Morgan Marquis-Boire, Security Engineer at Google Incident Response Team, analyzes the digital aspect of activism and anti-dissident activities during the Arab Spring.

Hello and welcome to CuteCats.exe and the Arab Spring. My name is Morgan Marquis-Boire and I work on the Google Incident Response Team. Today, however, I am not here to talk about Google, but to discuss what appears to be the systemic use of phishing and surveillance malware as a means of suppressing dissidents during the so-called Arab Spring.

Hello and welcome to CuteCats.exe and the Arab Spring. My name is Morgan Marquis-Boire and I work on the Google Incident Response Team. Today, however, I am not here to talk about Google, but to discuss what appears to be the systemic use of phishing and surveillance malware as a means of suppressing dissidents during the so-called Arab Spring.

Before I start, I’d like to point out that this is work that I’ve done mainly with the Electronic Frontier Foundation in San Francisco and with the Citizen Lab, which is a human rights, digital media and global security think tank at the University of Toronto.

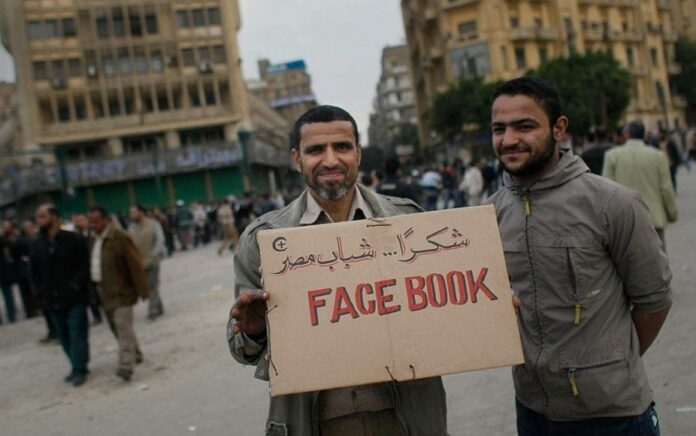

So, without further ado – CuteCats.exe and the Arab Spring. The title of this presentation refers to a revolutionary way of demonstration and protest occurring around the Arab world that began in December 2010, and also to a theory developed by Ethan Zuckerman in 2008.

Mr. Zuckerman postulated (see left-hand image) that most people are not interested in activism but mainly use the Internet for surfing pornography and lolcats. The tools that are developed for these activities, such as Facebook, Twitter, Blogger, etc., are nevertheless very useful to social movement activists who lack the resources to develop dedicated tools themselves.

So, he then goes on to stipulate that, subsequently, this makes activists more immune to reprisals by governments, than if they were using dedicated activism platforms, because messing with people’s cute cats and pornography provides a far greater outcry than shutting down obscure activist resources.

My corollary theory, which is the CuteCats.exe Theory of Digital Activism, is that once a platform attracts a critical mass of activists, that platform will be used to target them.

So, I’m sure many of you heard people describe parts of the Arab Spring as the Twitter Revolution or the Facebook Revolution. I don’t necessarily agree with those phrases, but they reflect the usefulness of the platforms Ethan Zuckerman describes in the organization of social movements. People that orchestrate surveillance campaigns are also familiar with this idea. Unsurprisingly, the targeting of dissidents across civil countries involved in the Arab Spring has played on the usefulness of Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Skype and other popular platforms.

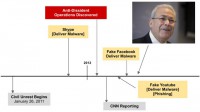

As everyone is probably well aware, there has been an extended period of unrest in Syria. Protests began in January 2011 and spread into a nation-wide uprising. Since then the Assad regime has deployed the Syrian army to quell the uprising, besieging several cities, however, as of the present day, this conflict is still ongoing.

Shortly after the beginning of the physical conflict a digital campaign was started against the opponents of Assad’s regime. While this was not publicly unearthed until 2012, evidence points this campaign starting in November 2011 or earlier.

Around Christmas of that year a group of activists providing technical support to the uprising were arrested. One of those who remained unimprisoned received a Skype message from one of his friends who had been captured advising him to install a useful tool, which would enable him to disguise his online identity from the regime surveillance. Unthinkingly, he installs the software and then realizes upon reflection that this was probably not a great plan (see right-hand image).

He called to external agencies for aid, and the analysis of his machine revealed that it had been infected with a remote access Trojan, which provided significant capability for surveillance of its victims. It allowed for logging of keystrokes, streaming remote view of his desktop, the ability to watch him through his webcam and listen to him through his microphones, as well as execute arbitrary programs. In addition to this particular Trojan, the machine was found to have been twice previously compromised several weeks earlier by the same actors.

Analysis of his computer and malware continued through January, and on February 17 CNN announced that computer spyware was the newest weapon in the Syrian conflict and discussed the widespread hijacking of activists’ accounts and credentials, as well as the targeting of dissidents.

Since this article, we have been able to track multiple persistent campaigns targeting opponents to the current regime in Syria. Their preferred methods involved targeting dissidents via Skype accounts of compromised friends, as well as targeting them through social networks used to organize the revolution.

For instance, Facebook is a platform that was banned in Syria until February 2011. It has many pro-revolution forums and profiles of prominent members of Syria opposition. In early April the Facebook page of Burhan Ghalioun, a professor at the Sorbonne in Paris and the leader, at the time, of the Syrian opposition transnational council was hit with a phishing attack.

This leads to almost 6000 friends and any visitors to his page being led to this website (see right-hand image). So, this is obviously designed to look affiliated with Facebook and offers a download under the words “Facebook security”. Unsurprisingly, this download is malicious software with keylogging functionality.

The malware was hosted on this (see leftmost image below) compromised site, which was found to be hosting multiple Facebook phishing campaigns by the same actors, such as this one (middle image below) and this one (rightmost image below).

While their campaign is noteworthy both for compromising Burhan Ghalioun and the terrible ability to mock up Facebook pages that don’t look really legit, there have actually been a lot of campaigns hosted on hacked websites that have been documented over the last few months.

While we’ve seen a steady stream of Facebook phishing attacks, we’ve also seen attacks focusing on Skype and YouTube. Many of you may have heard of the alleged recent suicide bombing of three senior military officials in Damascus. This campaign came out a couple of days ago. Emails were sent to Syrian pro-revolution mailing lists alleging that the site (see right-hand image) contained the final phone call from the Minister of Defense to his wife. It’s been made to look like a Skype site, and when you click on this picture it asks for your Skype credentials.

So, topical social engineering has been a feature of these campaigns. Earlier this year in March someone started seeding pro-revolutionary forums on Facebook with these types of messages (see left-hand image). It says: “Urgent and critical video leaked by security forces and thugs. The revenge of Assad’s thugs against the free men and women of Baba Amr and captivity taken to ends raping one woman by Assad’s dogs. Please spread this”. Clicking that link leads you to a fraudulent YouTube site.

A noteworthy feature of the Syrian revolution has been its use of YouTube. There have been many videos (see right-hand image) posted from the conflict detailing the ongoing violence occurring in Homs, Hama and other cities. The ability to display to the world the conflict occurring in the country, with foreign reporting largely banned, has been extremely important.

As you can see, this is a somewhat accurate mock-up of the pro-revolution Syrian channels that sprang up over the course of the uprising, the major difference being that the site was hosted on the server of a hacked British hosting company.

On visiting the malicious website, the users would be asked for their credentials in order to be able to post comments, and the site would inform the users that in order to view videos they would have to upgrade their Flash software. Naturally, this Flash software was malicious and installed the surveillance malware I mentioned earlier, allowing remote listening and viewing of activities via their computers.

This malware sent back the data to command and control domains inside Syrian IP space. And it’s worth noting actually that all the campaigns that have been documented so far have exfiltrated data into Syrian space, many of them to the same IP address. While this aspect of the campaign is not so stealthy, some of the social engineering employed has been quite compelling.

This campaign (see right-hand image) featured malware which used the overwrite trick recently used by the Madi malware to masquerade as revolutionary plans for the formation of the High Council after the revolution. Naturally, these documents installed a remote access toolkit. However, they also displayed documents to the user, which were purportedly intriguing and enticing and likely to be passed about by activists interested in their veracity.

Another campaign by the same actors pretended to be a Zero-Hour plan for the city of Aleppo (see left-hand image). Again, the purported documents installed the Trojan. However, they provided extensive documentation likely to be distributed by dissidents among their networks.

Skype is used quite extensively by activists who distrust the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. At the beginning of May it was widely reported that Skype leaked your IP, and by extension could potentially allow the tracking of your physical location.

Playing on the concern of dissidents, the same actors began distributing Skype encryption software (see left-hand image) which would allegedly alleviate this problem. Note that this software doesn’t actually encrypt phone calls. In addition to displaying a GUI with tragic abuse of Comic Sans, this installs the same surveillance malware.

This malware was Darkcomet. This is a remote access toolkit that became associated with the Syrian revolution. Perhaps because of this the author of it announced a couple of weeks ago that he would stop producing and distributing it.

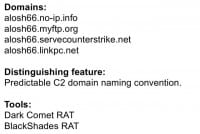

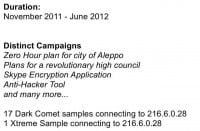

At the similar time, although not necessarily because of this, we’ve seen these groups in Syria move to the use of Blackshades RAT. Since the demise of Darkcomet, we’ve seen three variants of Blackshades, and they were all used by someone not very inventive when it comes to naming. This group used alosh66 as a prefix for four of these CnC’s (see left-hand image). Distinguishing feature: predictable C2 domain naming convention.

While they’ve been using Blackshades a lot recently – in fact, I saw a new sample of it on Monday, they’ve previously been using Darkcomet, and these people being the same actors who performed the fake YouTube attack that I mentioned earlier.

As I mentioned before though, the heavy use of Darkcomet has been a feature of the pro-regime electronic actors in this region, particularly these guys (see left-hand image). Again, inventive name; I’m not sure whether this group is related to the one I just discussed, but these guys loved using the same C2 address.

Early on they used the domain meroo.no-ip.org, which pointed to 216.6.0.28, which I mentioned because it was actually outed in the CNN article in February. But despite this and the shutdown of their domain, they continued to distribute malware which connected to this address for months.

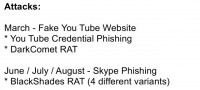

So, they were responsible for the campaigns I mentioned earlier (see right-hand image), involving the fake revolutionary documents, the fake Skype encryption, applications, the Zero-Hour plan for Aleppo, and many more.

Syria isn’t the only country in this region that has experienced these types of operations though. After the success of the revolution in Tunisia, protests on living conditions began in November in Libya: protesters clashed with the police and government officers, and most people know what happened next.

The information I’m giving today is from analysis I did for forthcoming case study. During the uprising it was alleged that someone had located Gaddafi’s hiding place and located it on Google Earth (see left-hand image). Having these files suddenly become something that was appealing to many, many people.

One of the not completely understood adversaries of the Lybian opposition figured this out and created an allegedly self-extracting file with these types of data. This malware was targeted at the Libyan opposition fighters using Skype accounts of compromised friends. This particular piece of malware was used to compromise a computer located in one of the key military operations, where decisions were being made about targeting and military strategy. This malware acted as a keylogger, and the same C2 domain was used.

So, Bahrain; protests in Bahrain started on 14th of February and were initially aimed at achieving greater political freedom and respect for human rights. Unrest continues to the present day, there’s been imprisonment of human rights campaigners. In addition to this, without drawing any correlation, there has been an information operation involving more advanced malware than any I’ve discussed today so far.

In a campaign discovered in April of this year, malware was sent to activists via emails, extensively from reputable figures containing political content pertaining to the uprising. The samples I’ve seen are masqueraded as images or .doc files, and when they’re opened, they display a picture that the user has expected. However, they also perform additional operations.

They install a multi-featured piece of surveillance malware which allows for the harvesting and exfiltration of many different types of data, including screenshots, key strokes, Skype calls, and more. It utilizes a virtualized packer to avoid identification and analysis. It contains many tricks to crash debuggers and bypass anti-virus software.

Data is exfiltrated to an address in the range owned by Batelco, Bahrain’s main state-owned telecommunications company. While the malware contained many techniques to frustrate dissection, persistence revealed this. In the memory space of the infected process, what appeared to be debugged strings featuring the word “finspy” were discovered (see right-hand image).

According to documents leaked by WikiLeaks, Finspy is allegedly part of an intrusion monitoring kit called FinFisher. This toolkit came to public attention after the Egyptian revolution, when documents of the state security apparatus (see left-hand image) were scrutinized. These documents seem to suggest that the Egyptian government had been involved in the discussion over the purchase of this software.

Because it’s a turbo talk, I don’t have time to go into all the details of this malware or the investigations surrounding it. However, this research has been summarized in a blog post which you can read at this link: https://citizenlab.ca/2012/07/from-bahrain-with-love-finfishers-spy-kit-exposed/.

So, what can we actually do about all of this? Letting people know that there’s stuff going on is really important, which is why I have blog posts on the people that they’ve targeted (see right-hand image). They can do smarter things. If people in general know what’s going on, they can be better educated. Also there is a theory that if you know there’s stuff going on, you can come to the Black Hat, to the security community, and give a talk about it, so people that are smarter than you, well, smarter than me, will think about these problems and come up with creative and novel solutions.

So, thank you! Questions?

Question: Were these tools off-the-shelf copies of the RATs or were they custom modified for this purpose?

Morgan Marquis-Boire: Some of these require purchase, and I haven’t actually purchased them, so I can’t comment on whether or not. Anyone else? Otherwise we’ll be on good time for the next turbo talks. Great, thank you!