Electronic Frontier Foundation representatives Marcia Hofmann and Seth Shoen participate in Black Hat Europe 2012 Conference to present their white paper on guidelines for maintaining digital privacy when crossing the U.S. border.

My name is Marcia Hofmann, I am a Senior Staff Attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in San Francisco. And I’m also a non-resident fellow at the Stanford Law School Center for Internet and society. And this is my colleague Seth Schoen, he is a Senior Staff Technologist at the EFF with me.

My name is Marcia Hofmann, I am a Senior Staff Attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in San Francisco. And I’m also a non-resident fellow at the Stanford Law School Center for Internet and society. And this is my colleague Seth Schoen, he is a Senior Staff Technologist at the EFF with me.

Seth and I, over the past year, have spent a lot of time writing about searches of electronics and digital information at the U.S. border. And we completed a paper in December 2011 which we published on our website [link]. So we wanted to do a presentation here at Black Hat to talk about our findings. A lot of people seem to be very interested in this subject, the question of what the U.S. Government can do at the border with digital devices and digital information. It turns out they can do a great deal, and that concerns a lot of people, it concerns business travelers, it concerns people who just really value privacy. This seems to be a real hot-button issue for people.

So what we’re gonna talk about today, first of all, is the legal situation at the border. Now, I am a U.S. lawyer, and what I mostly know is U.S. law, and so I’m gonna be talking mostly about the legal situation at the U.S. border. But I think it’s safe to assume that when you are traveling across other international borders, a lot of what we will be talking about is going to apply there too. And where I know there are certain issues that you should be aware of at other borders, I’m gonna do my best to flag that.

We’re also gonna talk about the policies and procedures that govern border searches at the U.S. border by component offices of the Department of Homeland Security. We will talk briefly about the considerations you might take into account when you are choosing a strategy for protecting your data when you are crossing international border. And then Seth is gonna talk a bit about some of the technical and common sense measures that we think people can take to protect their devices at the border. So that’s kind of how we’re gonna go with this.

The Original White Paper

Like I said, this talk comes out of this white paper that we published. I don’t know how many of you have read it. I hope that if you find our talk interesting, you will take a closer look at it because it’s certainly far more detailed than what we’re likely to get into here today. We’re gonna do kind of a basic overview of some of our findings, and if you are looking for more information in-depth, please take a look at that.

So Seth and I worked on this together. We decided to make this something that would have a legal perspective, and also a technical perspective. We had a great deal of assistance from an attorney named Rowan Reynolds who volunteered at EFF last year.

A very important overarching principle that I think we need to remember when we are talking about searches at the border is that it’s a very difficult situation that doesn’t have a whole lot of hard-and-fast rules. I think that border agents have a great deal of discretion to perform searches of pretty much anything that comes across the border – that includes things that you might pack in your luggage, but it also includes your electronic devices. And I think that if you get into a situation in which a border agent is interested in you for whatever reason, that can turn into a high-stress and sometimes confrontational situation, and I think that’s something that worries a lot of people.

The situation at the border is one where you are dealing with a government agent in a way that is unfamiliar. I think that many of us feel that when you are interacting with a law enforcement agent, there are certain rules that tend to apply: you know, there are some regulations on their ability to search things and to seize things. And I think a lot of people feel that when you are speaking with a government agent and they’re questioning you, you have a right to have an attorney present; and that’s true in many situations, but these are some of these familiar rules that, frankly, just don’t apply at the border.

The Law

So I’m gonna give a bit of an overview about the law that applies at the border. In the United States, the major constitutional provision that would be in place is the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees that “the people [shall] be secure … against unreasonable searches and seizures” by the government. What that tends to mean – you know, the general rule that we can take away from that – is that, as a general matter, the government has to get a warrant if it is going to search something in which you have a reasonable expectation of privacy, such as your property. This would include your personal effects, and your computer.

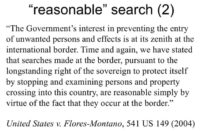

But there are circumstances where that general rule just doesn’t apply. And unfortunately, one of those circumstances is at the border. And the courts in the United States that have looked at this question have held that searches that occur at the border are just reasonable per se. And since the Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, what that means is that the government doesn’t have to get a warrant.

Now, why is that? The United States Supreme Court explained this a little bit in one of the most prominent cases on border search. You can see the quote here, and basically the idea here is that the government has a very-very strong interest in preventing the entry of unwanted people and property at the border. And this is something that goes back to the earliest days of the U.S. Constitution. So basically, because the government has such a strong interest in protecting itself from undesirable things and people coming across the border, it has a very wide-ranging authority to search and question people, and to examine their things that they bring across the border. And because that interest is so strong, virtually any search that occurs at the border is considered reasonable. The one exception that the Supreme Court has recognized, actually within this case (United States v. Flores-Montano) is the search of an individual’s elementary canal. So basically, that is the only time that the government even has to have a reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing, otherwise they can perform searches without any suspicion of wrongdoing whatsoever, meaning that they could even randomly stop you and search your things, including your computer.

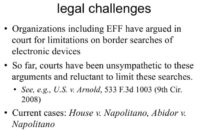

Various organizations, including ours, have argued in court that this is really too expensive, particularly considering the fact that electronic devices can potentially contain so much information about a person – certainly, proprietary information. You know, I am a lawyer, so I tend to think of things like privileged confidential client information. But often it would include personal information too, right? I mean your communications with your family and friends, and associates over time; your web browsing history; perhaps your financial and medical information. And it seems to really defy logic that that should all just be up for grabs when you cross the border. And I believe a lot of people think that shouldn’t be the rule.

The various organizations that have tried to challenge this in court have tried to argue, you know, a computer is nothing like a piece of luggage, and if you bring a piece of luggage into the country you are going to have some clothing in there and some personal effects, but it just pales in comparison to the things that the government can paw through in your digital devices, and the rules simply shouldn’t be the same just because it’s a personal effect.

But unfortunately, the courts have not been sympathetic to that argument, and they have held at this point uniformly that the government needs no suspicion of wrongdoing whatsoever to search your devices at the border. We cite here case called “The United States v. Arnold” which is the most recent and perhaps the most famous on this question. It was in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals which is considered one of the most liberal in the country. And in that case, the lower court (the district court) held initially that computers are just very special and different, and they present different privacy concerns, and therefore the government has to have at least a reason to suspect wrongdoing before they can search a computer at the border. But the Appeals Court disagreed and said: “No, if we look at all of the cases going back, there’s really no basis for that, and we think that the rule is the same as it is for luggage.” So no suspicion of wrongdoing needed, and at this point, unfortunately, the case law is pretty consistent on that point.

There are a couple of cases winding their way through the courts right now: one called “House v. Napolitano”, the other “Abidor v. Napolitano”. The “Napolitano” refers to Janet Napolitano who is the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, so she is being named in her professional capacity there as the defendant. And these are both cases that are being litigated by the American Civil Liberties Union, or the ACLU, and remains to be seen how those cases will turn out. We hope for a better ruling in those ones.

So that’s the situation at the border: basically, it doesn’t matter who you are, whether you are a U.S. citizen or a non-U.S. citizen, nobody really has much in the way of any sort of legal right at the border to protect the privacy of their things and their information.

U.S. Border Agencies

So let’s talk a little bit about what we know about agency policies and procedures for performing searches at the border. I think a lot of people find the structure of the Department of Homeland Security confusing, so we’re gonna talk a little bit about the various agencies that you may have heard of, and which ones you might be likely to encounter during a border search or border inspection.

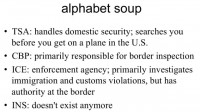

So DHS is the Department of Homeland Security; it is kind of the big overall blanket organization, or agency. These first three are components, the smaller agencies within the Department of Homeland Security (see image).

TSA stands for the Transportation Security Administration. Actually, when you cross the border you will not encounter this agency at all. This agency is responsible for conducting security inspections within the United States, and so if you happen to be in the United States and you are flying from one airport in the United States to another, then TSA is the one that will do security there. These are the ones that have the naked body scanners that everybody gets really upset about certainly; and these are the ones that will X-ray your carry-on baggage; these are the people who operate the magnetometers that you walk through – that’s TSA. You really don’t encounter these at the border.

CBP is Customs and Border Protection. These are the people who do the passport checks when you enter the United States. This is the agency that’s primarily responsible for border inspection. So chances are, most likely, that if somebody is going to inspect your computer, it may well be CBP.

ICE is Immigration and Customs Enforcement. I tend to think of CBP as kind of more bureaucratic agency, but ICE is more of an enforcement agency. They have authority to investigate immigration and customs violations, and violations of law at the border. So if an inspection escalates, it’s entirely possible that ICE might be searching a device. These are also people you might run into.

A lot of people ask about INS – that’s an agency that actually doesn’t exist anymore. It was pre-Department of Homeland Security, and now it’s been kind of wrapped into the DHS, and its functions sort of distributed to other little component agencies. But these are not people that you are likely to deal with anymore, because this agency doesn’t exist.

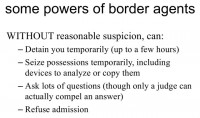

So here are some of the things that border agents can do without any suspicion of wrongdoing whatsoever. They can detain travelers temporarily (up to a few hours) for questioning. They can detain your possessions temporarily – this includes taking possession of a device to analyze or to copy the data on it. They can certainly ask you lots of questions, though only a judge can really force you to answer questions, and we’ll talk about that later. And they of course have the authority to refuse admission. And one of the most frustrating things about dealing with agents at the border is the fact that they have tremendous discretion to make these decisions. So if you ask a question: “What can get you refused admission?” – that’s a very difficult question to answer, because I think it depends on the circumstances and who you are dealing with. I think one agent might refuse admission, where another might not.

Border Search Policies

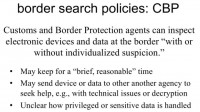

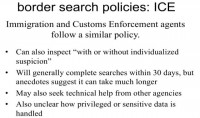

Both Customs and Border Protection, which is CBP, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which is ICE, actually have published policies that you can download and read, that explain and give guidance to their agents on how to inspect devices at the border. If you are interested in taking a look at these policies in full, you can actually just find them on the DHS website. Or maybe just google something like “CBP device inspection policy”, and you’ll come right up with the stuff.

So CBP’s policy makes clear that their agents can inspect electronic devices and data “with or without individualized suspicion” of the traveler. CBP says that they can keep a device for a “brief, reasonable” time which usually doesn’t exceed 5 days. They may send the device or copy of the data to another agency if they need help making sense of the data, i.e. if they encounter an encrypted version of data that they are trying to decrypt. If they are having some technical problems, or if the data happens to be in a foreign language which they can’t understand, they might seek assistance of another agency to help understand what they are reading. It’s worth noting that the policies don’t make clear what happens to those copies of the data that are sent to other agencies.

It’s clear that the policies anticipate that agents may run across sensitive data: things like medical information or privileged information, in one way or another. But it’s not clear what they do when they run across that data. Basically, the policies say, you know: “Be sure to talk to a lawyer, hire up in the agency if you need help figuring out what to do”. But the actual procedure for handling that information isn’t clear.

ICE’s policy is very similar. Again, they can inspect information or devices “with or without individualized suspicion”. They are required, as a general matter, to complete searches of detained items within 30 days, but we’ve heard stories suggesting that under certain circumstances that can take much longer. They also can seek help from other agencies, and it is, again, unclear how they handle privileged or sensitive data.

Interacting with Border Agents

We would now like to talk a little bit about how to interact with agents that you encounter at the border, given the fact that we know that they have expansive authority to search items. We think that one thing that is important to keep in mind is that they may be more likely to want to search an item if they sense that you are not cooperative. And so we would suggest, if you’re crossing the border, you consider avoiding giving agents excuses to become concerned about you, or concerned about your possessions. It is very important not to lie to border agents; that actually is in and of itself a crime. And, you know, if they ask you something like: “Do you know the password to this?” – and you say: “No” (while you actually do), that in and of itself can get you in so much more trouble than if perhaps you would just give it to them. It’s also important not to obstruct an agent’s investigation – that can, again, be a separate crime. We’re gonna talk about situations where these concerns may come up a little bit later. Also, I think it’s important to be polite to people, I think that they are likely to give you an easier time if you are trying to be gracious and professional about a situation. I really feel that you do not want to turn over information, but you should recognize that it doesn’t mean that you have to be obnoxious when you do it.

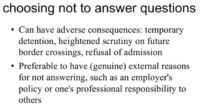

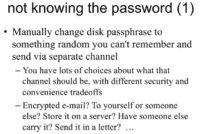

As I mentioned, you may choose not to answer questions. You should recognize that even if you technically may have a right not to answer questions, that can still have adverse consequences. It may lead to your questioning, whereas you may not have been questioned otherwise. In a really extreme circumstance, if you’re dealing with a very difficult person, I think it could even mean that you don’t get admission to the country. For this reason, Seth and I think that it’s worth considering whether IT policies might be put in place that would give employees of companies external reasons for not answering questions. Maybe you might have a situation where a border agent says: “Could you please give us the password?” And you say: “I’m sorry, I can’t do that because my company has a policy that says I can’t do it”. I think it feels much better, and it’s much preferable to be able to point to an external reason why you can’t do something or you’re not willing to do something that’s not just “I don’t want to”. And I think that may tend to make your interactions certainly more smooth.

Personal Background and Circumstances

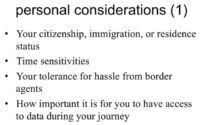

One thing that we realized was that there really isn’t one strategy that everybody should adopt for protecting data at the border. It depends a lot on you and your personal circumstances, and what your situation is. And so we think that it’s best to think through this in advance and figure out if you have some sensitive factors that might suggest that a certain strategy is more important than another.

One of the factors that we have identified as being potentially important is, for example, your citizenship, or your immigration, or residence status: do you feel like you are particularly vulnerable at the border? I think that United States citizens have an easier time getting across the border than those who are not United States citizens, and I think that certain people feel that they wouldn’t want to jeopardize, for example, their residency status by appearing too difficult at the border. So if you feel that you have certain sensitivities along those lines, it’s worth considering.

Time sensitivities are also important: do you need to be at a particular place at a particular time? If you are detained at the border and questioned, and you’re held up – is it gonna cause a big problem for you?

What kind of tolerance do you have for having difficult interactions with border agents? Do you want a situation where you’re bringing in encrypted data, and you’re asked for your password, and you’re saying: “No, I’m not giving it to you”, or would you feel better in a situation where they say: “We want your password”, and you say: “I don’t know it”? You know, if you are not being difficult because you don’t know something, that certainly, I think, takes some pressure off of you as a person.

Another question is how important it is for you to have access to data during your journey. I mean, could you consider bringing a blank device over the border and perhaps downloading data when you get there? A related question is how good your Internet access is when you reach your destination. Are you actually going to have logistical capability to download data if you want to do that?

Another thing that’s important to think of is the places that you visited on your trip before entering the country, because I think that certain countries tend to raise certain ‘red flags’ for border agents. For example, in the Arnold case that I mentioned earlier (United States v. Arnold) the defendant was coming back from the Philippines, and I think that raised the ‘red flag’ for border agents because they think that men coming back from certain countries may have been engaging in certain activities that they are on the lookout for. So that’s something to consider.

And then finally, your history with law enforcement: are you likely to get more hassle from border agents because you are of interest to them? We were contacted by a number of people who find themselves being a ‘watched list’ misidentification – do you have problems like that? These are things that are worth thinking about.

So now I’m going to turn it over to Seth, and he’s going to talk to you a bit about some of the precautions that you can take before you travel, and some of the technical strategies that you can use to protect data.

Technical Considerations

Seth Schoen speaking:Thanks Marcia! I think something that all travelers can benefit from is both keeping regular backups and encrypting the disks that they are taking on their trip. And I think these are two sides of the same coin because keeping backups is about making sure that you have access to your data, and encrypting your drive is about making sure that other people don’t have access to your data, which are both important security properties. And I think this is true even for reasons beyond border search privacy concerns, and even for people who don’t plan to refuse to tell their password to CBP if asked, for example. Because it’s very easy to lose mobile devices when you’re traveling, people often leave them in taxis. I had a friend who visited me from Brazil, and he managed to lose two mobile phones and a laptop during his trip in San Francisco, on the same trip, in about a week. So these things happen, and I just think, if you only lose one mobile phone or one laptop, it would be much better if that’s encrypted and you have a backup, because then you’ll have this peace of mind while you’re traveling that you’re not going to lose your only copy of something, and that strangers aren’t going to get that information without your knowledge.

And if you do feel that you are going to turn over your password if asked, you still have the advantage at the border that you know whether or not the agents have looked at your information – they are not going to be able to do it without your knowledge or without your cooperation. There’s also of course the possibility of using only online network storage and not carrying things with you.

So we have a lot of thoughts which we’ve talked about in our paper and which we are going to talk about very quickly here, about various ways of not carrying things with you as you cross the border. And of course there are quite a lot of permutations here, quite a lot of ways that you can arrange not to carry things with you. An interesting one if you have a laptop with an easily removable hard drive, or you like using DD, is to use a separate hard drive or a separate hard drive image for your trip, compared to the one that you normally use. Some laptops have hard drive bay right on the side. You can actually have two: keep one at home, use the other for travel. You can also sort of simulate that by making a byte-for-byte image, copy of your hard drive, with DD or with something like Ghost.

Another basic concept that’s becoming increasingly popular is to upload something in one place, and then download it in another place. There are some devices like Chromebooks that make this the default behavior. There’s also this important issue that if you aren’t separately encrypting the data that you’ve uploaded, then your network storage service provider will have access to it also, which could be a security vulnerability in itself. So it’s certainly preferable to pre-encrypt before uploading them to network storage provider.

I have actually met someone who would send her mobile phone in the mail, because she was very prone to being stopped at the border. She had had it happen several times, she had somehow attracted the interest of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and they would stop her on every trip. And so she reached this level of frustration and decided that she was actually going to send her phone in the mail before reentering the United States, and it’s a possibility.

It’s worth noting that things that you send in the mail or with a carrier like FedEx can still be inspected by customs when they enter the country. There’s an interesting question about the circumstances under which they can open letters; I think our conclusion was that under some circumstances they can even open letters, although it’s much more constrained by policy than opening a parcel or package that has a customs declaration. But the big advantage of course to sending something in the mail is not that it won’t be inspected, but that you won’t be getting questioned by Customs and Border Protection at the same time that the thing is being inspected. It will eventually arrive, hopefully; and you won’t have people saying: “What can you tell me about this device you’re carrying with you? Can you unlock it for me?” and so on.

We also think that Customs and Border Protection has no authority to alter or bug equipment without getting a warrant to do so. So we think that as a general matter they can’t just say: “Oh, that’s interesting, this person is mailing a laptop into the country, let’s just put a bug on it”. We don’t think that that would be permitted by law.

Creating a Strong Password or Passphrase

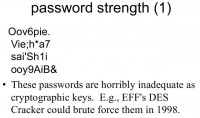

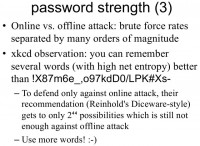

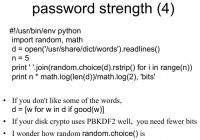

I wanted to talk really quickly about password strength for full disk encryption. I think it’s a topic that a lot of people are probably already familiar with. You may know that EFF built a machine to crack the Data Encryption Standard back around 1998. So our non-profit organization was able to crack 56-bit keys in 1998. These passwords here are all about 56 bits or entropy, so it’s very likely that the government can crack them if it’s so inclined.

In fact, there are rainbow tables for password cracking. And depending on how your disk crypto implements key derivation, it’s likely that you may not be able to remember a long enough random string to get outside of the rainbow tables that have been published.

The government may have better cracking capability than you, and so there are a lot of ideas for ways to choose a good passphrase, there are lots of resources on this. There’s a technique called Diceware from Arnold Reinhold – it’s basically a technique for choosing random words. If you actually do the calculation – there was a great xkcd panel about this sometime last year – you can see that choosing a small number of random words can give you as much entropy in your passwords as choosing some unpronounceable string. So here’s an unpronounceable string that’s very hard to remember (see image to the upper right), and if you had just a few really random words you could actually reach a similar entropy level, and you might actually remember them.

Okay, if you think random.choice () in Python chooses good random numbers, you can choose random words out of a dictionary, find out how many bits are in your passphrase.

I think passphrase strength is something that people are becoming fairly familiar with, but it’s a good thing to keep an eye on. Of course there are systems that are using key derivation, or key stretching, like PBKDF2, where they’ll do some expensive thing to derive the actual crypto key from your passphrase, and that makes brute-force attacks a lot harder. My advice is if you don’t know how your disk encryption system uses key derivation, then you should cheat it as if it doesn’t, and make sure that you use an adequately strong passphrase to resist brute-force attacks.

I think I’m gonna hand it over to Marcia to talk a little bit about the question of: if you have this great passphrase that you remember and you know it, and you’re coming across the border, and they say: “So, would you mind unlocking your disk for us?” – what will happen then?

Requests to Decrypt at the Border

Marcia Hofmann speaking: Okay, we get this question a lot, and this is something that I think deserves a little bit of time. In the United States we have a constitutional amendment called the Fifth Amendment, and among other things, it says that you can’t be forced to be a witness against yourself. The origin of this constitutional right is the days when the authorities would torture people to turn over information about themselves. And this is basically intended to ensure that if the government is going to prosecute you for something, the evidence that they get is not something that they force you to reveal to them, that only you know – but rather evidence that they collect in the course of their investigation. So basically, they can’t make you give them the information that they are going to use to go after you.

So this is the rule in the United States, and in order for you to have this protection, three things need to be present. First of all, the government has to compel you to give testimonial evidence against yourself, and when I say ‘testimonial’ what I mean is it needs to be something that’s in your mind. They have to be forcing you to turn over something that you know, that isn’t memorialized anywhere and that isn’t physical evidence. And the last thing is it would have to tend to incriminate you, and when I say ‘incriminate’ what I mean is not something that shows evidence of your guilt, but something that they might use to bring a prosecution against you. It doesn’t need to be direct evidence itself, it could be something that’s just a link in the chain that would tend to incriminate you.

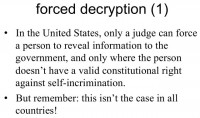

So if you have a situation where there is something on your computer that might tend to incriminate you, you may very well have a valid Fifth Amendment right not to turn over that information. It is very important to know that this is not the case in all countries, and there are several countries, in fact, that have key disclosure laws, where the government can force people under certain circumstances to decrypt data or to turn over encryption passphrases. Some of these laws are in, for example, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands has one, France has one, Australia, Canada, Finland, Belgium. And so, if you are taking encrypted data somewhere and you know your encryption passphrase, it’s important to know whether or not a country has such a law.

I also understand that Russia and China require people bringing encrypted data into those countries to seek permission of the government to do so. So I think it’s also important to consider whether or not you are going to a country that has a law like that.

So even if you have a valid right not to turn over information, you should be aware that refusing to provide that information could still have adverse consequences for you. For example, it may lead a border agent to conclude that you’re difficult, and it could lead to questioning or even in a very extreme case refusal of admission. So it’s important to think before your trip about how you would deal with requests to decrypt information. And, again, I mentioned before that we think an IT policy could be helpful in certain situations, and this is one of them.

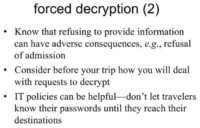

You could have a policy where your employees actually don’t know their encryption passwords while they’re traveling, and they only learn them upon reaching the destination. So I think that puts them in a much better feeling position if they are being asked to turn over an encryption password, because they can simply say: “Listen, I honestly don’t know it.” You’re not lying, and there’s nothing you can do, and I think that in some circumstances that might be a pretty decent solution.

Okay, I’m gonna turn it back over to Seth.

Seth Schoen speaking: The idea of not knowing your password, I think, is a very interesting one. It’s one that I’ve been thinking about a lot. I should say it’s not clear yet how readily border agents will believe you if you tell them the truth that you don’t know the password to your own computer. They are probably much more accustomed to people actually knowing their own password, because that’s certainly the common case. So there is this question of whether they believe you, but certainly in terms of the ability to truthfully refuse to cooperate because you are simply unable to give them the information that they want. It seems like a potentially powerful tactic.

So if you don’t have an IT department doing this for you, you know, one way you can do it for yourself is to change your disk passphrase to something that you can’t remember because it’s a random thing that’s not memorable to you, and send that in some other way. And there are lots of choices about what that other way could be: encrypted email, giving it to someone else who is traveling separately – lots of possibilities.

Precautions against Border Searches

Now, I’m traveling from the United States, because I live in the United States. So when I am on this trip, I’ll be going home to the U.S. And I personally am concerned about border searches and taking precautions against them. According to the statistics that the American Civil Liberties Union obtained from the government under the Freedom of Information Act about how frequently border searches of electronic devices occur, it came out to about 300 per month, which is very few in terms of the number of people who enter the United States. That data was for October 2008 to June 2010 time period.

So on the one hand, searches of electronic devices (you know, intrusively looking through what people have on their computers) are actually extraordinarily rare as a proportion of travelers. At the same time, I personally know three people to whom this has happened, and so it feels like a very concrete and real possibility to me. I feel that it’s not random, and it feels like a real thing to me because I know these three people who had this happen to them, in some cases on multiple occasions, not just once.

So I’m interested in experimenting with precautions that I can take. I’m gonna talk about the approach that I’ve chosen to try on this particular trip to the Nethrelands. I use Ubuntu, so I have full disk encryption using LUKS, and LUKS has a concept of key slots. So you have the ability to have up to eight different passphrases, any one of which is valid, to decrypt your hard drive. So what you can do is as follows: I got my original passphrase, and it can generate a totally random and non-memorable thing, and then add that thing as an additional passphrase in a secondary key slot. And then there are two different key slots, each of which has an independent passphrase. Then, if I have some way to have or get the non-memorable one at home where I’m returning to, or to my destination in the U.S., then, skipping a few details about LUKS trying to prevent you from locking yourself out of your own computer even if you wanted to, you can kill the original slot that contains your original passphrase, and then you no longer know the passphrase to decrypt your drive.

I’ve actually done that on this trip, I have a passphrase that I left at home in the United States that I don’t know and can’t remember, and when I’m going to cross the border, before doing so I’m going to kill the key slot on my laptop that contains the passphrase that I know. When I return home, I have access to another passphrase that will be valid, but I won’t have it at the time that I’m crossing the border. So that was actually relatively easy to set up, it’s an interesting possibility. I’ve tried other encryption possibilities, other approaches at other times.

Is it possible that you could be compelled by a judge to turn over that password to decrypt? Well, one distinction is that the judge compelling you to do something requires you to be implicated in an actual criminal investigation. I don’t mean that you have to be the suspect, there has to actually be a specific criminal investigation about a specific crime in order for the judge to compel evidence to be turned over within the U.S. And this is different from the situation at the border, where they can ask me just because they feel like it, just because I happen to be crossing the border. So it’s absolutely correct that by having my passphrase written down I have lesser legal protection than I ordinarily would at home in the U.S., in the sense that any Fifth Amendment right that I might have no longer applies to prevent me from turning over that piece of paper.

On the other hand, compared to the border where no suspicion and no reason whatsoever is necessary, I still have relatively greater protection.

Marcia Hofmann speaking: Yes, I agree. And I think the key to this is – remember that I said that the Fifth Amendment right applies in a situation where they are trying to compel something from your mind, so that’s kind of the key there. If they happen to know that Seth had written down his password and they wanted to obtain a warrant to seize it, then that wouldn’t be a Fifth Amendment issue, but rather a Fourth Amendment issue, and in theory they could do that.

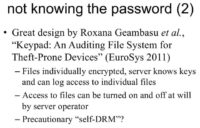

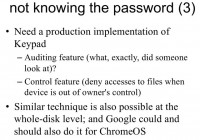

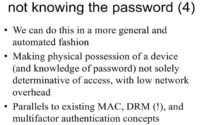

Seth Schoen speaking: So there’s this great design called “Keypad”. I don’t know if any of you have read this paper “Keypad: An Auditing File System for Theft-Prone Devices” from the University of Washington. I really admire this design, unfortunately they have not released their code, so I’m actually quite interested in re-implementing it. This is an alternative way, among other things, of not knowing your password. And it also provides a lot of advantages if your device is lost or stolen, not just at the border but at any time. Strangely enough, this is sort of like a digital rights management system, except that the person whose computer it is ultimately does have access to the keys. They ultimately can decrypt, and they ultimately can export files from the system. But every time they want to access a file, they have to request a decryption key for that file from a server. Under normal circumstances, where the person is in possession of their device, the server will automatically grant the decryption key and allow the person to read their files. But under exceptional circumstances, such as if the device has been lost, or perhaps if the person is currently crossing the border, the server could be programmed not to grant those keys, and therefore the device would be unable to read those files.

Anyway, these researchers from the University of Washington implemented this. They’re particularly interested in benefits for people like doctors who have a lot of sensitive information and obligations to tell people if that information is lost or stolen. And in this way, they can say, well, if the device is lost they can turn off the key server and say – no further accesses to the files on that device will succeed. It’s also potentially relevant in a border context, so I would love to re-implement this, and I think Google should do the same thing in Chrome OS, and I think it’s very feasible to implemented exactly this kind of things in Chrome OS.

In general, we can get into these concepts about mandatory access control, and in a sense about digital rights management, even though in this case it’s really for the protection of the end user and not to ultimately limit their ability to use files in the way that they want to – by implementing systems where physically possessing the device is not the only thing that you need in order to have access to read the files on the device. So I think there are a lot of possibilities for that.

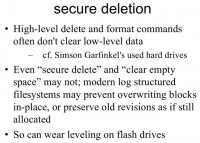

Special Considerations

I just wanted to say briefly that it’s relatively hard to delete stuff, and forensics is relatively effective. There are a lot of examples of that. You may know about Simson Garfinkel’s experiment with a bunch of used hard drives. He went and looked at what was on these used hard drives that had been decommissioned, and he found that very often people had attempted to delete the things on the hard drive before selling it and had not succeeded because they had used their ordinary Delete command, or they had used their ordinary Format command, and they did a high-level Format or a high-level Delete, and it didn’t overwrite the blocks actually containing the data. And so very often deleting things doesn’t work, and file systems are getting more advanced, so even “secure delete” may not actually overwrite the blocks with data. This is a frustrating problem.

Researchers who have looked at this generally say that the main answer is full disk encryption, because we really don’t know if we have some kind of log structured file system, whether the blocks that actually contain your data have been cleared when you erased things.

Also, wear leveling on flash drives is hilarious because the device actually writes your data somewhere unpredictable that you don’t know, on the physical device. And it doesn’t guarantee that overwriting the same block will actually overwrite that same block, because it says something like: “You surely don’t want to write to the same place on the drive multiple times”.

I think even Gutmann says that Gutmann’s advice about multiple-pass overwriting is obsolete. Single-pass overwrite is probably enough and has the advantage that you might actually do it, whereas you might not wait around for 35 overwrites. This is safer than securely deleting a file because the structure of the file system doesn’t matter.

Researchers from the University of Washington published this forensics paper where they say that people who are using partial volume encryption, not full disk encryption, often have leakage, where their operating system or their applications leave traces of the data from the encrypted volume outside of the encrypted volume. A really simple familiar example is that a word processor like Microsoft Word may auto-save, so you might have a TrueCrypt volume and you might have all of these things inside the TrueCrypt volume, and then edit them in a word processor – and it might auto-save outside of the TrueCrypt volume, and then erase the auto-save file; but the auto-save file can be undeleted. So this is a strong argument for preferring full disk encryption where possible. We don’t really have applications and operating systems that do this kind of secure compartmentalization very well on PCs.

Device-Specific Considerations

Mobile devices are even worse because forensics on mobile devices is awesome, and counterforensics on mobile devices is horrible. Most mobile devices that you might get have no full disk encryption option; of course there are exceptions to that. Most mobile devices have no secure erase option – if they don’t come with one, it’s often quite difficult to add it yourself, especially if you have a device that doesn’t give you root access.

Law enforcement and all kinds of forensics professionals have extremely powerful forensic tools that are extremely automated, that work on mobile devices. They can often just plug the device into a bay – and have the entire contents of the device come up on their PC immediately. So mobile devices are rough.

Cameras are also kind of electronic devices that could be subject to search. And like your mobile phone, they generally won’t have a secure delete option. In fact, there are lots of funny stories about how, if you erase a photo on a camera and if you then put your compact flash disk into a PC, it’s generally just deleted on a FAT file system, so you can run an ordinary Undelete program on the compact flash disk, and undelete the photo. That’s a common case. So if you had compact flash or SD cards that you wanted to clear, you might want to actually put them into a PC and actually overwrite every block, rather than just doing the Delete photos in the camera.

Marcia Hofmann speaking: I think we have a few minutes for questions…

– If I am forced to give my password that’s also my Google Account password, are they going to see only what’s on the device, or also look at my personal online details as well?

Marcia Hofmann: This is a very interesting question. I don’t think any court has ever looked at it. Our possession certainly would be that they would need a warrant to access anything in the Cloud, but I don’t know what the government’s position on that would be. And I suspect we’ll be seeing a case like that in the near future.

Seth Schoen: There are anecdotes about border agents and law enforcement agents in some countries asking people for Cloud service passwords and social networking passwords. And it does seem like in the U.S., at least in a non-border situation, there would be a lot of legal restrictions on the U.S. Government’s ability to use that to go log into your account, because there are lots of statutes that protect those accounts. But as Marcia said, I guess this has never exactly come up in a case arising at the border.

– If I have an encrypted personal file on my electronic device, would it be something acceptable to deny if the border agent says: “I want your password for that”?

Marcia Hofmann: I think it’s possible. I think one of the things that’s very difficult about thinking through these scenarios is the fact that you never know what a border agent would do. You know, we’re dealing with human beings, and one border agent might suggest such a thing and find that acceptable, whereas another might not. I’ve heard anecdotally about a situation, for example where an individual was bringing encrypted data into the United States, and the border agent said: “Give me your password,” and the person said: “No” – and the border agent said: “Okay, that’s fine, just go.” I think that of course that’s like everybody’s sort of dream scenario on such a thing, but my point is that you never know what a border agent is going to do or what they’ll say. And I think the suggestion you proposed is plausible, but I just don’t know how a border agent would react for sure – you know, one border agent’s reaction may be very different than another’s.

Seth Schoen: And it was very clear from reading the published policies from Customs and Border Protection for example, that at least the public policy does not tell the agents how to handle that situation; it doesn’t say that the agents can be that, and it doesn’t say that they can’t be that.

– Do U.S. citizens always have the right to return to the country, or can they also be denied admission?

Marcia Hofmann: This is interesting. When we were doing the research for this paper, we operated on the assumption that U.S. citizens have an absolute unqualified right to enter the country. And as we were tracking down different cases, there was basically one case from Puerto Rico, from 1968 that just kind of says that, but doesn’t cite any legal authority for it. And then there’s one case that comes up after that, again, just kind of glibly says it. So we were not able to pin that down as well as we would have liked. And it actually seems that the legal situation there is a bit unclear.

Seth Schoen: So there’s no court decision that directly questions it. But there’s no Supreme Court decision, for example, that clearly says that U.S. citizens have the right to enter.

– Just out of curiosity, is there any difference in the mode of entering the country in terms of these guidelines and procedures?

Marcia Hofmann: I don’t know… I honestly don’t know the answer to that question. Anecdotally, it seems to me that when you enter the United States over roads, when you’re driving a car, you hear quite a bit about situations where people are asked to turn on their laptops, and agents look at what’s on the laptops. I hear about that sort of thing much more often actually than people entering the country through airports, or on ships. But I have never seen any empirical data on that question, and I don’t know the answer for sure. Seth, do you have any idea?

Seth Schoen: I definitely have a sense that different ports of entry vary a lot in terms of the attitudes of the CBP agents working at them, in terms of what kinds of technical training or skill they have, in terms of the volume of travelers that they have; but I don’t have any concrete idea how to give a rule, like it’s better to come by boat or something. I know I’ve entered the U.S. by boat and by plane, and it varied a lot more from airport to airport, I thought, than between boat and plane specifically. Maybe in the future there will be some of Yelp reviews of ports of entry, giving the number of stars and reviewing the agent. I mean, it really does vary a lot. As a U.S. citizen who has reentered the U.S. a number of times, I’ve had CBP agents who didn’t even speak to me, who just looked at my passport, saw that it was a U.S. passport, stamped it and handed it back to me – and I was done. And then, I’ve had people who questioned me about my work, and one person at one point who even tried to question me about my political views because he learned that I worked for EFF. That was the most disturbing. So, you know, there’s quite a range certainly.

Marcia Hofmann: So I think that our time’s up. Thank you so much!

Tips for Dealing with Border Agents

- Avoid giving border agents excuses to get curious/alarmed about you and your possessions

- Do not lie to border agents

- Do not obstruct an agent’s investigation

- Do be polite to them