something and drop that bomb, the bomb blows up; you’ve annihilated the value of the bomb and you’ve annihilated the value of whatever the bomb blew up.

When you build a big fighter plane, when you build a big ship, once you’ve finished spending the money on it, that ship does not continue to create value. The things that you build into these weapon systems are not discoveries, are not scientific innovations that you can take and apply elsewhere. Once you’ve spent 1 billion dollars on that plane, what’s that plane going to do? It’s going to fly around for a little bit, they’re going to train people how to use it, and at some point that asset is going to be retired, having created no additional value. When you build a bomb and put it on a plane, fly over something and drop that bomb, the bomb blows up; you’ve annihilated the value of the bomb and you’ve annihilated the value of whatever the bomb blew up.

The difference here, and we saw this in looking at the budget of the Apollo program, the Moon shot, what landed man on the Moon – all of the technical innovation that went into that program continues to create value today. The technologies that were developed in putting man on the Moon exist and are embedded in a lot of the technical systems and a lot of the things that we use today. And a lot of the advances that have come since then are because of those discoveries and because they were open. Even though that system was run by government contracts, a lot of the discoveries that were made in that time period were shared among a large group of people, which people continued to build on.

And so, I think, if you put hackers in charge of government, and you say: “Ok, you need to adjust the defense budget,” they would say: “Instead of spending all this money on advanced technical systems, on bombers and ships that we’re never really going to use, that are never going to fight, that add nothing to the defense of the country, knowing that we need to continue to create jobs for people in these politically connected districts, we will need to apply a lot of that technical money and a lot of that expertise into space exploration.”

I like to say this a lot: if you were a non-human intelligent species looking down on planet Earth, and you had a basic outline in the history of what was going on here, and then you said: “Ok, they made it to the Moon in the 1970s. 30 years later, they’re still just putting things in orbit around their planet.” I mean, think about how ridiculous that is to actually reach the Moon and then stop, and to not go back. Does anybody think that there is something fundamentally wrong with that? Who thinks that’s a little weird? I think that does not work and does not compute.

And if you had hackers devoted to spending time on things like that in government, it seems they’d be like: “No, when you reach an important milestone, you go on from there, you don’t just quit.” But the sad reality of that is that the defense contractors, politicians, people who are connected, people who are living in a world of lies and living in a world of political expediency, say: “No, we have to keep doing the same thing that we’ve been doing over and over again” – the core definition of insanity.

I think if you had hackers who are really looking at this problem, who are really providing leadership in government, they would take things like this, and they would say: “Look, we can’t continue. If we’re going to borrow money from all around the world, and if we’re going to borrow money from the people who are, essentially, buying the products that they make, and then refinance our debt through that, we’d say No, we have to eliminate these sorts of value sinks, and we have to provide funding to people who are actually doing incredibly great work on literally no budget, and sort of encourage that, and do those sorts of things; and instead of applying money to the same thing we’ve been applying money to since the end of World War II, we should be applying money and resources in things like that which continue to create value.”

Economics: Current Problems and Possible Solutions

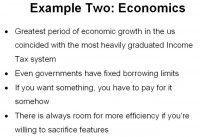

Now we’re getting to another point – economics. The greatest period of economic growth in the United States in the post-war era, and it closely resembles the “Economic Miracle” of West Germany and Italy in the post-war era, coincided with the most heavily graduated tax system in the US. And by that I mean people who make the most money were taxed at a much higher percentage than people who made less and less, and at a certain point you were not responsible for paying any taxes.

Now we’re getting to another point – economics. The greatest period of economic growth in the United States in the post-war era, and it closely resembles the “Economic Miracle” of West Germany and Italy in the post-war era, coincided with the most heavily graduated tax system in the US. And by that I mean people who make the most money were taxed at a much higher percentage than people who made less and less, and at a certain point you were not responsible for paying any taxes.

After Ronald Reagan, in the United States the tax system was heavily graduated so that it’s the people who were really in the middle, the people who had a decent middle-class earning to people just below what you would call rich, as the percentage of their income, paid the most in taxes. The people who were really rich, the people who were making money off of things like stocks, investments, and different things like that, wealth vehicles, have since the Reagan administration, as a portion of their income, paid less and less in income taxes in the United States – to the point where we’ve created an incredible wealth discrepancy between the people who were the poorest numbers of our economy and the people who were the richest numbers of our economy.

This is a problem, and I think that if you had hackers honestly looking at the economic impact of the tax structure in the United States, they would be unafraid to say this. And when was the last time you heard a politician say: “You know, the rich, really, are making too much money and they’re spending money unwisely: they’re sending money offshore, they’re putting money into luxuries and different things like that; they’re putting money into these vehicles that are, essentially, aspects of casino capitalism”?

You don’t hear politicians saying that; at least in the United States you hear people who are on the “Left Wing Fringe” saying that, and in the part of the political consciousness of the United States, these people are incredibly easy to ride off. The only thing you hear about in the United States increasingly is that rich people are taxed too heavily, which is not the case. It seems like the richer you are, the more things you have to get out of paying taxes than you do paying into the system.

And that’s something that I think hackers would address if they were looking at resources. Just looking at it as a sort of network problem, if the least parts of your network or parts of your system were hogging the most resources, what would you do? Rewrite the code so that these systems which are the very minority parts of the overall system, do not hog as many resources. I think that’s fundamentally what open software is all about: it’s creating more efficient, well-operating code so that you don’t have these sorts of things. Apply that same thinking to government, and you go back to what I think would be a much more heavily graduated income tax system.

Another thing which governments don’t like to address, and this is more relevant now in the European Union than I think it’s been in a long time, is that governments cannot endlessly borrow. One of the unfortunate things about the post-war era was the idea that governments could just borrow and borrow and continue to refinance, because sovereign wealth is “safe”, they are safe vehicles for investment.

I don’t really have to name the country in European room , to say that that’s not necessarily the case. And the worst part is that’s just really a bellwether. Germany has this problem; the United States has this problem that there is too much debt within the government. But unfortunately, it’s not politically expedient to point this out. Nobody likes to hear that we need to provide fewer services and charge more in taxes, but at some point the bill needs to be paid, and I don’t know the class of people in society that are more well-equipped to convey that difficult message than hackers are.

If you have built things and paid for things and you’ve wasted money, that needs to be paid back. But unfortunately we’ve had governments operating like teenagers with credit cards, thinking that if they default on it, then mommy or daddy is going to pay the bill. Unfortunately, there is no mommy and daddy above the United States Federal Government. Nobody can bail the largest entity on the planet out of its debt, and somebody needs to start saying that, but we’re not saying that.

And if hackers went to government, they would start saying that: “Look, we have a very serious problem and we need to start addressing it, and we need to start fixing it.” It just goes like the open source example that I said earlier: if you have fixed resources and all resources – economies, governments, entities – they’re all fixed in that way, they have a limited capacity, hackers understand what that capacity is, and they know exactly what they need to cut to fit into that capacity and to make things more efficient.

And so I think hackers know what it is to sacrifice features, and what it is to tell managers, to tell sales people: “Look, we can’t implement that; that’s just not possible.” Can you imagine how much better things would be in government if there were people there who operated like hackers, who were able to say that both to people who provide political patronage and to the people who are their constituents? Because hackers have to do that all the time: they have to talk to their customers and say: “This is not possible,” they have to talk to the sales people and say: “This is not possible.” They have to say: “Well, if you want this feature to be implemented, you have to do X, Y and Z.”

And again, hackers have to work within the limits that they are placed in. The sales people say: “Well, now you have to do it anyway,” and they’ll say: “Ok, it’s going to be really bad and it’s going to crash.” Then the sales people come back and they say: “This is really bad, it crashes” – “I told you it was going to do that.” Hackers are very well acquainted with that, and I think if they were doing that in government, it would be a good thing.

Environmental Issues and Changes to Adopt

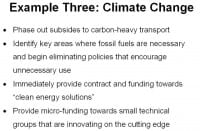

Quick disclaimer on the next slide (see image), I do have to say it to be completely honest. My current client is engaged in climate change policy, so I’m a little bit biased here. You might not agree with this, this might not be accurate, but leading to my final example, which I think is a really big, heavy problem – climate change.

Quick disclaimer on the next slide (see image), I do have to say it to be completely honest. My current client is engaged in climate change policy, so I’m a little bit biased here. You might not agree with this, this might not be accurate, but leading to my final example, which I think is a really big, heavy problem – climate change.

I think Europe is clearly a lot more progressive in this area than the United States is. But I think if you had hackers who looked at the evidence, both on the economic side and on the environmental side, and the impacts of fossil fuel-based transport systems on both sides of this, they would see that it’s limited, it’s going to run out, it’s creating problems for the environment, and we need to stop it.

I think that if you had hackers looking at budgets for transport, they would say: “These entities are clearly making a lot of money; they don’t need government subsidies.” Quick, done, that’s it. They wouldn’t pay attention to the fact that these entities didn’t get to make billions of dollars in profit without being incredibly politically connected. And unfortunately it takes big environmental disasters, like what we’re experiencing now in the Gulf region in the United States, to see: “Look, this is not right.”

But even in spite of a massive environmental catastrophe, they still enjoy an incredible amount of political power that the people who are engaged in climate change solutions don’t enjoy. And I think that hackers on either side of the divide would find that we don’t need to subsidize carbon-heavy transport. People on the right would say: “We don’t need to spend government money on people that are making a lot of money,” the people on the left would say: “We don’t need to subsidize all fossil fuels.” There is a lot of agreement on both sides.

Another thing hackers are good at is innovating and coming up with really advanced, good technological solutions. They’re out there, there are people working on them; they’re working on almost no budgets, more so in the United States than here in the European Union. But I think that any hacker would be interested in putting resources into coming up with things that work better, that are more efficient, that are radical solutions to these different things.

And unfortunately, we’re approaching the point where in our fossil fuel-based global transport network we’re going to need really radical solutions to a lot of these different problems. And I think hackers would be the kind of people who, if they were engaged in politics, would provide funding towards what we call: “Clean Energy Solutions”.

Another thing that hackers are good at doing is inventing a lot of these incredibly rich technical systems on little to no budget. And I think that if you put hackers in government, they would be able to identify which of those small outfits are producing good work or have the capacity or potential to produce good work, and apply funding towards them.

Unfortunately, governments are not really good at funding small projects: they fund larger entities that fund entities that are a little bit smaller that fund smaller groups, and so on and so forth. I think hackers, if they were in government, would be good at going from the top directly to the source of people who are working and doing good work and are creating a lot of these technical solutions.

So, that’s my pitch on hackers in government.

I suggest that we start a little bit of a discussion now, so I’m glad or take some questions.

Question: That all sounds extremely interesting; the only question I have is in what political system would you see that work, because in democracies we see all over the very same way politics work. For example, in Germany, the CCC is being consulted quite regularly by commissions before laws are enacted, only to find out that even if they make an extremely convincing point, the way it is redacted is complete bullshit. And it still gets voted, because the decision is not taken on the factual merits of the law, but on political dealings which take place elsewhere.

Answer: I think, fundamentally, any political system suffers that same problem, whether you have a parliamentary democracy or a one-party system. If people who are not interested in the truth are in power, they’re not going to listen to the people who are trying to tell them what they need to hear, and they’re not going to implement solutions based on that. You see this in Red China, you see this in the United States, you see this in the European Union.

And that’s the problem. I think politicians, regardless of whatever system they’re in, are experts in lies, deception, pacifying, whatever interest happened to be at bay, which is, I think, the core point here: hackers don’t play that game, fundamentally. Like I said, it’s a bit of the utopian solution, but I think the only way to really implement – and I’m not advocating violent revolution here – I’m pointing out the fact that we need more people who tell truth to power in whatever government we have.

And that’s the other part here: I’m not proposing that we kill all the politicians and replace them all with hackers; I don’t even think that would be a good solution. I think I just lost a security clearance there. I think politicians can’t be held more accountable as a rule, and unfortunately I don’t have a good quick fixer, easy solution; there are no real easy solutions. I’m just saying identifying the problem and saying that hackers are uniquely equipped to solve it.

Question: Ok, so my comments kind of go in the same direction, because I fully agree with what you’re saying about creating good policies regarding complex systems; that’s something hackers probably can do a lot better than politicians right now. But I’ve got this theory, and I’m probably going to get flamed for that now, but I think that hackers generally suck at democracy. There are counterexamples to this, like Debian, but generally, first of all – we can’t explain things. I mean, my sister doesn’t know what I’m doing. So, this is a problem. If you want to get votes, or if you want to be elected, you have to be able to explain what you’re doing, and most hackers I know suck at that, at least when they’re talking to an audience with lesser technical knowledge. And if we kind of self arrange, if you look at how hacker projects are self-arranged power structures, it’s generally something pretty close to being either a very weird kind of committee, or even a dictatorship. This is based on knowledge, and it’s a good thing, it’s very efficient, it’s great stuff, and it’s really cool if you want to create a piece of software, but if you want to create social equality, I’m not so sure.

Question: Ok, so my comments kind of go in the same direction, because I fully agree with what you’re saying about creating good policies regarding complex systems; that’s something hackers probably can do a lot better than politicians right now. But I’ve got this theory, and I’m probably going to get flamed for that now, but I think that hackers generally suck at democracy. There are counterexamples to this, like Debian, but generally, first of all – we can’t explain things. I mean, my sister doesn’t know what I’m doing. So, this is a problem. If you want to get votes, or if you want to be elected, you have to be able to explain what you’re doing, and most hackers I know suck at that, at least when they’re talking to an audience with lesser technical knowledge. And if we kind of self arrange, if you look at how hacker projects are self-arranged power structures, it’s generally something pretty close to being either a very weird kind of committee, or even a dictatorship. This is based on knowledge, and it’s a good thing, it’s very efficient, it’s great stuff, and it’s really cool if you want to create a piece of software, but if you want to create social equality, I’m not so sure.

Answer: That’s a valid point; I sadly don’t have too much of a response to that other than to say that hackers, I think, fail at bureaucracy, but I don’t think hackers necessarily fail at leadership. I think that hackers have that leadership potential. And again, when hackers are attempting to explain incredibly technical systems, they’re looking at very discreet code, small things, and explaining where it gets from code to function, whereas governments, even though they are incredibly dense and complex technical systems, I think people are more familiar and more comfortable with understanding the role of what government does and what it doesn’t. People look at the news and they read: “Government did this”. They don’t read that open source project X created this new library, or something like that. At least the hackers that I’ve seen, that are incredibly technically competent, are good at explaining how government works, if only because people are more receptive to it and to hear that. But otherwise, I think that the main point that you were trying to make that hackers as a whole tend to have certain failure points at democracy is absolutely valid.

Question: Hi Nick! Thank you very much for the great talk! I do agree that we need more hackers in government, because I think we need different mindsets in government. But I’m afraid I also believe that this would not be enough, because beyond that we would have to change the political system, because the political system we are facing, democracy, is a highly hierarchical and highly corrupt system. And I’m afraid that hackers, even if they have a nice mindset that suits better for problem solution, would get frustrated in that system and they would get sucked in and corrupt. So, I don’t see a solution for that other than fighting corruption and trying to make the political system more open and transparent. What’s your point on that?

Answer: I guess my point to that is: regardless of whatever political structure you have, once you give any set of people any kind of power, the tendency to abuse it and the potential for that grows. It really doesn’t matter on this system that people will, if you give them power without checks, tend to abuse it. The thing that I see in the hacker community is that sort of bigheadedness and the corruption that comes with an increase in power is not tolerated in the hacker community.

I don’t believe as much in the change of system as the change of outlook. I believe in more truth, transparency, openness; and hackers advocate for that. And I think hackers are the least susceptible group of people to the kind of corruption that power creates.

And it’s really system-interdependent; it doesn’t really matter what political system you’re operating under. Anytime you create ways of compensating for things like that, people will find ways around them. The political system in the United States was designed to sort of eliminate and create checks and balances on power. But as we’ve seen over the past 200-something years, people have found lots of little nice and easy convenient ways to talk around that, and to sort of circumvent the system controls that were designed in there.

Hackers, I think, understand circumvention of system’s rules and know how to identify them and how to patch for them. And that’s a strong reason I think that hackers would be good in whatever government you have in there, as long as they continue to hold and check and keep each other accountable. Next question?

Question: I think it’s not that simple. You can say: “Let’s put all the hackers in the government,” but I think there are still some problems you cannot solve that way. I think it’s a very complex system.

Answer: No, it is a complex system and I was proposing some policy solutions that were driven by hackers, but, like I said, nothing is really that simple. At best I was just trying to illustrate the difference between the politician’s mindset and the hacker mindset, and that when it comes to government, I think, the hacker mindset is more appropriate.

I also think that hackers, as a general rule, tend to get disgusted with politics precisely because it’s such a diametrically opposite way of thinking about things and looking at systems. And if anything, the only solution that I have for that is to just give it some patience. Think of it as a system that is uncooperative, that you don’t understand.

It’s interesting that if you give a hacker a piece of code that is not functioning correctly, that they don’t really understand how it works, they will spend hours, days, weeks, years trying to understand, trying to work it out, fuzzing the code, figuring things out. If hackers had that same patience for government, which, even though it doesn’t appear to be as logical a system and is not as logical a system, can still be treated in the same way if you devote time and resources to understanding it and proposing it. I’m saying hackers should have more patience with government to try to keep it more accountable and open, but aside from that, yeah, there are no simple solutions to anything. There are problems that evade complexity of many different types.

Comment: Thanks a lot for your talk! Just because I think it’s completely unrealistic, it’s actually über-romantic, I would call it, but that’s ok for a keynote, I like that.

Answer: You’re a Marxist, you would say that…

Comment: No, I’m not a Marxist specifically, but I can talk about that. Ok, my basic statement would be that I know people in the hacker community who do not talk to other people just because they use a different operating system – talking about democracy in the hacker system. The interesting thing about the hacker system is that it works because it’s a system based on reputation, and people are doing stuff here because they want to show that they are good, that there’s competition going on. It’s an interesting way, but of course, there is the same kind of not, like, corruption, but the same thing that you complained about in the political system and with politicians, happens in the hacker system the same way, but at a completely different level, because there is no actual money around, there are different other ways.

The power structures in the hacker community work not so completely different than the structures in the political system, I would say. And if you see the discussion of the Pirate Party in Germany here, you can actually see what happens if people from the hacker community end up in politics, and they fuck up even worse than the Green party in certain elements of what they’re doing. Still, I’m looking forward to see what will happen in the future with the Pirate Party, because there is a certain amount of possibility that it might work, but let’s see.

Answer: The only thing I have to say to that, with the respect to the Pirate Party in Germany, is that they are hackers operating in a fundamentally different system; they are not at the point where they’re a minority party cutting deals or becoming part of some kind of other coalition. They’re very focused on what their agenda is. I think they’re ignoring a lot of other things and they don’t have a comprehensive platform; that they’re very focused on the issues that they are focused on. I don’t necessarily think that it’s a bad thing, and yes, at the same time hackers don’t have the intrinsic knowledge for operating in illogical political systems. I think a lot of the critiques I hear are absolutely correct, and I don’t have a response for them.

For the hacking community, we invite you to come to the “Crack This” challenge and please let us know what you did or at the very least, endorse the challenge to your friendly hacking community! Thanks for your attention!

The software uses the IMPACT ( Indeterminate Morphic Poly-Alphabetic

Cipher Technology ) method, wherein a provisional application for patent

has recently been submitted. The initial key length is 65536 bits and

the encryption is One Time Pad based with a running key length of

65536*n bits.