The increasingly disturbing issue of the cyberbullying phenomenon getting discussed and analyzed by InfoSec professionals David Kirkpatrick, Sameer Hinduja, Joe Sullivan, Jaana Juvonen and Mark Krause during RSA Conference US keynote.

David Kirkpatrick: Welcome back from lunch and I’m told that you’re a very good audience, so I hope you will prove that in the coming 45 minutes. RSA has put together a superb session which I’m about to moderate, so could the panelists please join me onstage.

David Kirkpatrick: Welcome back from lunch and I’m told that you’re a very good audience, so I hope you will prove that in the coming 45 minutes. RSA has put together a superb session which I’m about to moderate, so could the panelists please join me onstage.

So, let me just quickly introduce these excellent panelists. We’re going to have what I think you’ll find to be a very interesting conversation.

Sameer Hinduja next to me is a professor at Florida Atlantic University – I didn’t bring your bio up. He runs a national cyberbullying centre, which is very influential and has done a lot of really excellent work.

Mark Krause is a lawyer who was formerly a federal prosecutor and is particularly pertinent for this discussion, because I’m sure many of you heard the story of the woman who taunted a friend of her daughter’s on Myspace a few years ago, and the friend ended up killing herself, and the mother of the friend who taunted the girl was prosecuted by Mark. Mark is now a lawyer at Warner Bros.

Next to Mark is Joe Sullivan, who is Head of Security at Facebook, which makes him an especially valuable panelist and we’re really happy to have him, and close to my heart, since my book is off the screen, but I spent a lot of time and still spend a lot of time thinking about Facebook.

Finally, Jaana Juvonen; Jaana is a professor at UCLA and a real expert in bullying, who’s really spent many years studying bullying offline and has now become an expert in online bullying as well.

So, just quickly, this session is sort of a follow-up to a session some of you may have seen 6 years ago in this very room on this stage at this conference, which was sort of an early effort to look at this question of: “What are the dangers of cyber space for children?” And at the time, the primary danger was perceived to be sexual predators, and that was the main thing we discussed.

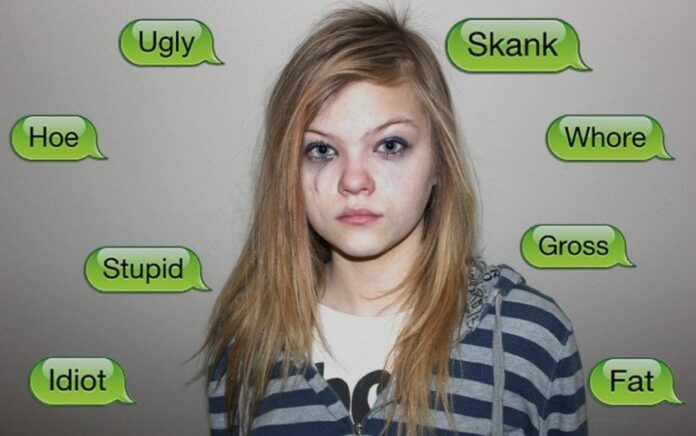

It was pretty alarming, and there was a lot of interesting information, and I went and wrote an article about it afterwards at Fortune, where I currently worked at the time. But in the interim a lot has changed, and while sexual predators online remain a genuine concern, one of the things that has become quite apparent is that for all of the fears and concerns about that, the dangers there and the incident rate there is relatively small compared to a much greater set of risks and problems for young people, which is cyberbullying. And that’s the main thing we’re going to talk about today.

The thing about bullying and cyberbullying, as you’ll hear from the panelists, is that it does have real consequences. It’s a tremendous source of pain for young people. A lot of recent studies have found, documented the serious emotional damage that adults have when they’ve been bullied in childhood, and also when they were bullies in childhood, which is interesting.

And another interesting thing that I learned in preparing for this panel, which I didn’t know, is the significant percentage of bullies who are themselves bullied, and there’s sort of a lot of overlap there.

But a big thing that has changed since 2007, when I was up here moderating that last panel, is that at that time Myspace was still the dominant social network, and a lot of the discussion was about Myspace. Myspace, as you know, has essentially gone away as a social network. In the meantime Facebook has become the overwhelming centre of young people’s online activity.

And that has brought about another very significant change, because Facebook is an identity-based environment; therefore it isn’t as easy to hide who you are when you’re doing anything not so good on the Internet as it was before. So this identity-based nature of Facebook and the fact that people use their real name is a big deal.

One of the things also that is really a big part of today’s online landscape is that photography and pictures are a big part of the way that people bully each other when they’re teenagers or younger. And how you deal with that is something you’re going to hear a fair amount about on this panel.

Another final point, though, is that one of the things that makes this whole area so fraught, as I’m sure any of you who are parents and probably most of you realize, is that the kids in general are ahead of the adults on all this stuff, so no matter how aware we become and how careful and thoughtful we are in our efforts, they’re adopting new technologies when we’re figuring out the strategies for the old ones.

My own personal belief, and I don’t know how much we’ll discuss it on the panel, but the school system in general, all over the country, and, to some larger extent, the world, really has not gotten their arms around the degree to which children live in a digital environment.

And education per se, as it’s practiced broadly, is not educating our children nearly enough about the world in which they already live, which is a digitally infused one. So among the many things that schools don’t do – is do enough to teach kids about cyberbullying and a lot of associated things, like empathy, which is a whole another matter, but we’ll hear about that.

So, maybe, since I’ve just mentioned empathy, and it really isn’t a technical question, I guess I will start with empathy. Let me start with asking you, Sameer: you know, people presume, and a lot of articles say that we are in an epidemic of online bullying. Is that the way you see it? And how bad is the problem of cyberbullying for young people?

Sameer Hinduja: So, in the media there’s definitely been a lot of focus on this specific issue, primarily stemming from the fact that we’ve had some massive tragedies: you think about the suicide, you think about, again, the emotional and psychological damage that is occurring to teens following being bullied. And so everyone thinks that it is this epidemic, that it is spiraling out of control.

But when we look at the research, what we find is that the numbers are small, not incredibly small, but it’s a minority of students, a minority of youth. We find that it’s about 1 out of 4, 1 out of 5 of those who are 17 years of age and younger have been cyber bullied over the course of their lifetime. So, 20-25%, and when it comes to offending or being an online bully, it’s about 15 to 20% – so again, not spiraling out of control, but still a meaningful proportion of youth that definitely warrants us to address.

David Kirkpatrick: But I think you told me on the phone that the press is always calling you trying to get you to say that it’s getting worse. It’s not that it isn’t bad, though, right?

Sameer Hinduja: Right, and they’re also always looking for a direct link between, let’s say, bullying and cyberbullying and suicide. When we think of suicide, in fact, in the specific case studies, of course, there are horrific stories, but almost all of those youths have had something else going on in the background, such as dealing with psychosomatic illnesses, dealing with depression, being on psychotropic medication, so life is complicated.

We remember what it was like being an adolescent; we care so much about peers and their perceptions of us. We want to belong, we want to be popular, we want to fit in, plus, we’ve got other sorts of stresses related to our identity and our family situation, so this is a constellation of forces that affects our upbringing and affects how we deal with some of these problems in our lives.

David Kirkpatrick: So, Jaana, I want to jump to the other end of the road here. As a social scientist who’s spent your career studying bullying in general, talk a little bit about how online bullying relates to offline bullying, and what you’ve learned about the whole phenomenon.

Jaana Juvonen: You know, it’s interesting, because on the one hand there are more similarities than differences, and there are big overlaps. So, the number one predictor for a kid getting repeatedly cyber bullied is that the kid is bullied at school. So the same kids get bullied, and the same kids, in all likelihood, are also doing the bullying, whether we are talking about the school context and face-to-face, or the electronic world.

At the same time there are pieces of evidence regarding other related questions that make me pause, and this is what I worry about: that the electronic world intensifies and amplifies many of the developmental processes that we are concerned about as parents and teachers and adults in general.

For example, think about your teenagers. What do they like to do? They are always comparing themselves to other people to figure out how attractive they are, how smart they are, how popular they are. Put it now in the context of Facebook, and what you have is access to these 200 to 400 friends, so-called friends, and now you are comparing yourself to these extremely polished, very well packaged images.

So the social comparison process never was easy: we always find somebody who is more attractive and more popular. But now in the context of something like Facebook you are just amplifying the process. The kids are more likely to feel miserable about themselves.

Now take it to the bullying context: what I’m afraid of is that this sense of connectedness that kids have, for example, through Facebook – which is great on one hand – when they experience the cyberbullying, they are so alone. That is, they are in front of their screens, whether it’s the cell phone or a computer screen. And so you have this contrast between, on the one hand, feeling so connected, and at the same time being so very alone.

And we know, based on research, that cyberbullying in terms of how kids perpetrate this nasty spreading of rumors, spreading pictures, etc, it’s easy to do, and at the same time, in all likelihood, over time is a harder experience for kids.

David Kirkpatrick: Do you agree with Sameer that it’s not fundamentally getting worse, even though it’s obviously a subject of serious concern?

Jaana Juvonen: You know, I think I have maybe a slightly different view on it. So, we’ve been doing this research, like you said, in schools for about 20 years now. And what’s really interesting about it is that when we started, bullying still was very overt: kids were calling one another names; they were physically attacking one another – it was visible.

When you put an anti-bullying program in a school, what happens? It goes underground, it goes, and it’s much more covert. And when kids move to the online environment, where so many of their interactions and relationships are now formed and maintained through the electronic communication, it would not be surprising to me at all if over the next few years we’ll see more cyberbullying, and maybe, on balance, less bullying face-to-face.

David Kirkpatrick: Mark, talk just a little bit about the Megan Meier case, which you did prosecuting, to summarize what happened there and give a view, from a law enforcement perspective, what you think can be done and how law enforcement is to be viewed in relation to this issue?

Mark Krause: Sure; for those of you who may or may not be familiar with the case, Megan Meier was a teenage girl in the St. Louis area. She was friends with another girl about her age. Megan’s parents decided to move her to a different school, and as a consequence her relationship with the other girl became more strained.

The parents of that other girl were hurt by this, in particular the mother. And so the mother, her daughter, and the nanny/employee of the mother concocted this plan where they were going to teach Megan a lesson. They created a fake profile of a very handsome shirtless man, well, teenage boy, who befriended and then romanced Megan online. After this went on for a while, Megan fell hard for the guy, the catfish, as it were. And ultimately, as per the plan, they humiliated her, teased her online, and it got so bad one night they said: “You should eat shit and die,” if you’d excuse my language. And I think then at that point she went upstairs and hung herself.

David Kirkpatrick: What year was that?

Mark Krause: That would have been in 2007, I believe. The local DA in the St. Louis area, the St. Charles region did not think this was necessarily a criminal case and quite publicly said: “Look, this is not a crime, nothing to see here.” Because the communications on Myspace got routed through Los Angeles, our office had jurisdiction over the case, and the mother was indicted under a cyber crime statute. She proceeded to trial and was convicted of a misdemeanor offence, which the judge then vacated, so she was acquitted.

David Kirkpatrick: Having been so deeply involved in that, and given this transition I described before, where Facebook has now become the central place where kids interact online, do you think it would be less likely for that kind of thing to happen today because of the identity-based nature of Facebook?

Mark Krause: You know, it’s hard to say. I mean, I think that there’s going to be people who are going to seek to do other people ill, regardless of the form. There are going to be some people out there who are going to engage in antisocial conduct, regardless of the mechanism. Certainly, the anonymity of Myspace helped these perpetrators, at least in my view. But I think that there will be bullying as long as there is communication.

David Kirkpatrick: So, what was the kind of conclusion you drew at the end of this whole experience about what law enforcement can and can’t do?

Mark Krause: Well, it’s certainly not a problem that I think you can arrest your way out of. There are not enough resources, because a lot of this is juvenile on juvenile. There are a number of obstacles to bring a criminal case against juveniles. I think that law enforcement can play a role, go for more extreme cases, as we did in this particular case, go against an adult on adult conduct, or, in this case, adult on juvenile conduct. But I think you cannot look to law enforcement the way that you’re going to solve the problem.

David Kirkpatrick: Ok, so, Joe, what is Facebook’s general perspective on this? I mean, you, I know, think about it a lot. So how should we view Facebook in the context of this problem and what should we expect from Facebook?

Joe Sullivan: I think the way we view it is a lot like this panel: we’re probably talking twice as much to the academics as we are to law enforcement right now when it comes to dealing with this issue. And then the only thing missing from this stage would be a teacher and a parent in terms of the dialogue that we’re trying to have.

David Kirkpatrick: I think we have a lot of parents here.

Joe Sullivan: Come on up. So, a lot has changed since your panel in 2007 in terms of sites like Facebook trying to deal with the challenges in this area. I think in 2007 Internet sites viewed their obligations as: have a report button on the site, and then have a warehouse full of employees reviewing each of those reports. And we all start there, and Facebook started there.

But what you quickly realize when you start reviewing reports from 13- and 14-year-olds about being bullied is that it’s really hard for a third party to look at that situation and make a judgment call. Point #1: it’s really hard to make that judgment call; and then point #2: it’s very hard for that 13-year-old to press a button that says: “Report violation of terms”.

And so, what we’ve needed to do is get a lot more sophisticated over time. And so we started out testing a lot of different things, and I think what we’re doing now is very different from what we were doing even 2 or 3 years ago.

We came up with this concept of social reporting, with the idea there being that, if you feel that you’re being targeted, it might be better for you to reach out to a member of your community, a trusted member of the community who could help you with the situation, and not feel so alone.

I was at the anti-bullying conference, and one of the people speaking said: “The most important thing for preventing bullying is to make sure that the potential target knows before they’re bullied that they have someone they can turn to for help”. So, the social reporting is built on the idea that if you have someone that you can turn to, let’s make it really easy.

And so, if you see a photo of yourself on Facebook that you think is inappropriate and attacking you, you can select that report option, but now there are multiple avenues that you can go. First we added this idea of reporting it to a third party who can help you. And then more recently we added: “Why not reach out to the person who posted it?” And that’s what we’ve been studying over the last couple of years.

One of our senior engineers got really interested in this idea of compassion research and started working with some academics at a couple of institutions of higher education. And we’ve learned so much just in a couple of years. I think the first thing we’ve learned is that we have a long way to go. But we’ve also learned that how you characterize what’s going on matters tremendously.

So, a 13-year-old would be happy to press a button that says: “Send this message to the other 13-year-old” saying: “Please remove that photo; it makes me embarrassed.” But they don’t want to press a button that says: “I think you’re violating Facebook’s Terms of Service”.

David Kirkpatrick: We’re going to come back to this in a little while.

Joe Sullivan: So I think there is a lot we can learn about how we communicate about this concept of bullying, and there is a lot we can do to empower the person who’s targeted to have a voice, and that’s the direction we want to go as a platform.

David Kirkpatrick: On that work, which we’re going to talk about more that you’re referring to, you’re working with a lot of very serious academics at Yale and elsewhere. Could you talk just a little bit about how much you’re interacting with outside professionals on this?

Joe Sullivan: Sure. I mentioned one of our senior engineering directors reached out to some academics who were doing compassion research, and essentially asked them to help us redesign the flows on our site. So we had a public workshop a few weeks ago, where they unveiled the second round of research, so, specifically looking at 13- and 14-year-olds in the United States and presenting different reporting flows to these teenagers.

Because of the volume of 300 million photographs being uploaded to Facebook on a typical day, even if a tiny percentage of those result in someone feeling awkward and embarrassed or targeted and they report, that’s a lot of report flows that we can surface and study the results of how changing one word can impact.

And then what else can we put into those flows to help address the situation? You used the word ‘empathy’, which is, I think, a really important word here. What we found is that most of the time the person who put up their photo didn’t have empathy for the person who felt targeted. And so the question is: “Can we build empathy in the context of them working through it?” So in some of the flows we’ll actually surface things that the two of you have in common.

David Kirkpatrick: I want to ask other panelists too about this issue of empathy, because I think almost everyone of you mentioned it as we were prepping for this. And I noticed you sounded like you might have a thought about some of the things Joe was saying. How do we think about empathy and how it relates to this whole problem generally? How do you look at it?

Sameer Hinduja: Well, given the right circumstances, having a crappy day, maybe we’re struggling with some sort of stresses in our family – we could be mean, we could be cruel, we could be vicious to somebody else, and, just like Joe mentioned, what happens is that you’re presented with an opportunity to harass or intimidate or threaten or embarrass somebody else, and so, at that very moment do you really allow your morals or consciousness or anything else to sort of guide your behavior? Probably not; you typically just fly off the handle, respond spontaneously, respond based on emotions, and you go off on another person, and that’s where the harm occurs.

And so, I believe that empathy is so huge because, again, if we come alongside these teens, if we say: “Look, I’m your biggest fan. I believe in you, I want to support you, but the behavior is the problem,” the behavior’s got to go. So how can we implicate their consciousness? How can we implicate their hearts at that very moment before they go ahead and send it?

And hopefully, that will lead some solutions, because pause before we post, like we like to say, and they’ll think: “Oh, wait, this is going to lead to some sort of harm.” It’s not just something we can relegate to cyber space, where it doesn’t have real-world ramifications – it definitely affects the other person: “I wouldn’t want them ever sending something similar to me.” So yeah, if we get them to pause and think about it, hopefully empathy will be informed and they won’t go ahead and send that message or post that photo.

David Kirkpatrick: And Jaana, you’ve actually studied this?

Jaana Juvonen: Yeah. So, again, I think that that’s a really great goal, and I think that’s another really good example about how the electronic communication form amplifies these things; that it is far too easy to send a message that is nasty, or at least not kind and considerate.

But there is a distinction between chronic bullies and then there are kids who do it without really realizing. But they’re not really the ongoing persistent bullies, so to speak. And I think that the empathy might work for those who do it inadvertently and didn’t really mean that well.

But for the hardcore bullies, what we know about them: they lack empathy, so far we’ve not been able to teach them empathy; they really don’t care about other people’s feelings, but they enjoy a distress reaction. And obviously, this now depicts a very different kind of view of, thank goodness, a small proportion of kids at any one time.

But what can we do there? If we can’t teach the hardcore bullies about empathy, we can teach the bystanders about empathy. And that’s, I think, one of the totally unused, uncapitalized aspects of whatever electronic communication that we are talking about. That is, in real world how this works is that all kids essentially say: “Bullying is wrong, it should not be tolerated.”

When you see how kids react to bullying, nobody intervenes; very rare that anybody would be gutsy enough to go and try to intervene. However, when it happens, bullying stops within seconds. When one person says: “Hey, stop that, that’s not ok,” a peer would be really powerful, but why don’t kids do that? They don’t do it because that puts them at risk, right? So I’m not going to risk myself and get in between this powerful bully, because they typically are popular, they have a lot of status, they know exactly how to hurt other people, which is typical in bullying situations, that is, the more powerful the one is abusing his or her power to put down the vulnerable one.

If we now offset this imbalance of power by telling kids: “Hey, do it together. So you can stick up to the bully if you stick together. So if you combine your forces, you’re going to be much more powerful than any one kid.” And I think that the online environment is an absolutely fascinating place to try to teach kids about empathy and the role that they play as bystanders there, because the bully does not, in their case, know that they did not forward that nasty picture. So they could stop and not spread that nasty rumor.

Sameer Hinduja: I feel like definitely there’s concern about being labeled a tattletale, and so they hesitate. But I also feel like, you know, we work with tens of thousands of youths, they also say: “We just don’t know what to do.”

And so, my hope is that we can build into the workflow and the communication methods, industry can help with that as well, that right when they’re about to, they’re brought to think about the issue, they’re brought to consider: “Ok, what are the consequences?” and so forth. They know: “It’s not just ok. Should I talk to an adult? Should I go ahead and press the Report button on the site? Should I contact my cellular service provider to block this specific number?” They need to have on-hand various sort of assortment of options they can then pursue. Some of them are technical, some of them are more social and behavioral.

David Kirkpatrick: Mark, this issue of the bystanders played a big role in the hours leading up to Megan Meier’s suicide, right?

Mark Krause: I think that that’s probably right. While the defendant and her daughter and her employee were sending the nasty messages to Meier, there were some other people who were involved in the communication. They were sort of the masses that she was dealing with at that time. So, it undoubtedly led to her feelings of isolation and being ostracized that the masses were also against her.

David Kirkpatrick: I assume nobody spoke up and said: “Wait a minute…”

Mark Krause: No.

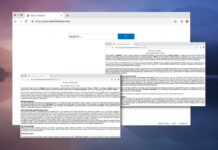

David Kirkpatrick: So, I want to switch gears a little bit and show you guys something as a way of leading to my next questions for Joe. So, could we have the slides please? What Joe was referring to in the beginning about some of the work Facebook’s been doing, we can show you. And this has not been shown much in public. So, maybe you could just quickly talk us through, Joe, and I want to as quickly as we can, but what are we looking at here?

Joe Sullivan: So, say, I was on the site and I saw the photo that’s on the left there, and I thought that it was targeting me. And I chose to report (see right-hand image).

David Kirkpatrick: It’s not a very good example of the photo.

Joe Sullivan: It could be a picture of somebody wearing something. Maybe it’s a picture of me, and there is a comment where they’re talking about the length of my pants, or something like that. You can see the choices; there’s no choice there that says: “It’s a violation of the terms,” or “It’s my intellectual property,” something we put at the bottom, because we get intellectual property reports as well, but that’s kind of a separate flow. And then, what we see most of the time with the 13- and 14-year-olds is that they don’t like the photo because it’s embarrassing. They choose that almost every time.

David Kirkpatrick: But they can choose any of these.

Joe Sullivan: Right, and so they can choose one of these, and you can see the terminology – when we tested, this is the type of terminology that worked for 13- and 14-year-olds. You can see there is a message box (see right-hand image). We tested putting nothing in the box, and then we tested lots of different language, and what we found was: if we prepopulate the box, it does much better in terms of someone’s comfort to send. If they’re faced with that empty box, it’s really hard to write. And if you write, you might say something harsh, which might not be well received. So we’re measuring both from the sender and the recipient.

And then you see we put in the word “please”. The exact same text without the word “please” in it does not do nearly as well. So we add the word “please” and it performs substantially better both from the sender’s willingness to send it and recipient’s willingness to then remove the photo.

So that was kind of like the sending side. Now, this person is the person who posted a photo, and so they received this message and it says, they actually see the message that says: “Please take down the photo – I don’t want people to see it, would you take it down?” (see image above) No judgment there, so then you have the options: “What do you want to do? I want to remove it, change the privacy, or keep it as it is.” (right-hand image)

David Kirkpatrick: So you always force them to see this dialogue box if the recipient is going through the other stuff?

Joe Sullivan: Right, so you got to make a decision now. I mean, you could click and exit the page, but if you stay on Facebook, you’re going to get to this point. And so you’re going to make a decision to leave it up.

David Kirkpatrick: Now, you’ve had quite extraordinary success with this phase of it, right?

Joe Sullivan: Right. I can’t remember the exact number, but a dramatic percentage of the time, so, more than 50% of the time the person who received the message is going to remove the photo.

David Kirkpatrick: More than half of the time – that is a huge progress. And then, what do we have here?

Joe Sullivan: And then, after they’ve removed the photo, we actually encouraged them to send back to the person who reported to them a message saying: “Thanks” (see right-hand image). And then the other amazing statistic is the person who removed the photo actually comes out of this feeling positive about the experience.

David Kirkpatrick: You’ve studied that?

Joe Sullivan: Right, no one likes it if Facebook removes their photo. They come out of that experience 100% of the time feeling angry at Facebook. And no one likes it when someone else reports them. And no one likes it when someone else tells them that you’re violating the rules. But could we design a flow that made people feel comfortable removing the photo a large percentage of the time and actually feel good about the experience?

David Kirkpatrick: That is pretty amazing stuff. I’ve got to really say I’m very impressed with that.

Jaana Juvonen: So, I’m curious: when you designed this, did you have data that this was happening automatically between some kids, for example, between friends?

Joe Sullivan: We don’t have that data. The people who are typically in these situations are people who are Facebook friends. And so, there is an assumption that they are communicating on Facebook already. I wish I knew who in or outside the company first came up with the idea that rather than us deal with it, we should try and help people communicate.

Jaana Juvonen: Because what you are now doing is like going back to the empathy, so this might be one of the roles that you play. You are now making something that should be given in any good friendship, right? So if a friend asks you to take a picture down, first of all, it’s a nice request, and then you reply to it, you know you listen to them and you send them something back. So you are basically modeling something that should take place in good relationship contexts.

So, again, I think that it’s a nice thing to have; the question is when you say that maybe this is effective in about 50% of the cases, and don’t take me wrong, I think it’s fantastic; at the same time, what happens in cases where it doesn’t happen, or maybe when it escalates?

Joe Sullivan: I think what this shows us is that we have a long way to go, but that we’re headed in the right direction. We have other things that we try and do in situations where the photo doesn’t get removed. Chances are that photo is going to be reviewed by us, so we still have a lot of people reviewing a lot of photos.

So we’re going to be reviewing those photos, and what we used to do is that if a person was repeatedly using our product for purposes of some type of abuse like that, we would take away their account. Now we’re more likely to put them in a penalty box, if you will. So they basically can’t use Facebook to send messages or post photos for X period of time. I think it’s been mentioned in a number of stories, teenagers will respond that: “Would you rather be grounded for a week or have your Facebook privileges taken away for a week?” So we do have that lever.

But then there’s also this social reporting context, where there are times when parents do need to get involved in helping their teenagers work out their issues; there are times when teachers need to get involved, there are times when some other adult needs to get involved, and so that’s where we’ve created this mechanism: if you see a situation where you’ve been targeted, you don’t have to figure out: “How do I do a screenshot in my browser and how do I save that and then attach it to an email?” It’s actually you can report it out to a third party right in the flow.

Sameer Hinduja: I think it’s also important to mention that definitely this is dealing with pictures, and it’s a leap forward, for sure, and I love to see that. You think about SMS messaging or tweets and so you wonder what can be done on, let’s say, a site level, but also maybe on device level, maybe OS level, maybe mobile OS level, maybe a third party app level in order to, perhaps, create empathy; when individuals might be saying something and you wonder if it could be just built on some sort of corpus or dictionary of hate-based keywords, and whether that could be tied into some sort of predictive algorithm with contextual clues based on other texts. That might, again, signal some sort of warning: “Ok, this is nasty or harmful. Do you really want to send this?”

Again, I don’t have the answers to this, but I really want us as an industry to be thinking about those sorts of questions, because we care about not just profit making, but also clients and customers and stakeholders.

David Kirkpatrick: You know, this is a room full of people whose business is solving problems that happen online, basically. It is very interesting, and I think it’s a fascinating question, whether technology can be employed to try to – I know there’s definitely a lot of people thinking about it and non-profits and others working on projects about this – to help kids learn. They have empathy and they have a very hard time even knowing the degree to which they’re inflicting pain on others. Anybody who wants to comment on anything?

Jaana Juvonen: Well, again, I would make a distinction: there are kids who do these bad things because they don’t think, it just happens, and they do it occasionally. And then there are more than hardcore bullies, who are very cognizant of how they are causing harm.

Sameer Hinduja: That’s a smaller proportion. So, again, we’re thinking about the big picture, we’re thinking about the critical masses, which are those who do it and they weren’t thinking. They’re very harmful, they get caught up in the digital drama, they want to protect their reputation, and so they go off on somebody else.

David Kirkpatrick: Let’s talk more about technologies. We don’t have tons of time remaining, but I’m sure there are people in the audience, perhaps quite a few of them, who have done work on products intended for parents to monitor their kids, and such things. What do you guys think, for example, about these products that allow parents to basically spy on their kids? I’d like each of you to just briefly say what you think about that.

Sameer Hinduja: I feel like my panel will share my perspective. I’m not a parent, so please, be gracious towards me. I feel like when we’re trying to raise kids, we’re trying to, over the course of time, build this candid, open, trustful relationship with them. And I feel like the quickest way to violate that trust is to go and surreptitiously install some sort of, again, third party app on their smartphone or software on their laptop, which could be a keystroke logger, could be monitoring their behavior in social networking sites or chat rooms and so forth.

And I feel like, again, what’s more important, rather than this reactive measure of software is, again, education, and having communication with our kids – much as the stuff that we learned in Parenting 101, I’m told, applies to cyber space; we’ve just got to tweak it a little bit. I feel like this addresses the fundamental problems, because it is a technology problem, but sometimes it’s not as well, because it’s peer conflict issues, it’s how to deal with relational struggle, all these other elements that come together that then lead to online issues.

David Kirkpatrick: Mark, what about you?

Mark Krause: I don’t have a problem with a tool; I think the problem with the issue is how you use it. If there’s no engagement, if parents are relying that at the end all be all without really understanding what’s going on, understanding their child’s role in these relationships, then they’re going to be in for a trouble.

David Kirkpatrick: Joe?

Joe Sullivan: I think that you can’t lump all youth in one category. When you’re looking at what are the solutions, there are different solutions for different ages. And so, as a parent of a 10-year-old, I imagine I will think very differently about how I engage with her when she’s 15, and the things that I can do to oversee her behavior will vary dramatically in years.

And so I don’t think there is a single product out there that works for every situation, and I don’t think it’s good to sell parents on the idea that if you buy X and then install it, your problems are solved. We need a lot more parental education about technology. I think that the best thing parents can do is use the products that their kids are using and find ways to have communication with them about it.

David Kirkpatrick: We just talk about not even becoming their friend on Facebook necessarily, but just being able to talk about the existence of it and how it works.

Joe Sullivan: I’ve seen a great number of examples of the most effective parent approach to get their teen to open up about Facebook was the parent who asks their teen to teach them how to use Facebook. And by asking the teen and making the teen feel like they’re the leader, they were the one who were comfortable saying: “No, here is how your privacy settings work; here is how I hide from you, what I share with the rest of my friends.” And by changing the dynamic and recognizing it, like you said earlier on, I think that the teen knows a lot more about technology sometimes than the parent.

David Kirkpatrick: Jaana, what do you think?

Jaana Juvonen: Absolutely. So, parent education: you can’t protect your kids if you don’t know how it works. Prevention is much more effective than any reactive strategy – absolutely, so what does this mean in the context of cyber behavior? I think it’s not unlike: all the sensitive topics that we have hard time talking to our kids about – drugs, sex; you should not have one talk. You need to bring this up repeatedly, you need to ask what’s going on, you need to try the technology yourself. And that gives you those sort of “teachable moments” if you will. So you can then talk about: “Well, if this were to happen to you, what do you do? When you see this happening to somebody else, what do you do?”

So, that parent communication is absolutely critical, and you don’t want to lose that trust. And when you put these spy pieces in, whether it’s on the computer, whether it’s on the cell phone, whatever – I mean, basically, what you are telling your kid is you don’t trust them. And there’s actually a research showing that we think that parental monitoring, typically, for most kids, is a proactive strategy: you know what your kid is doing at any one time; that prevents them from getting into trouble. But there’s also research showing that for some kids it actually works the other way. That is, when the parents are monitoring, it is a sign that they don’t trust their kid.

Mark Krause: Yeah, and don’t fool yourself: they’re just going over to a friend’s house; he’s there – the same thing with drug dealers.

Joe Sullivan: I had this great experience with my daughter. She came home from school one day and she said: “I’m addicted to G-chat”, and I was like: “But you don’t have a G-chat account”, and she said: “Well, we use it at school.” And then I talked to the folks at the school and they said: “You know, that grade level does not have access to the chat products”, and I asked my daughter, and she said: “We use Google Docs for our collaborative projects in class, and if you create a document, the members who have access to the document can chat inside the document.”

The school rule was you can only chat in the document for the topic of the document, so the 4th grade girls had created a document called Random. So you have the 4th grade girls all meeting in the Random.doc, while we all think they’re doing their homework, and there’s no oversight.

David Kirkpatrick: Well, you know, there’s a lot more to say about – you now, I wanted to get into keyword filtering, and you talk about maybe this stuff should be built in OS. I think there’s a lot more work for everyone in this room to do. I want to thank the panel very much; it was, I think, a really interesting conversation, so I appreciate having you here. Just to wrap up: RSA has produced a short video with some ideas about things that can be done. We exit the stage, check out what RSA’s put together to give you a little action idea. So, thanks again to my panelists.